TYPEWRIT ; ERRORS AND COMPOSITION IN THE POETICS OF PLACE

While in Panama on site visit, I wrote a poem for each of the twelve days I was there. This was done with pen in my notebook. In the meantime, I started making a list of as many surface qualities as I could manage; by the end of the site-visit I had 37. Alongside this I shot seven rolls of black and white film trying to capture the various textures and surfaces of Panama and its waters. This was accomplished through daily walks and observations from the coast of Panama City. Given the nature of the analogue photographic process, I could not see the photographs I was making until I had returned to the Netherlands. Further, in order to lift the poems from the notebook into a presentable format, I used my typewriter. Retyping the poems unintentionally allowed for further editing, this was also accomplished in the Netherlands, after being on site. There is therefore in both cases (poem and image) a deferral of the site, a postponement of the encounter with what it seeks to describe. This set out the beginning of thoughts of the image as (non)site, a relationship between site and sightlessness, and the idea that process, form, and content are much more involved with one another than is commonly understood.

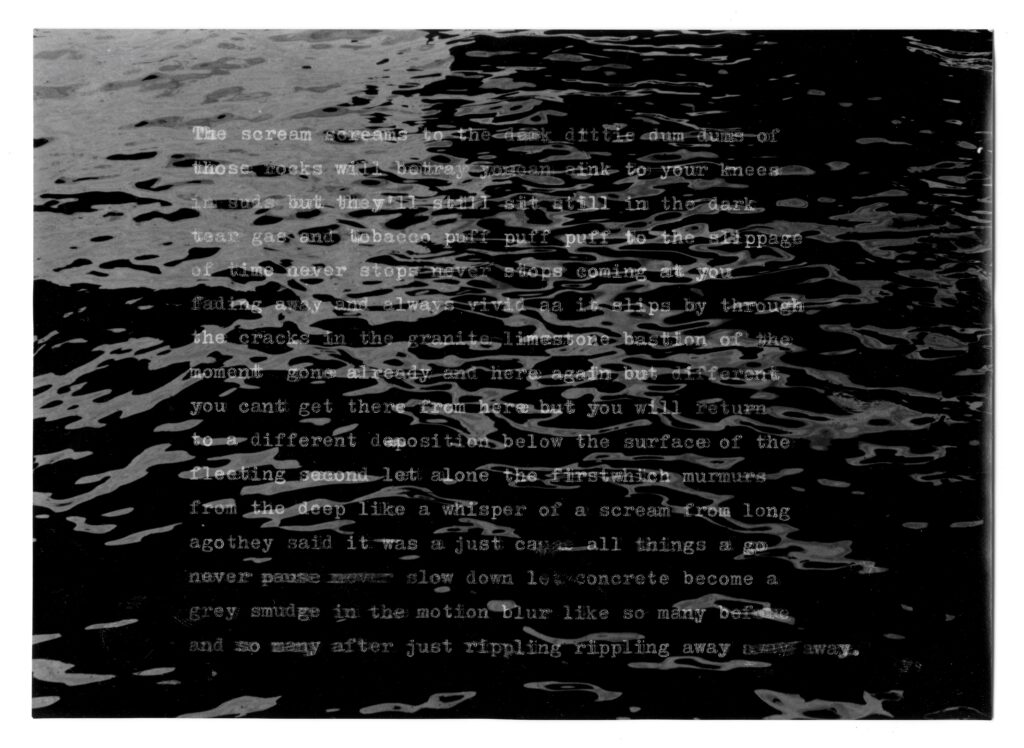

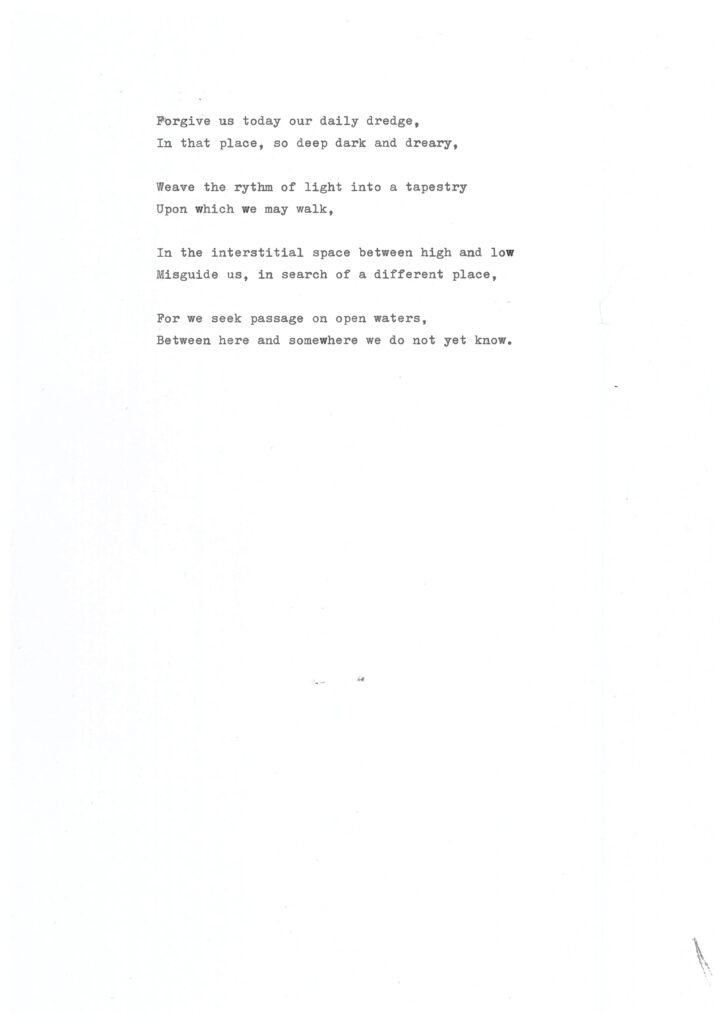

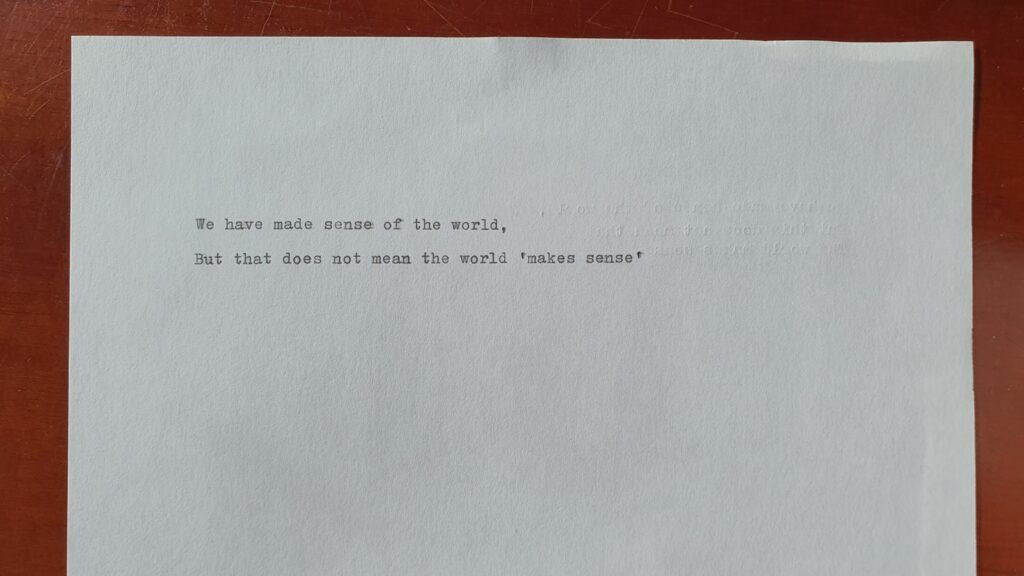

Typewriting is a skill that, unlike using a keyboard in Microsoft Word, requires practice. The results can be unforgiving because there is no backspace, it is real. In typing out these poems, I had created mistakes – transferring poetry from a handwritten notebook to A4 sheets, and editing on the fly while needing to focus much more diligently on each keystroke resulted in mistakes. I tried to correct them in the same document instead of typing them onto a clean sheet of paper; thereby leaving traces of changing ideas, missteps in the production, lapses in judgment and fragments of a contingent poetry. The error gained power as a compositional feature, so long as it was accommodated within the structure and goal of the final product. These poems were titled, ‘Poems on Water’ and bundled as a loose collection of pages, indulging in the ambiguity that the work was at once ‘on’ the topic of water, and at the same time, the ideas were afloat, in motion, and therefore quite literally on water. While at the typewriter, I produced one additional poem, composed of the corrective keystroke of the dash: ‘-‘ to create a sequence of lines and rhythms that emulate the pattern of ripples receding into the distance.

Operations in the Dark

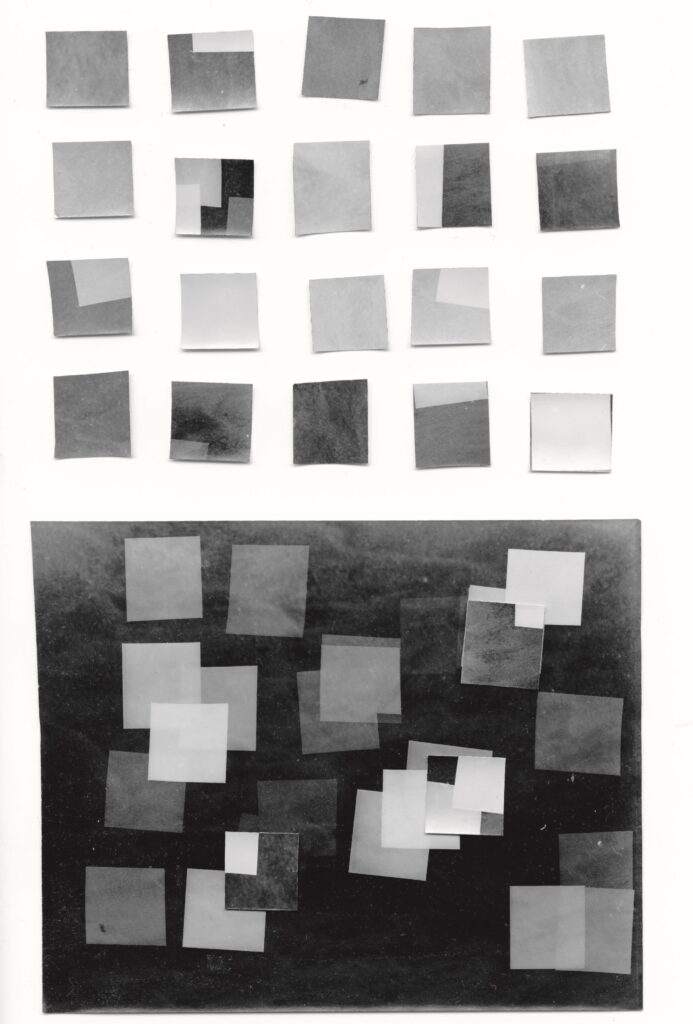

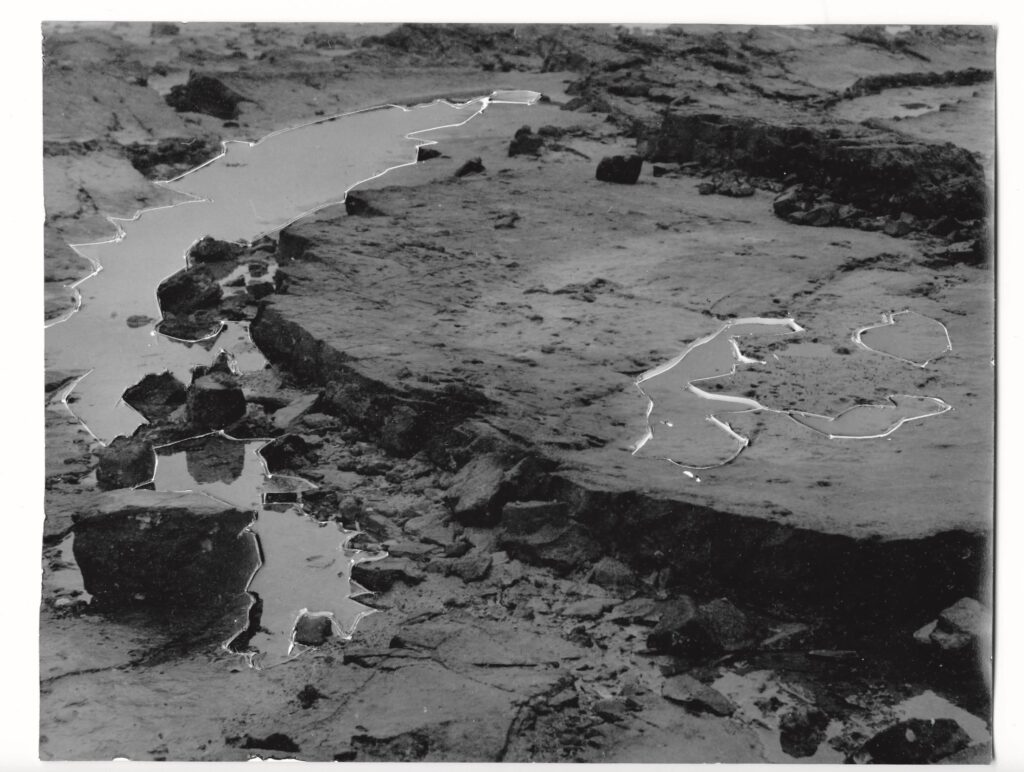

After developing the photographic negatives, the darkroom was used to create prints on silver gelatin photo-sensitive paper. These dark room enlargements were created as a set of photo mappings of the site. A series of operations were carried out in the dark in order to generate new understandings of the site, the image, and their relationship. These photo mappings applied non-conventional print making techniques that necessitated operating on the photo-sensitive paper as a model material before its exposure to the image – this meant working on the paper in the dark, making cuts, rips, and weaves and eventually typing. This enabled a series of errors to emerge, that were consistently more interesting than the actual intention of each work. The error’s compositional strength emerged from a practice that requires incredible control – all light must be eliminated from the room, exposure times are fixed to millisecond increments, photosensitive papers carry different properties that respond differently depending on the negative image itself, developing chemicals are diluted and measured accordingly and held at particular temperature, meanwhile the paper’s exposure to the image is timed and then it goes through a measured procedure of three chemical baths. One sixtieth of a second in Panama at f8 aperture, followed by (in the Netherlands) 9 minutes of developer, rinse, and 5 minutes of fix, and then in the dark again, fifteen point five seconds at f4 aperture and 45cm, three minutes of development, thirty seconds in the stop bath, two minutes of fixer, and the lights come on to reveal an image, or a black piece of paper. As a novice in the darkroom, making mistakes was easy, but too many could cost the work entirely – five hours in the dark room could yield a single image on A6 paper. The minor error, the ‘almost perfect’ emerged as those instances where the truth of the process shone through and yet the control over the system was enough that the intention was clear; of course as a viewer you never know what is accident, and what is compositional choice, and when operating in this logic that line is blurred for the author as well.

As this series progressed it became clear that there was a distance between the image produced and the site it seemed to represent. My experience of Panama is represented by the frame of the photo and the sixteenth of a second that I was physically there. When compared to the five hours spent with that frame in the dark (at home) it is clear that the experience of the image is distinct from my experience of Panama – and yet they are reliant on each other. There is therefore inherent in the analysis an element of fiction – a Panama imagined retroactively and spoken about within the limits of a clinical (photographic) frame. A challenge to the frame in the context of the pacific waters; an idea that the site is a fiction which I can no longer experience; and operations that were carried out in the dark and relied on projection and light; pulled the project further and further from the safety of shore, and out to sea.

In doing so questions emerged that focused on navigation – how to know where one is going when there is a perfectly flat horizon in 360 degree vision, and how to navigate in the dark? It also required an understanding of technologies of boat building and other floating structures, and pertinently, it caused an investigation into the histories of the global measure.

Extensibility and intensity

Operating in the dark brings with it an inherent possibility of the unknown – the possibility to make mistake, or in the case of open-water travel, run aground in shallow reefs or otherwise drift off without even knowing it. The lighthouses of Panama serve to indicate particular locations with particular light signatures – timed intervals of blinking light that distinguish one lighthouse from another – and this system of lights continues throughout the extent of the Panama canal, ensuring boats remain in the deepest parts of the channel.

On the Pacific coast there are seven lighthouses that share a specific light signature with another. This allows for a ship captain to confuse one location with another, to make a mistake. In that moment of confusion, when two lighthouses exist in the same location, the mental model of Panama becomes something completely different; a different shape.

It’s also important to note that the same rigid system of measure is applied to the surface of the ocean along the vertical axis.

Depth measures for centuries have been done in something called Fathoms – and Figure 10 shows a print from 1555, an anthropological study by Olaus Magnus of the Nordic people at the time. We can see two characters retrieving a plumb line from the depths to measure how many fathoms deep the water is; one fathom was the distance of outstretched arms. So it comes to be that waters too deep for the line, unable to be embraced by outstretched arms, were ‘unfathomable’.

Out of these analyzes emerges a relationship between light, position, and topology of the continent which can (dis)place a boat in the captain’s understanding, even if just for a moment. The idea of the datum, or the fixed abstract line in top down or sectional understanding of space is in fact non-existent, however, these datums have become the tools with which we make sense of the world. Further yet, these abstract lines have concretized to such an extent that we are in fact reliant on them in order to function; the abstract measure has replaced the tacit knowledge of depth, orientation, and position. This is a spatial and temporal griding. The project seeks to explore the paradox that is the collision of the hyperlocal experience of site, with the extensible and systemic measure that positions it somewhere .

The project takes shape by looking at this issue not as a singular one, but as something inherently multiple. In other words, it aims to reveal the absurdity of the reductive and systemic measure by subverting the Cartesian logic of the sectional datum lines and the grid of the map.