THE LAND DIVIDED, THE WORLD UNITED

Few territories across the globe hold a strategic importance comparable to that of the Panamanian isthmus. The isthmus – a product of the dynamic geological becomings of the Earth – produces a dialectic tension of connection and disconnection, between landmasses, oceans, climates, ecosystems, cultures, peoples, empires, markets and more. Its geographic position has destined, or doomed, it to become the focal point for assemblies of actants across scales, matter and flows that come together unmatched in their intensity and specificity.

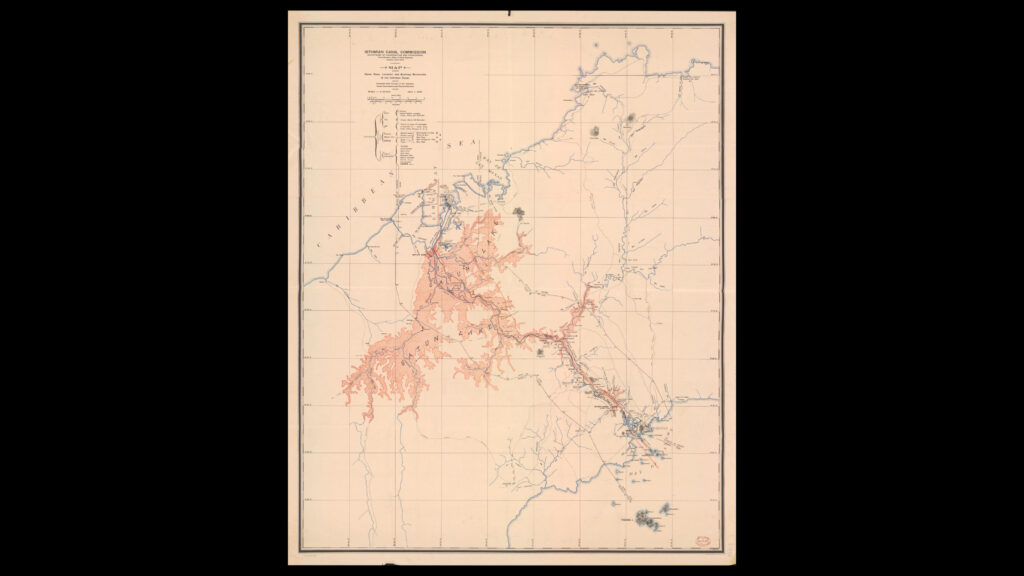

This project focuses on the colonial context of the Panamaian Isthmus and the history of Western intervention, a conscious choice that acknowledges a level of ignorance towards the territory’s rich pre-colonial history. As soon as 1529, 37 years after Columbus’ landing on present-day Hispaniola, the Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa successfully crosses the isthmus, transforming Panamanian territory into the logistical cornerstone of early colonial exploitation of the Americas. Vast quantities of most importantly precious metals from the Andes are hauled over the roughly 60 kilometres wide land bridge on their way to fill the treasuries of the Iberian peninsula, with armies, germs and Christianity crossing it the other way. Despite its terrain being particularly logistically inhospitable, it nevertheless serves as a focal point that enables the rapid intensification of colonial control and extraction; its territory becoming an integral node and choke point of empire.

Losing in significance with the decline of the Spanish, the Panamaian Isthmus quickly re-attains its importance with the rise of the American empire, as the American frontier reaches the Pacific coast. The absence of stable and efficient transport routes prior to the trans-continental railroad in the North, catalysed by the Californian gold rush, puts Panama back into the spotlight of colonial logistics, as settlers and cargo turn south for the easiest way to cross the continent. With the railroad eventually crossing the isthmus in 1850, US-American ambitions of control tighten under military deployment and various agreements with the then-Colombian government in Bogotá. Yet it was only after the failure of the French effort to construct a sea-level canal that the US would fully actualise its control of the isthmus. Having failed to negotiate a deal with the Colombian government on the construction of a Canal and rushing to secure the remaining French assets, the US backs a group of Panamanian rebels in their secession from Colombia with swift military deployment, immediately striking a deal to secure provisions for the construction of the Canal with the new-born nation of Panama.

Apart from laying the foundation of the Panama Canal, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty brings about a special condition of (extra-) territoriality, a rather common occurrence in colonial history, which leaves a lasting legacy on the territory of the isthmus. With the motto The Land Divided, The World United – a scale of ambitions aiming to reverse the very geological forces that created the isthmus in the first place – the Panama Canal Zone becomes a colonial project to secure territories, resources and necessary control for the uninterrupted exploitation of the Panama Canal by the new US administration. With the reliable operation of the Canal as its raison d’être, its implications and spatial outcomes however reach far beyond that, significantly altering territorial logic and relationships on the isthmus, well beyond spatial and temporal confines of its operation.

While the Zone itself is no longer there, its spatial products are still very much present today. Scattered across the isthmus, most curious objects such as antenna arrays, bunkers, forts and airstrips; but also more mundane yet distinct ones such as drainage systems or housing units built to a US standard, shape the territory to this day. While some have already been appropriated and transformed to better serve post-Zonian needs, others exhibit a degree of otherness that prevents their use in the contemporary context. Yet more often than not, since those objects were necessitated by problems of military logistics and communication, they were designed as highly efficient nodes in (extra-)territorial systems and flows. The obvious question that arises is thus, whether the specificity and strategic location of these objects can potentially be put to use for new, post-militaristic purposes, consciously taking advantage of the otherness they inhibit.