SITE AND SITELESSNESS

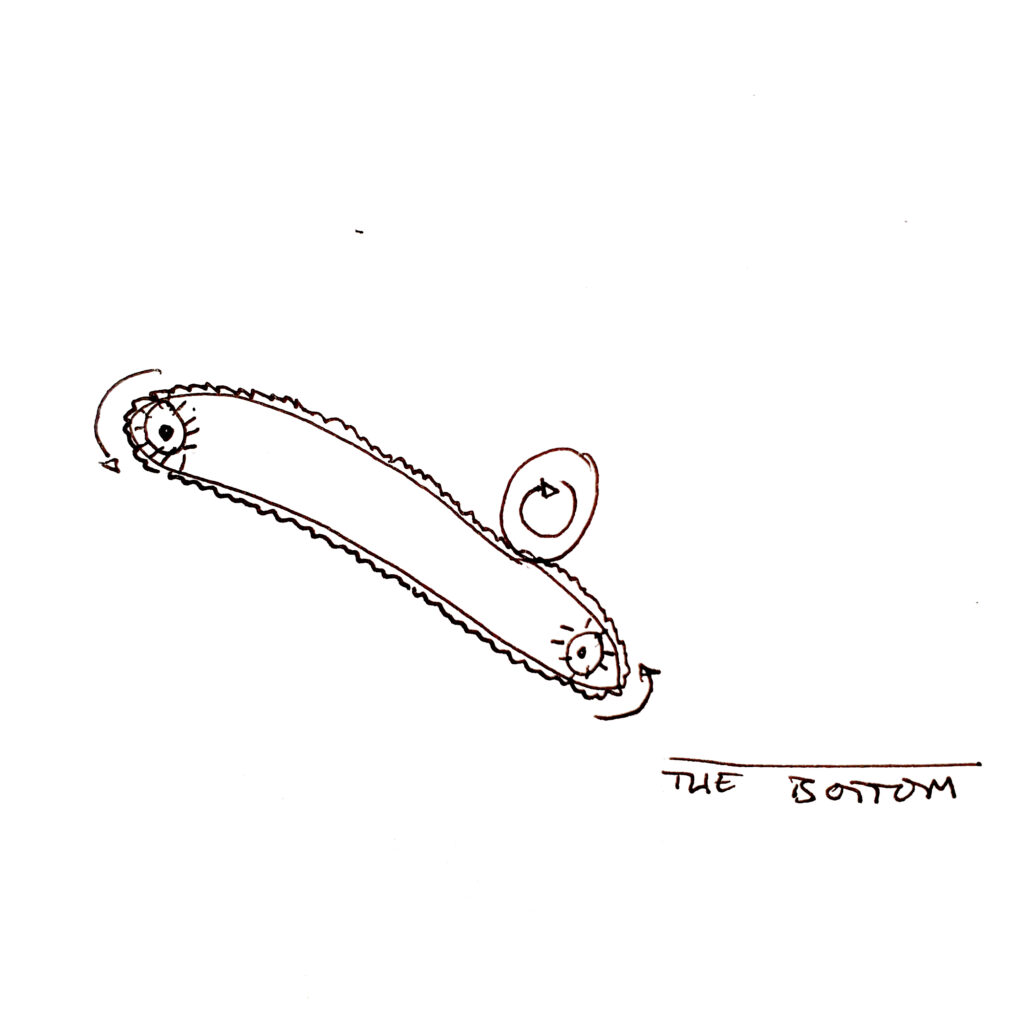

The fluctuations that are inherent and continuous in the liquid surface across all axes of movement are the consequence of a myriad of factors: wind, oceanic currents, gravitational pull(s), continental topographies, depths… and at the very basic level, the form and material of the surface beneath the liquid, we can call this the ‘sub-surface’. At the same time, however, that sub-surface is rearranged by the continuous movement of the water, taking on the shape of a ripple, by the material being lifted and deposited in particular locations as opposed to others; the surface as we know it is broken up, shifted, and reconstituted. There is a quality of continuous, repetitive, and different movement that is apparent – and so there is no ‘Site’ as can be described by its relative position to other material (see for example, the description of the opening scene of Act 1, in Samuel Becket’s, Waiting for Godot: [23]

A country road. A tree.

Evening.

That is to say, there is no stagnant site, one without moving points shifting, changing landscapes are the only given. As Samuel Becket opens his play Waiting for Godot with simple scenography, he provides us with two objects and a time. Their spatial relation to each other is completely undefined, however, they simply exist in one time, ‘evening’. It is for the stage director to place them within the frame of the stage, open for rearrangement.

This relative ‘sitelessness’ is further enforced by an unsituated understanding of place: site gives way to non-site (Smithson, & Flam. 1996). [24]

In the words of the otherwise speechless character, Lucky: [25]

‘[…] flames the tears the stones so blue so calm alas alas on on the skull the skull the skull the skull in Connemara in spite of the tennis the labors abandoned left unfinished digger still abode of stones in a word I resume alas alas abandoned unfinished the skull the skull in Connemara in spite of the tennis the skull alas the stones Cunard (mêlée, final vociferations) . . . tennis . . . the stones . . . so calm. . . Cunard . . . unfinished . . .’

Because to claim finitude is to reject duration. The finished state is an illusion as much as five centimeters or three hours are. Since there is no stagnation, only movement, the work can never be finished – like Sisyphus, [26] only, without effort to accomplish our supposed goal (of progressing), we are in a state of continuously rolling downhill, never to reach…

How exactly to know where any one thing is in a system of moving parts, other than to assume for the time-being that they are not moving, and give measure from one surface to another. It is the distance between these surfaces that make the difference – and recognize that the measure will never be true. It is a cruel trick we play on ourselves by aiming for a precision that does not exist, not in the absolute – rather, it is asymptotic, tending to perfection but never reaching it. Instead, an average, or mean will have to suffice. Since we can never truly provide the height of the water’s surface, a position at which it is never existing is instead selected: the mean level, at all times both above and below the water’s surface. The meanness of the measure derives from its averaging abilities and its seductive promise of a knowledge we do not really have. Let us not be seduced by the siren song that a definition seems to provide: the false security that one knows something with absolute certainty.