THE ARCHIVE

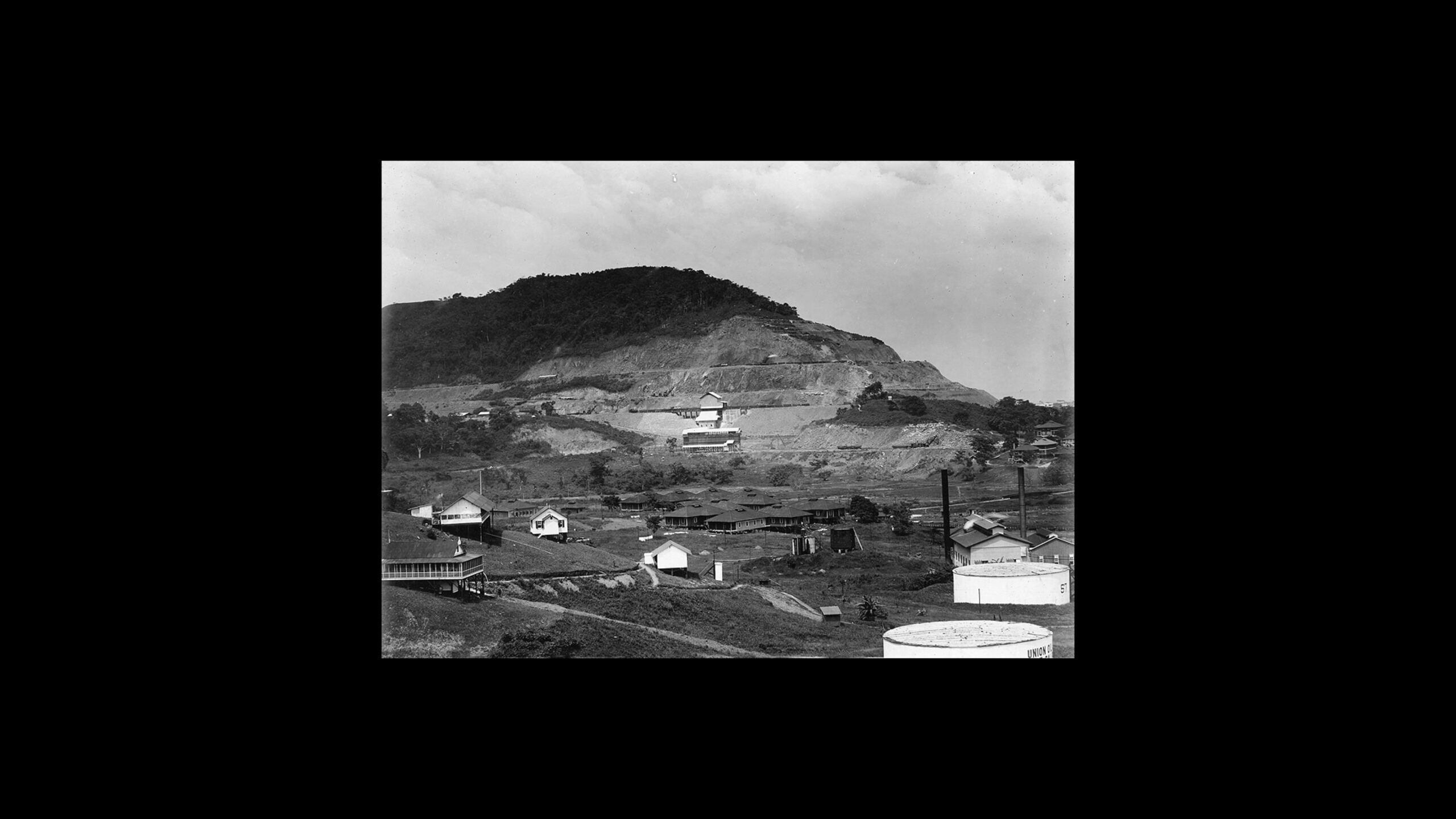

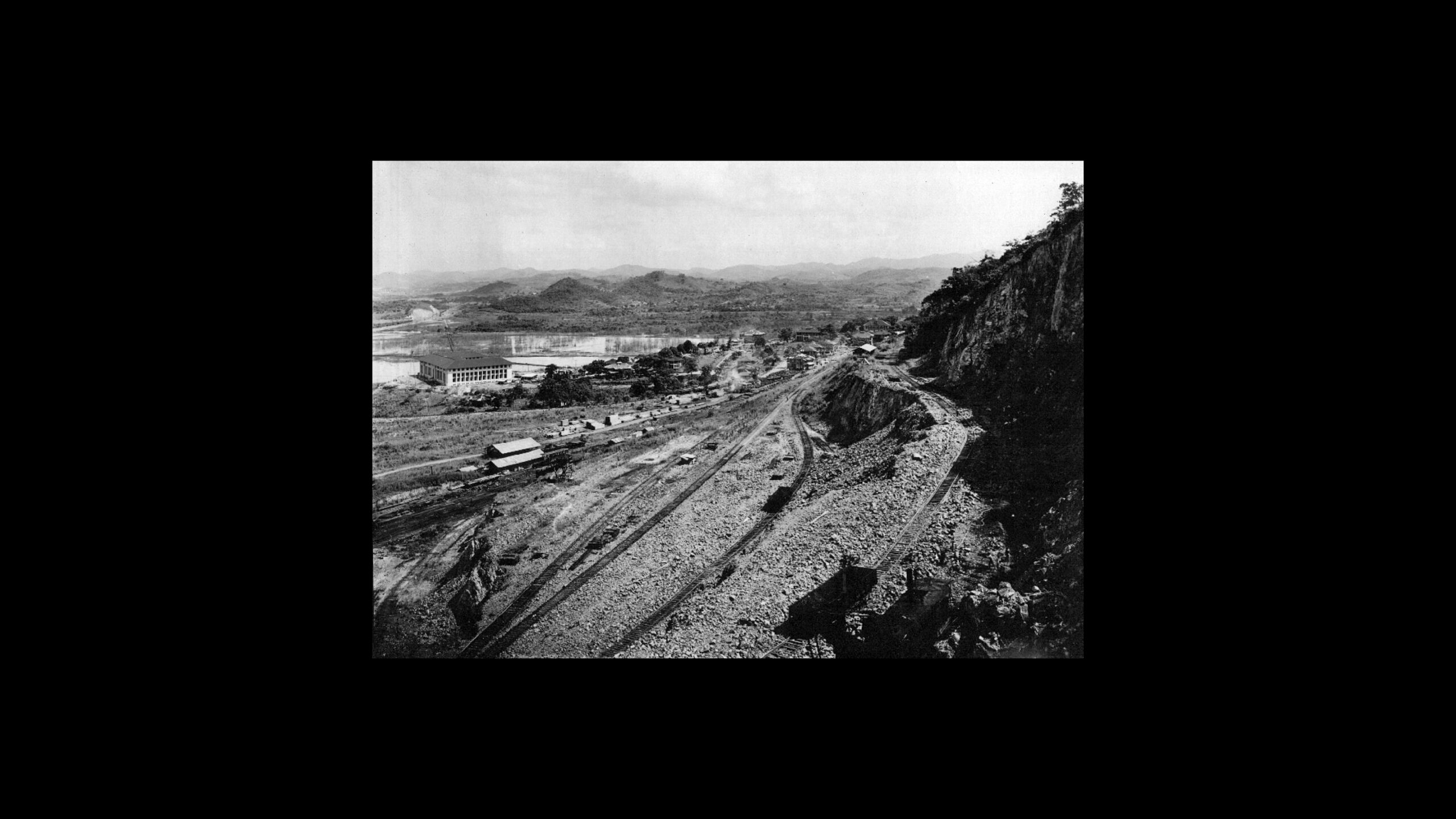

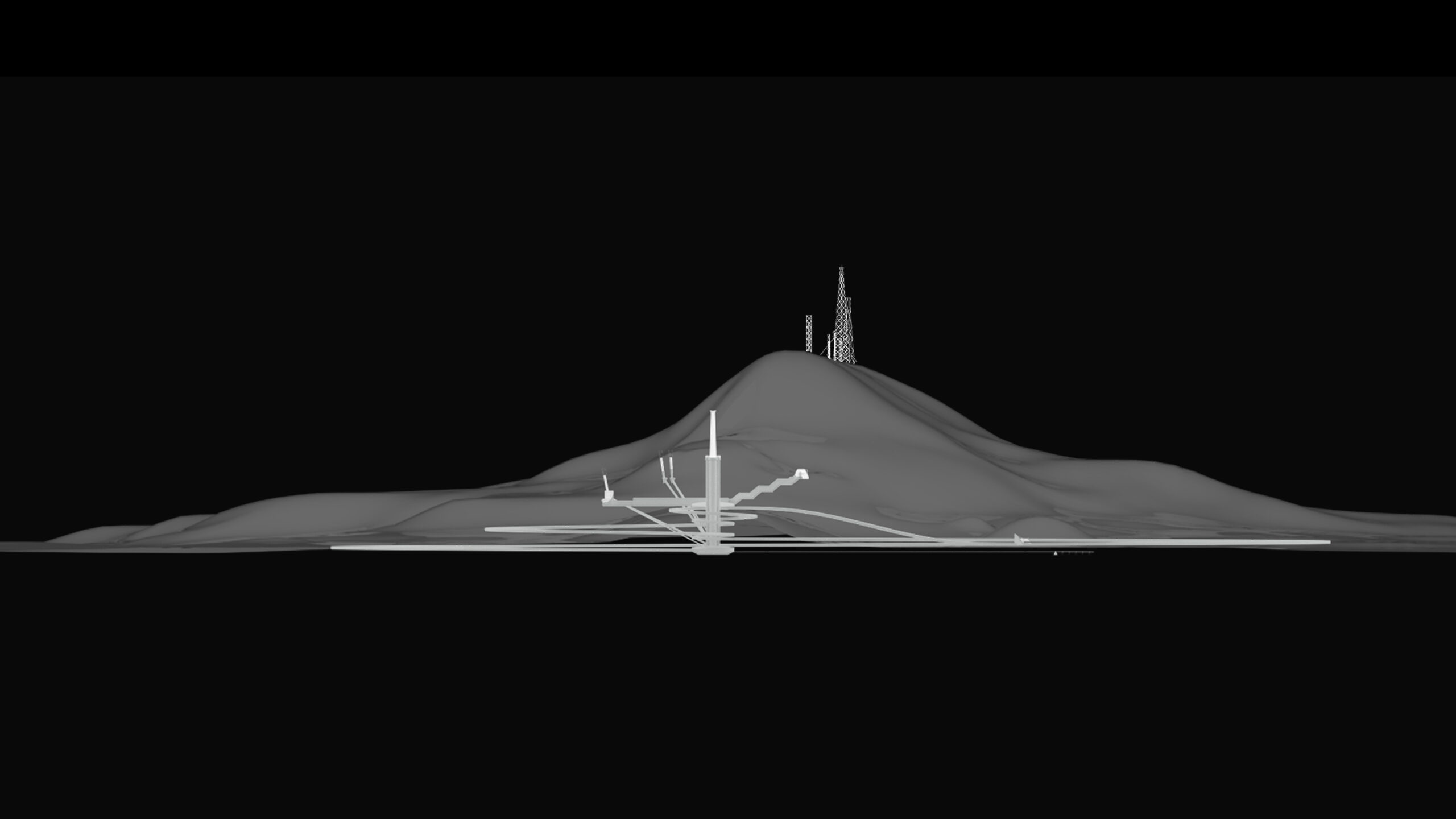

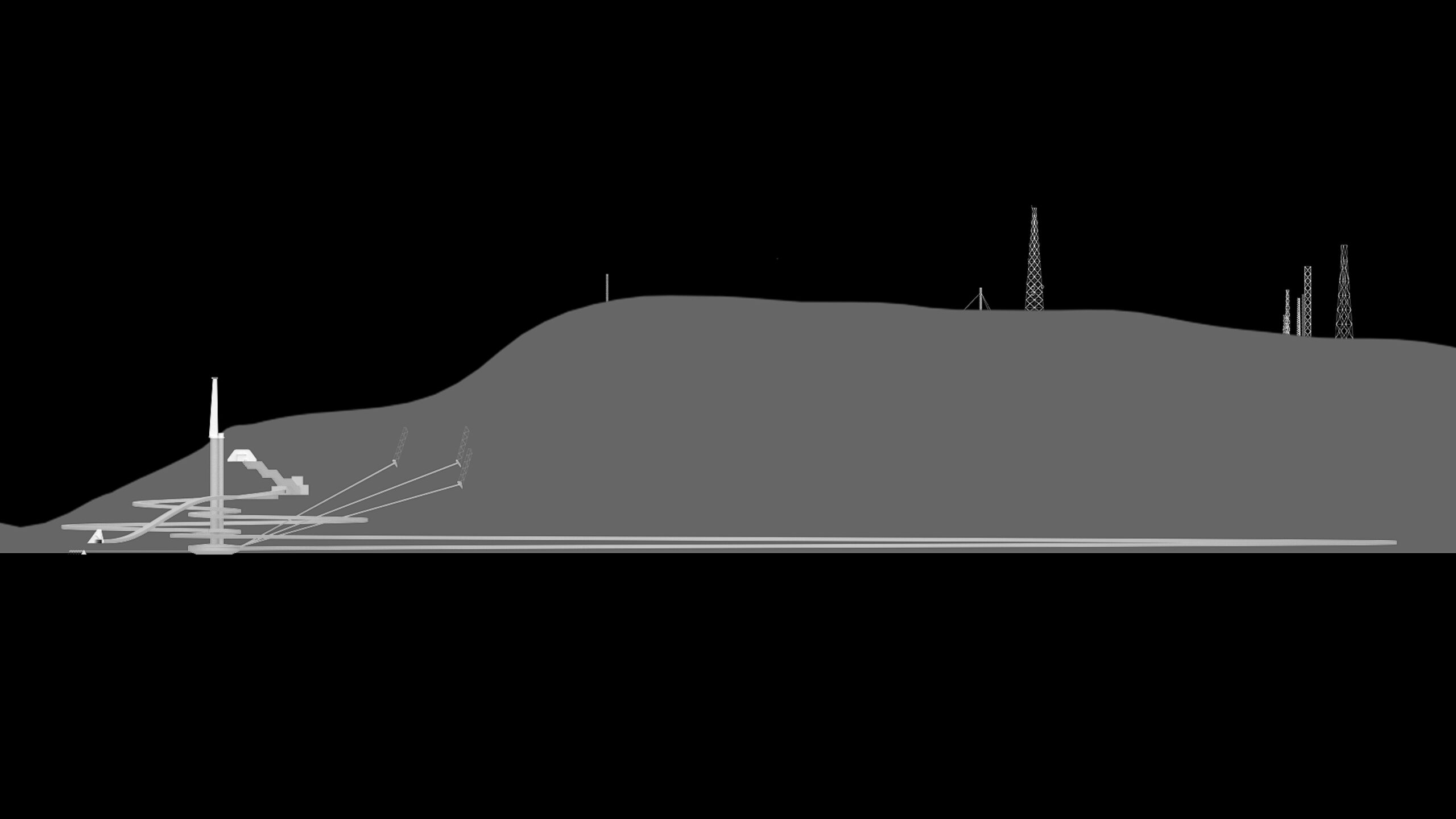

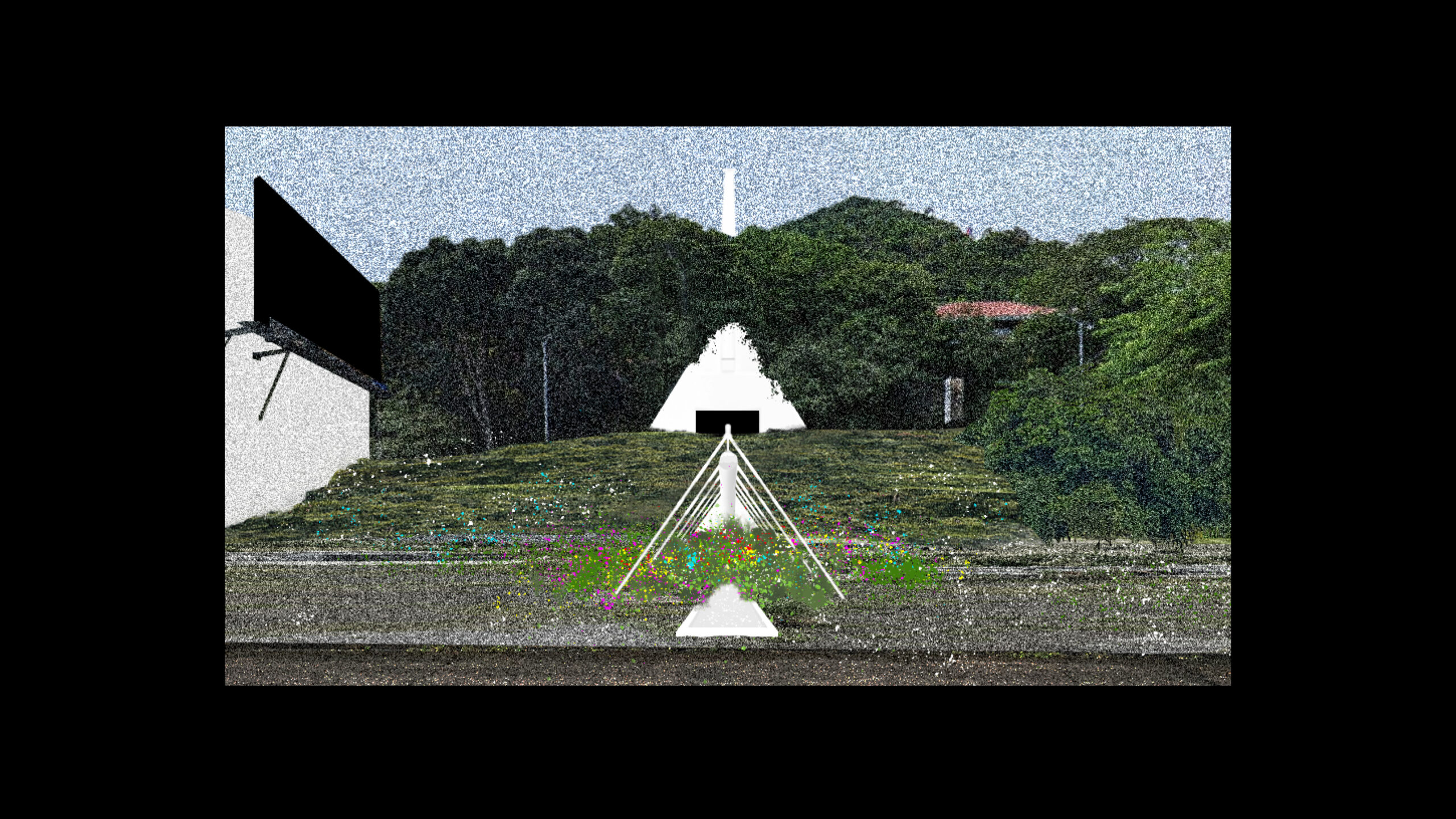

The Archive is the centrepiece of the project, positioned in the central node of the strategic constellation, located on Ancon Hill. Most famously, Ancon Hill was chosen as the location of the Southern Command Headquarters which included a military bunker dug into the hill to provide a secure location from which US military operations were directed in Panama and beyond. In addition to that, a few decades prior to the construction of the bunker, the site has been home to one of two main quarries which had provided rock used in the construction of engineering structures of the Panama Canal. Over the course of four years, more than 2.4 million cubic meters of rock have been extracted from the slopes, giving shape to the distinctly terraced terrain on the western side of the hill. Covered in deceivingly lush vegetation which has overgrown the formerly violent incursions, the slopes still house the former colonial US Canal Zone Administration building (today Panama Canal Authority administration) and the town of Quarry Heights (which the US SOUTHCOM called its home).

However, other stories of the hill are no less important. A key supply of fresh water, it not only influenced Panama City’s eventual location,[28] but also became a key element in the formation of a distinctly Panamanian national identity, as best captured in the writings of Amelia Denis de Icaza. Icaza, one of the most foundational writers and poets in the cultural landscape of what was to become Panama, turns to Ancon Hill as a place to which to tie ideas and feelings of a new Panamanian self-consciousness. Speaking of the hill with great sensibility and admiration, Al Cerro Ancon (1908) is primarily concerned with the colonial appropriation and ecological destruction of the hill by the newly established US administration.

‚‘You no longer keep the traces of my footsteps,

you are no longer mine, idolized Ancon.

That destiny has already untied the ties

that my heart formed in your skirt.

Like a lonely and sad sentinel

a tree on your summit I met:

there I engraved my name, what did you do?

Why are you not the same for me?

What have you done with your splendid beauty?

Of your wild beauty that I admired?

From the mantle that I gazed with sturdy gentleness

I gazed upon your skirts of freedom?

What has your stream become? Has its current

Did a stranger’s footsteps dry it up?

Its crystalline, beneficent fountain

in the abyss of non-being sank.

What has your stream become?

Did a stranger’s footsteps dry it up?

Its crystalline, beneficent fountain

in the abyss of non-being sank.‘

(online translation)

The stream mentioned in the poem, while not named explicitly, is with rather great certainty referring to an underground hydrological system that collected and channelled water coming down from the hill into the Chorrillo del Rey, a well formerly located in today‘s district of El Chorrillo – to which it gave its name. It is unclear, whether the ‘drying up’ of the stream is to be understood literally as an ecological disturbance resulting from mining operations and deforestation of the hill, or metaphorical whereby the well became obsolete and abandoned after completion of the sanitation works programme. This programme was included in the Canal Treaty and carried out by the US Army Corps of Engineers – thus a potential side-effect of the American intervention.

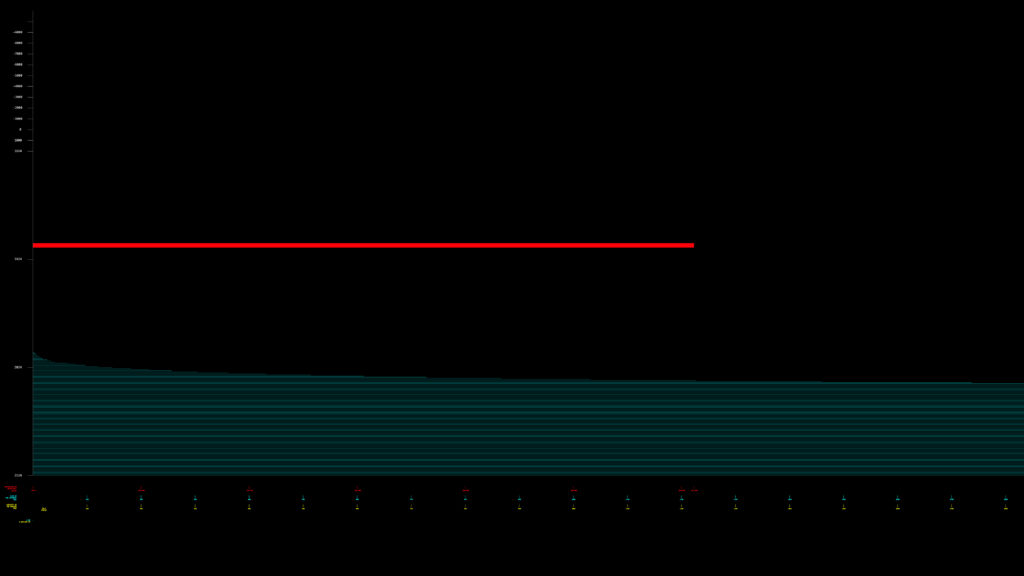

Considering historically extractive practices conducted on the site as well as the proposed programmatic necessity to store something – i.e. the Internet that grows exponentially (cyan in Figure 22) – it quickly becomes evident that if one was to follow a purely technocratic approach, it would lead to an inevitable extractive catastrophe and serious destruction of the site and the biological, cultural and social systems dependent on it.

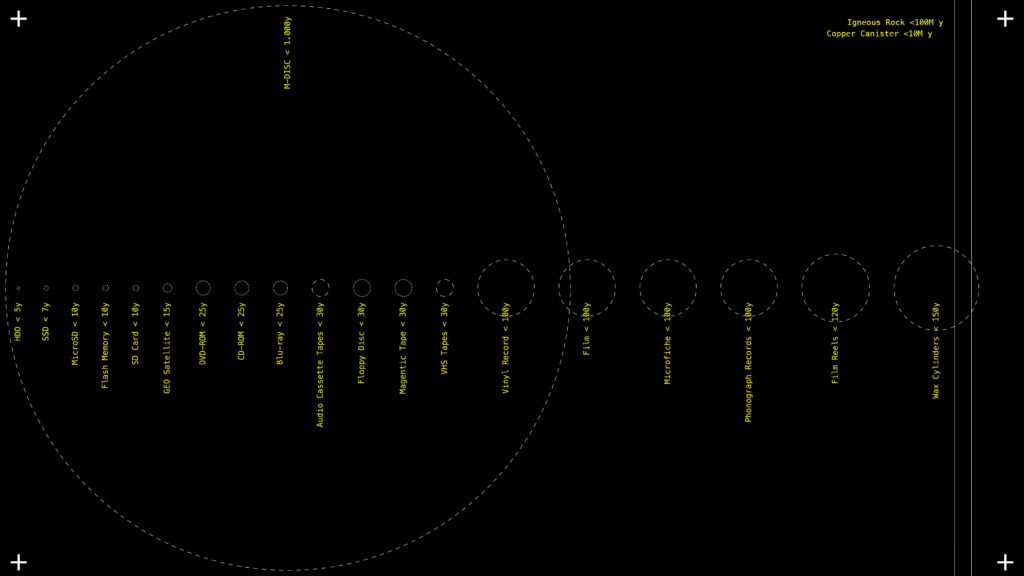

At the same time, one needs to consider what one could call Oblivion Horizon – the inevitability of the material decay of any type of hardware, whereby the only certainty one has is the loss of information and its fall into oblivion at some point in time.

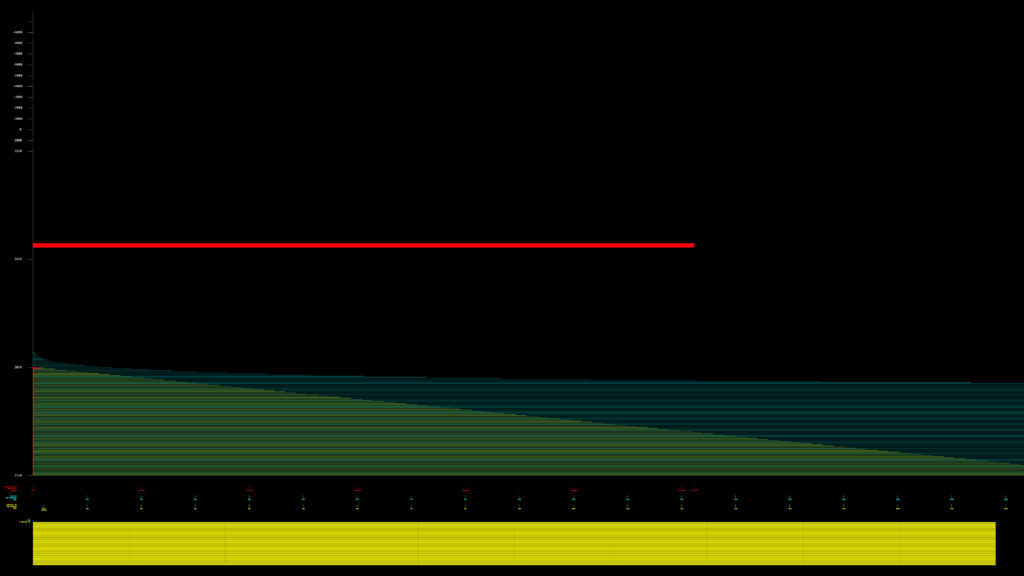

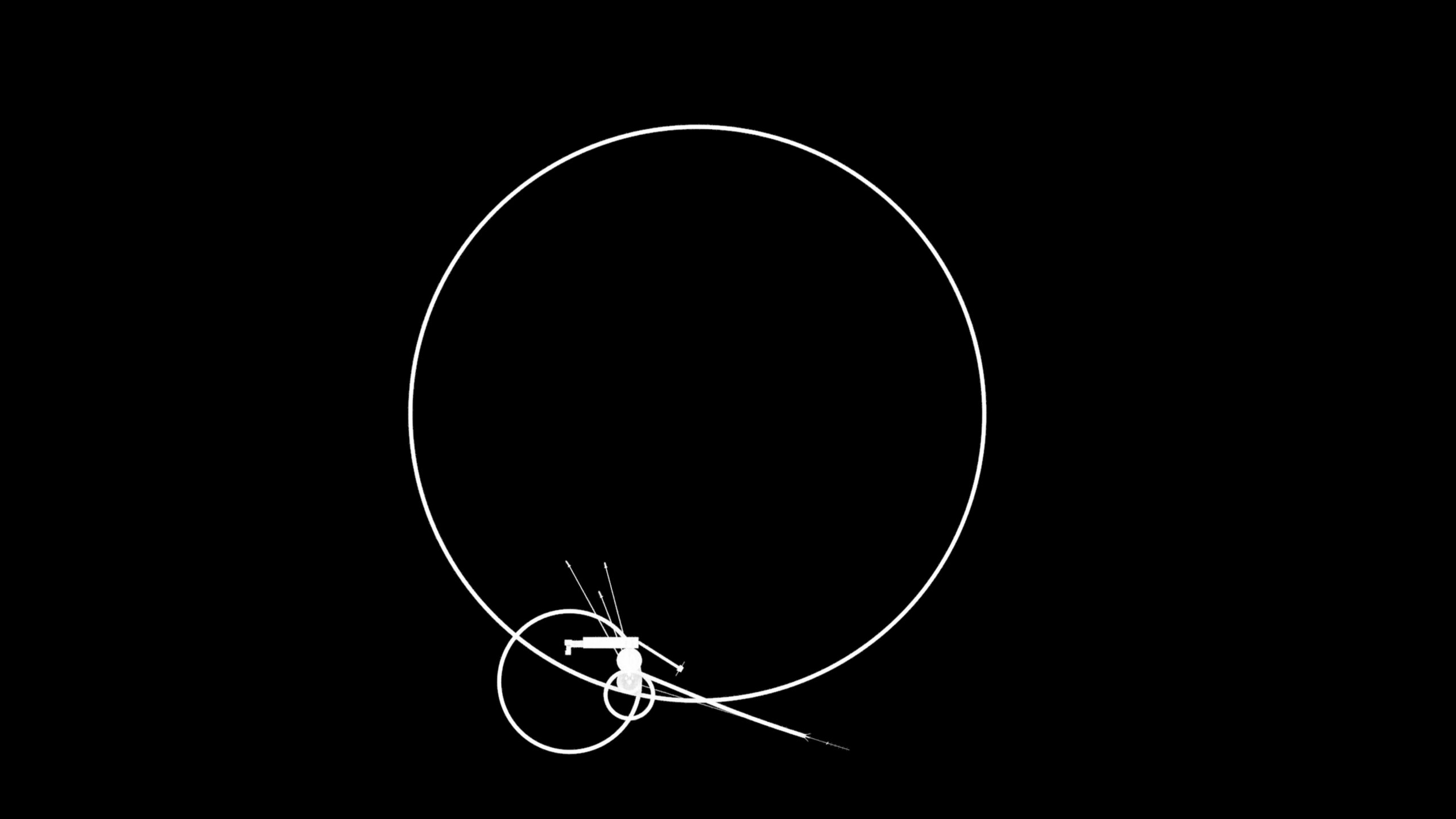

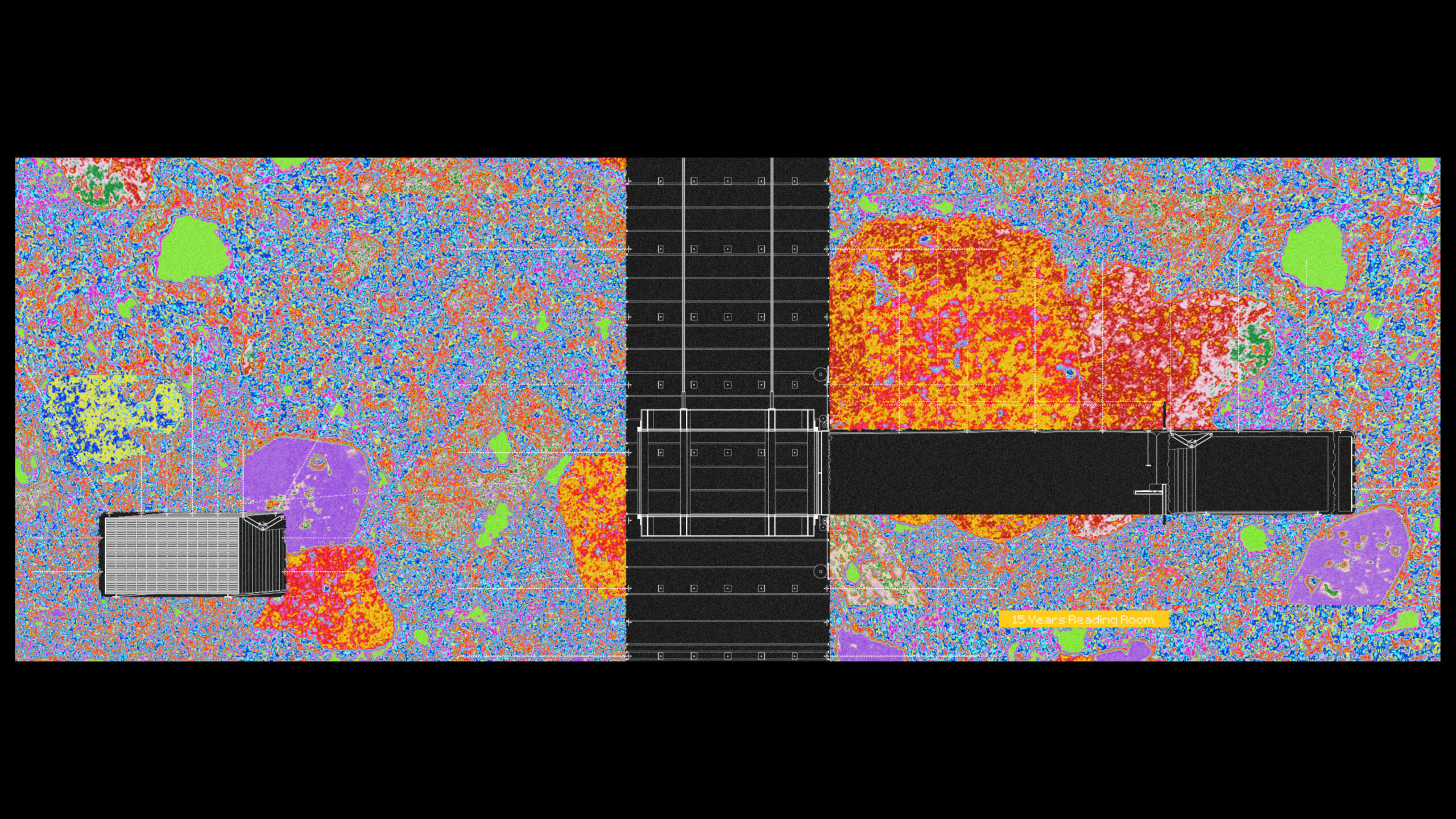

In light of this, the proposition is to not follow an ambition to store ‘everything’ on the site and instead introduce a conceptual and operational ‘ceiling’ at which data – read: material – can be added and subtracted from the hill. Here, a yearly permitted excavation rate is introduced corresponding to the average human intervention rate (red in Figure 22) into the local geological condition, counted by dividing the sum of all extracted material divided by the years of human habitation of the site, resulting in 203 cubic metres per year. This way, the storage rate is decoupled from the growth of data (cyan in Figure 22) and grows linearly (yellow in Figure 252). Now, data has to be stored consciously and selectively, with due consideration of the impact on geological and biological systems. Alongside the preservation of a fraction of information passing through the institution, it produces amounts of oblivion larger than preservation by orders of magnitude, that only keeps growing year on year.

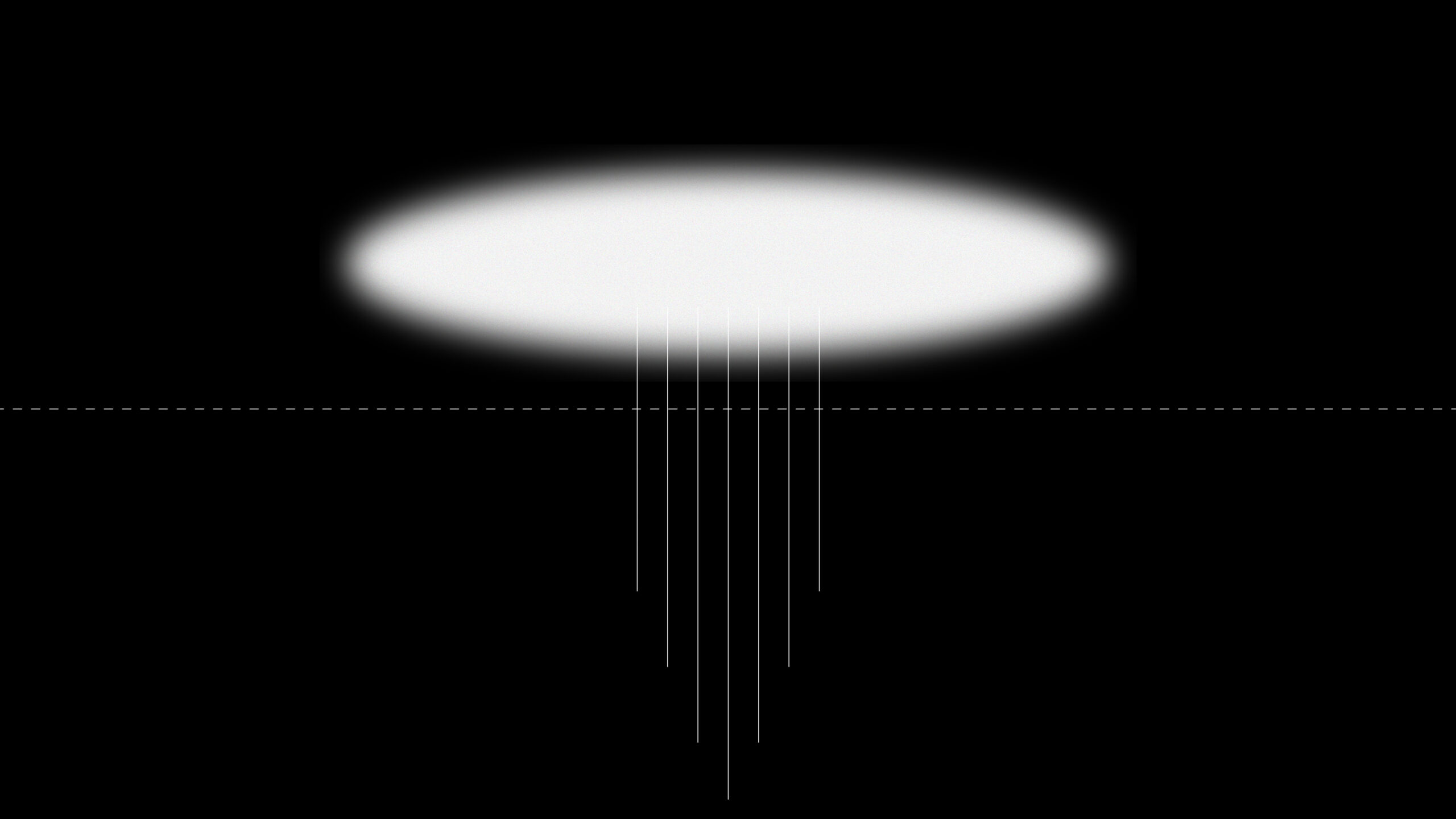

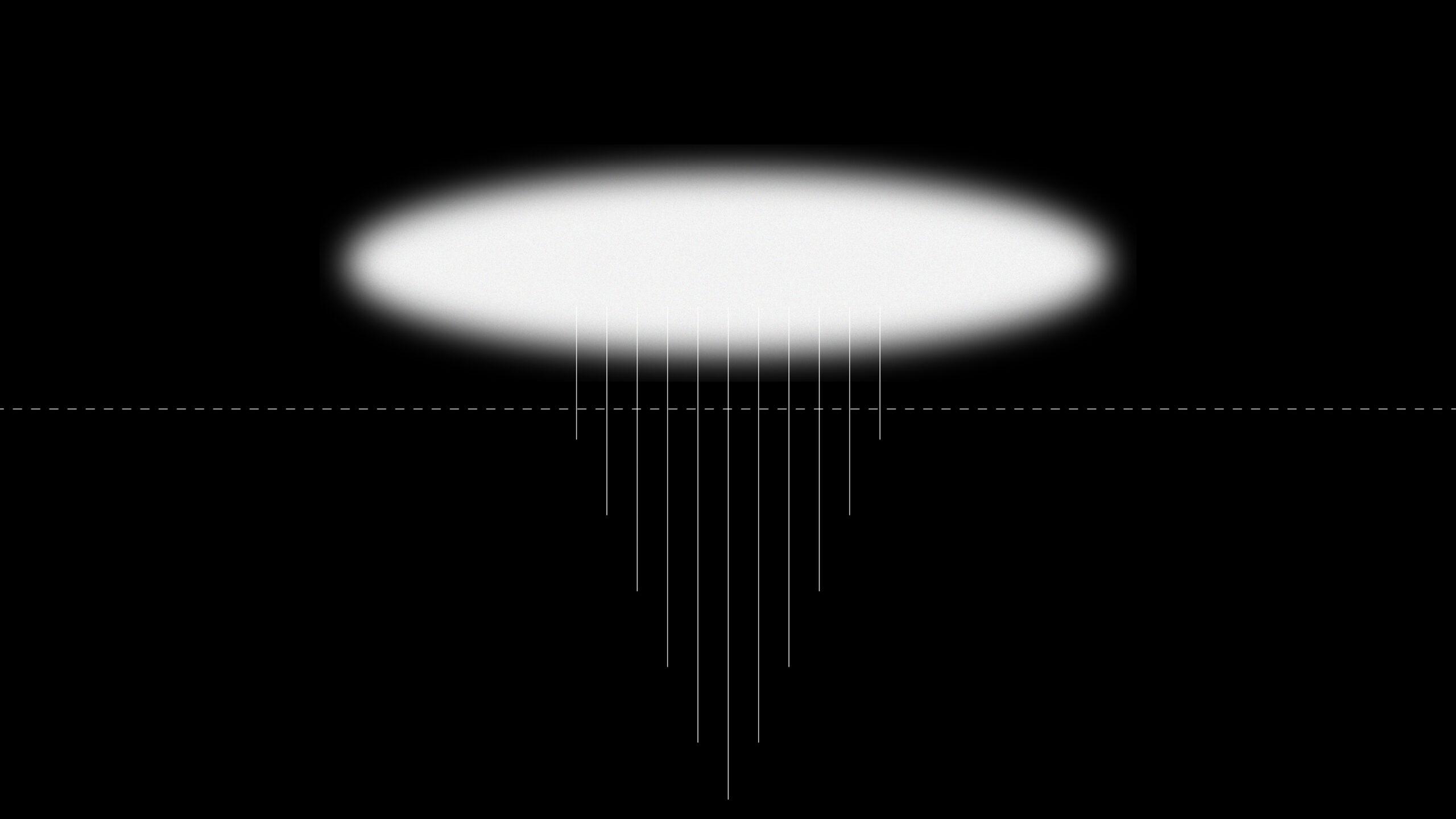

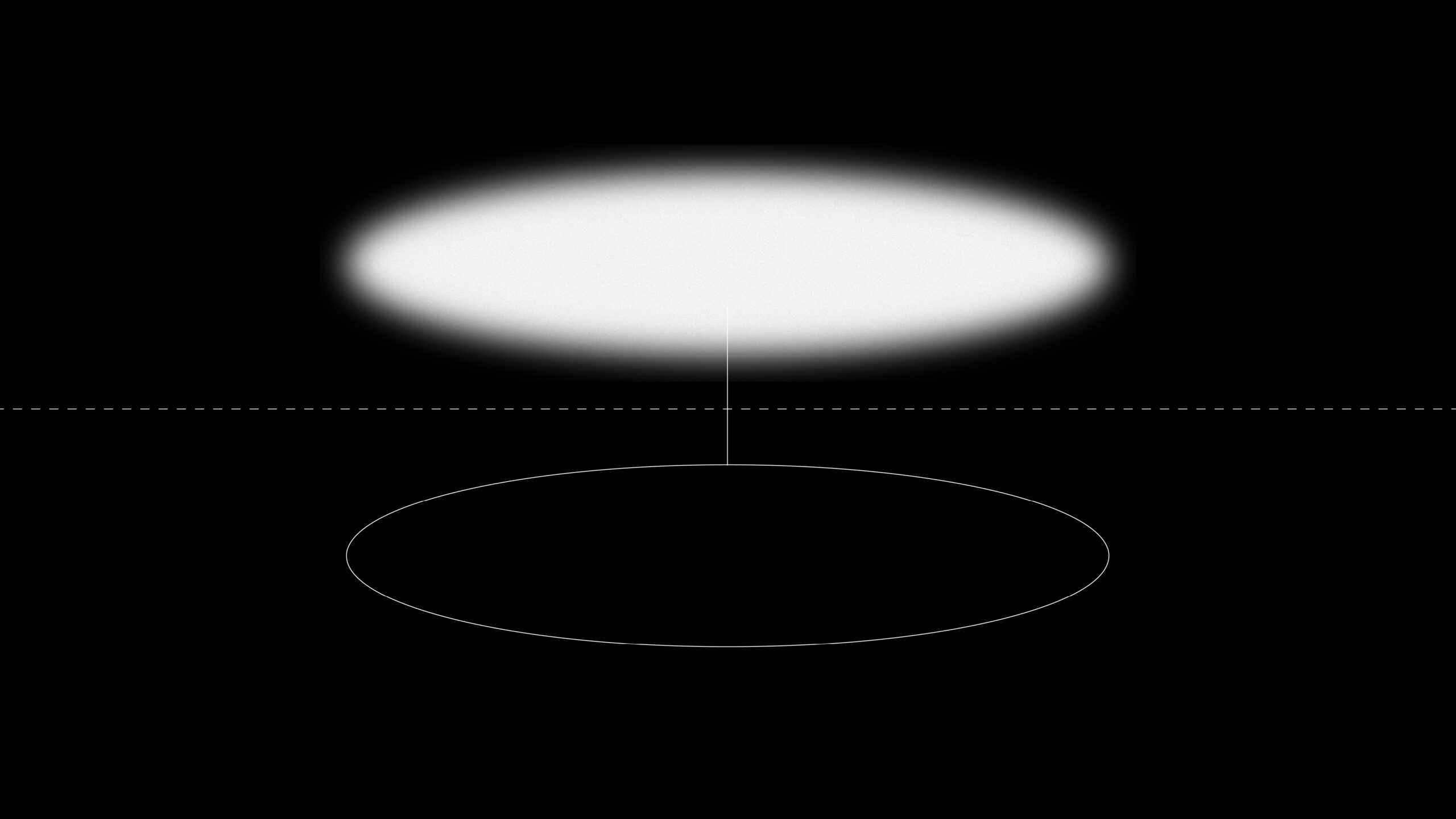

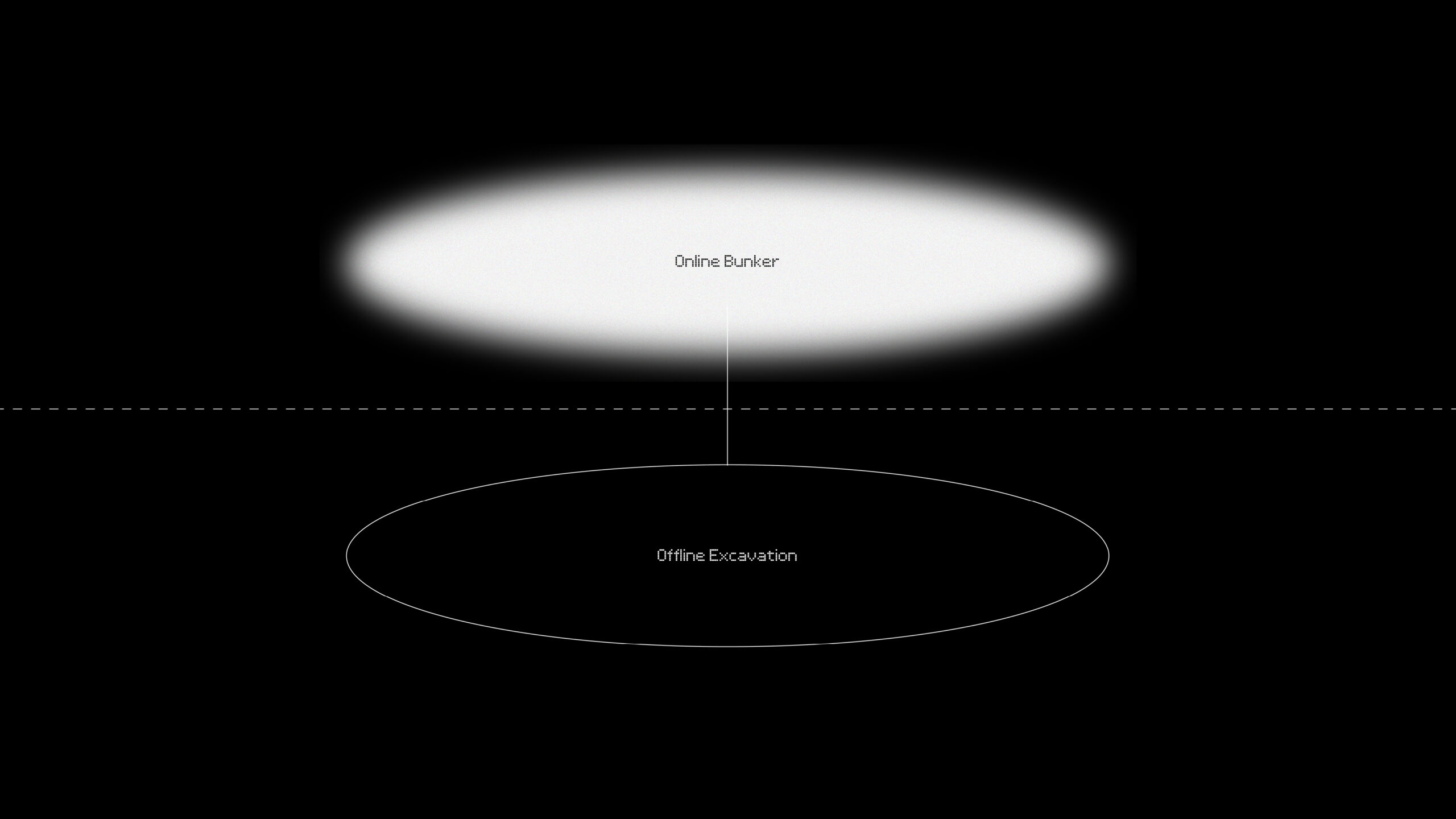

Operationally, the Archive is to have a first layer of storage, comprising an online backup. From there, data is then selectively placed into a second, offline layer into the ground. However, if one is to follow a technocratic logic of ever-expanding linear deposition, this operation would produce an ever-expanding digital dump, as the media on which data is stored inside the hill inevitably decays. Furthermore, after a certain amount of time, this storage principle would nevertheless significantly disturb the local condition through its ever-expanding mining operations.

Thus alongside limiting the yearly expansion, the proposition is to also introduce a horizon of finitude for the overall process. This way, instead of becoming a one-way dump, the Archive would allow for a constant, continuous re-engagement, re-negotiation and re-evaluation of material stored and material waiting for archival. This would necessitate a continuous need to relate the value of the content stored to the effort of storing it.

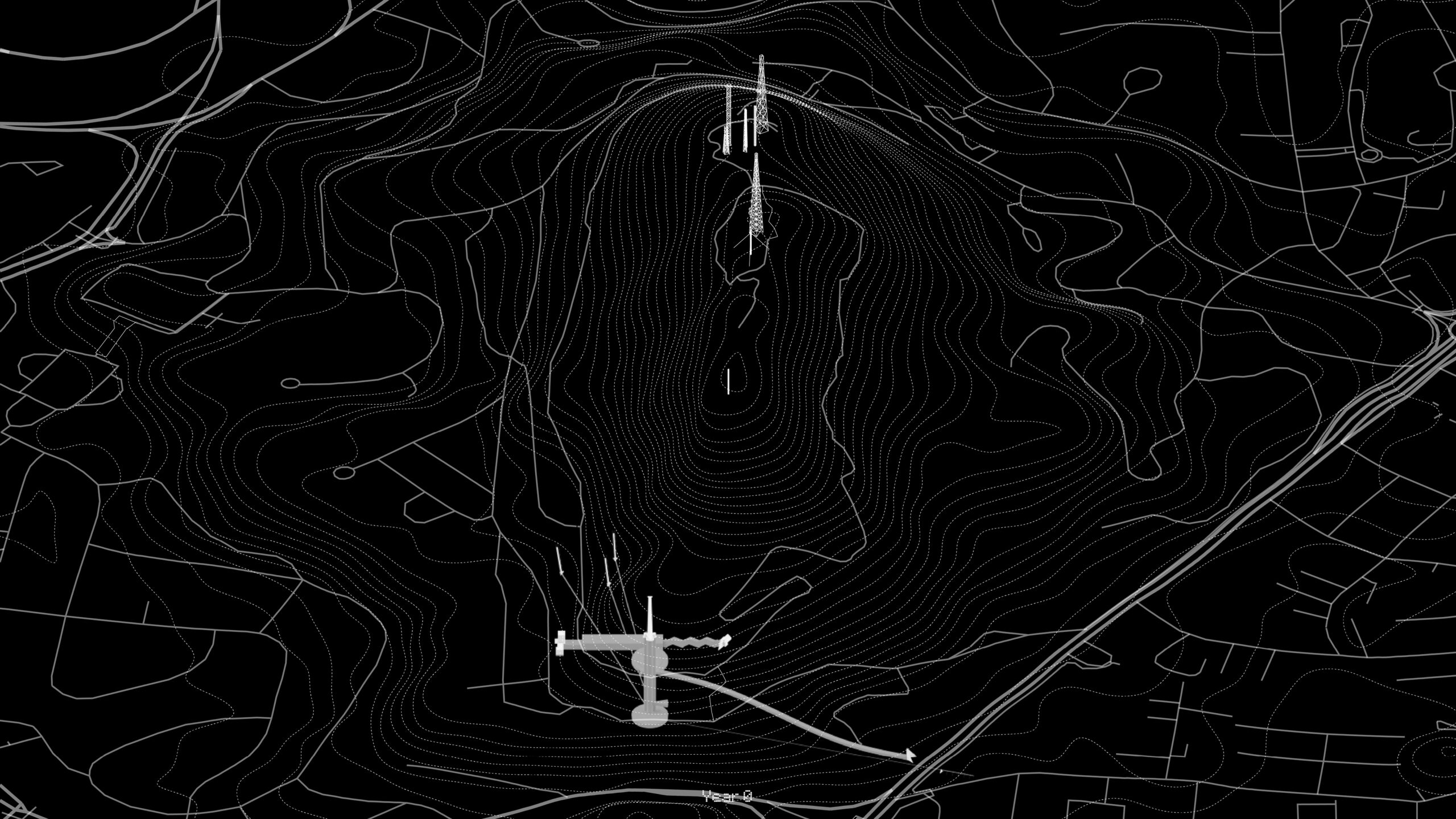

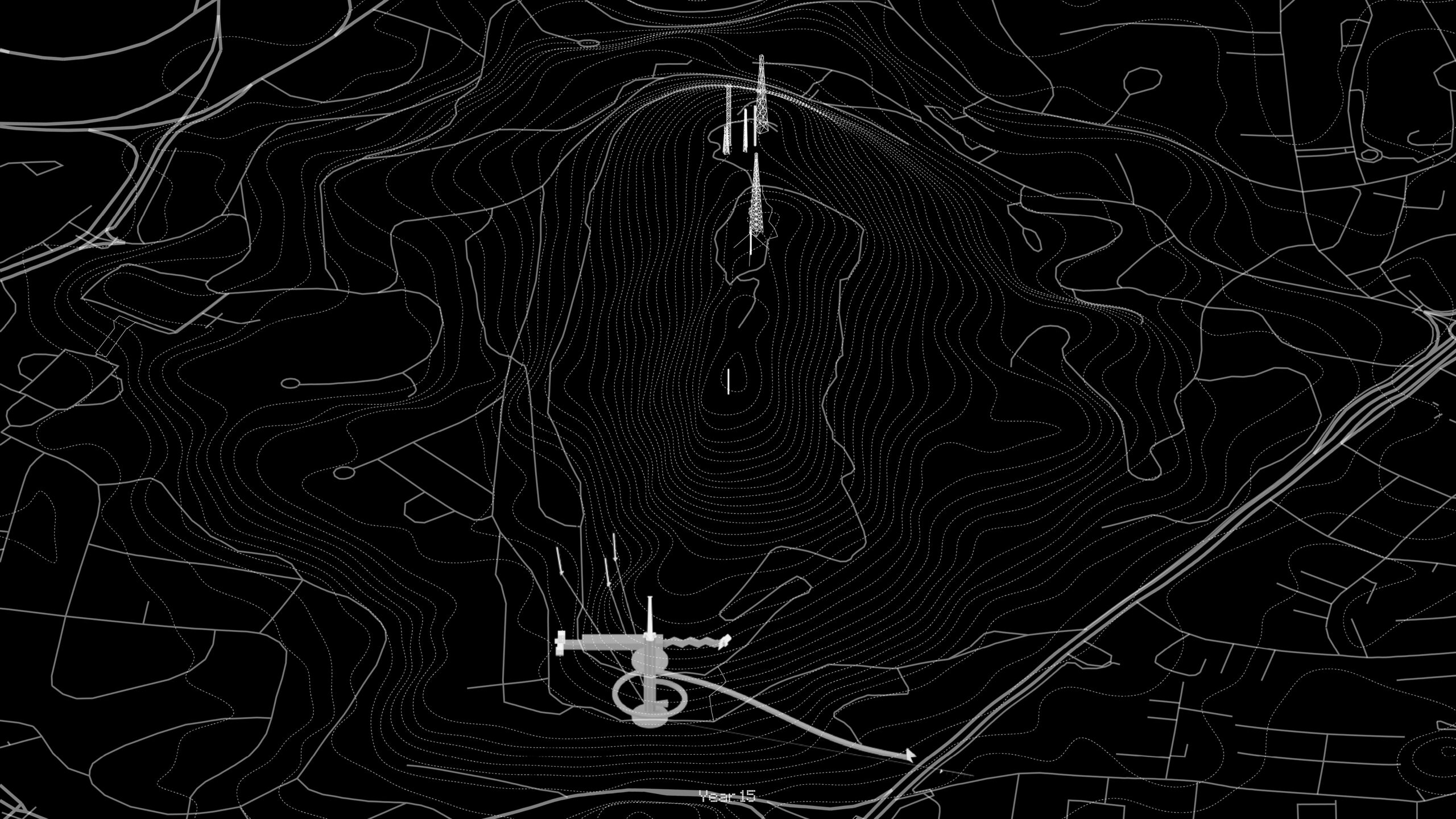

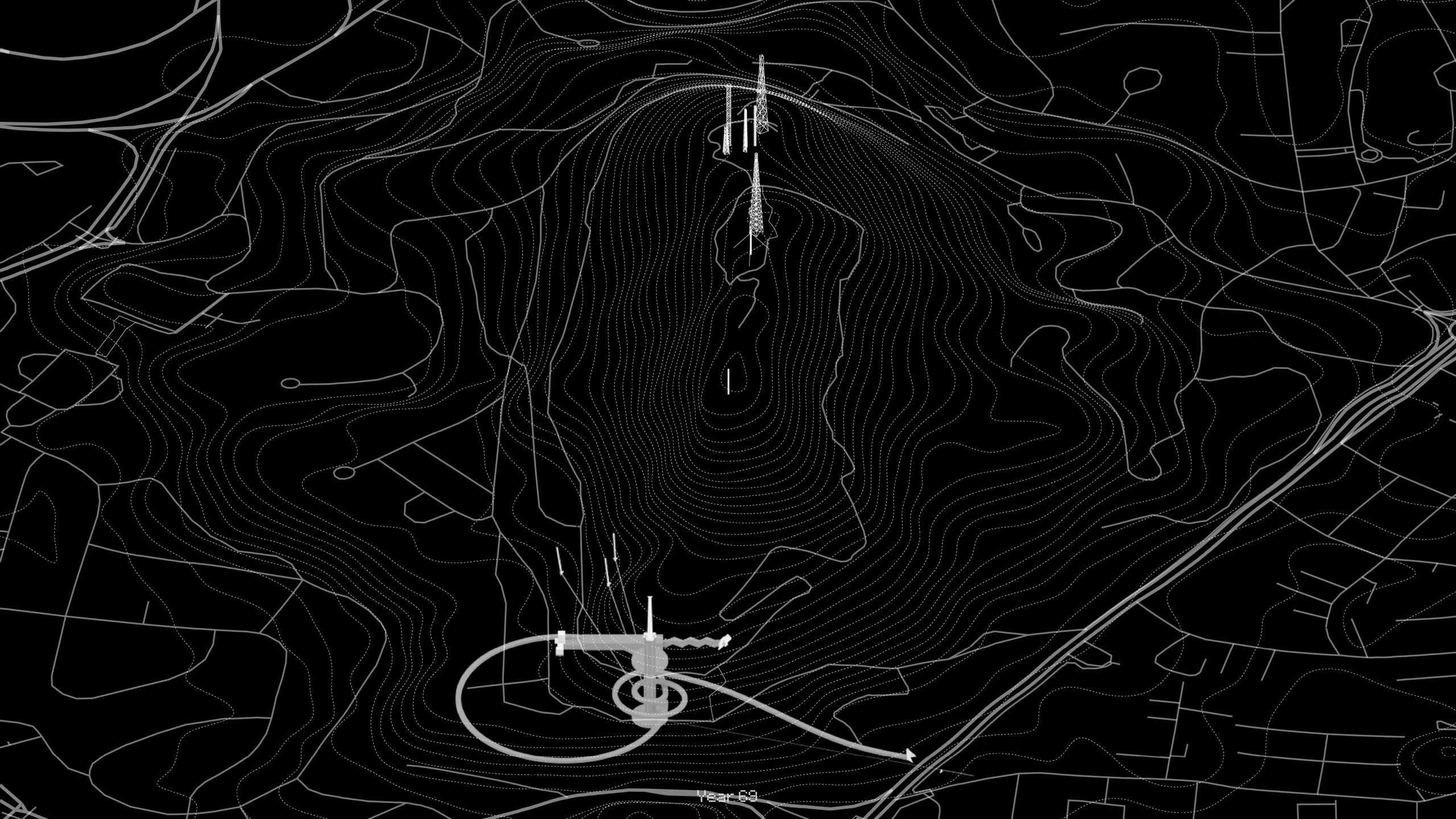

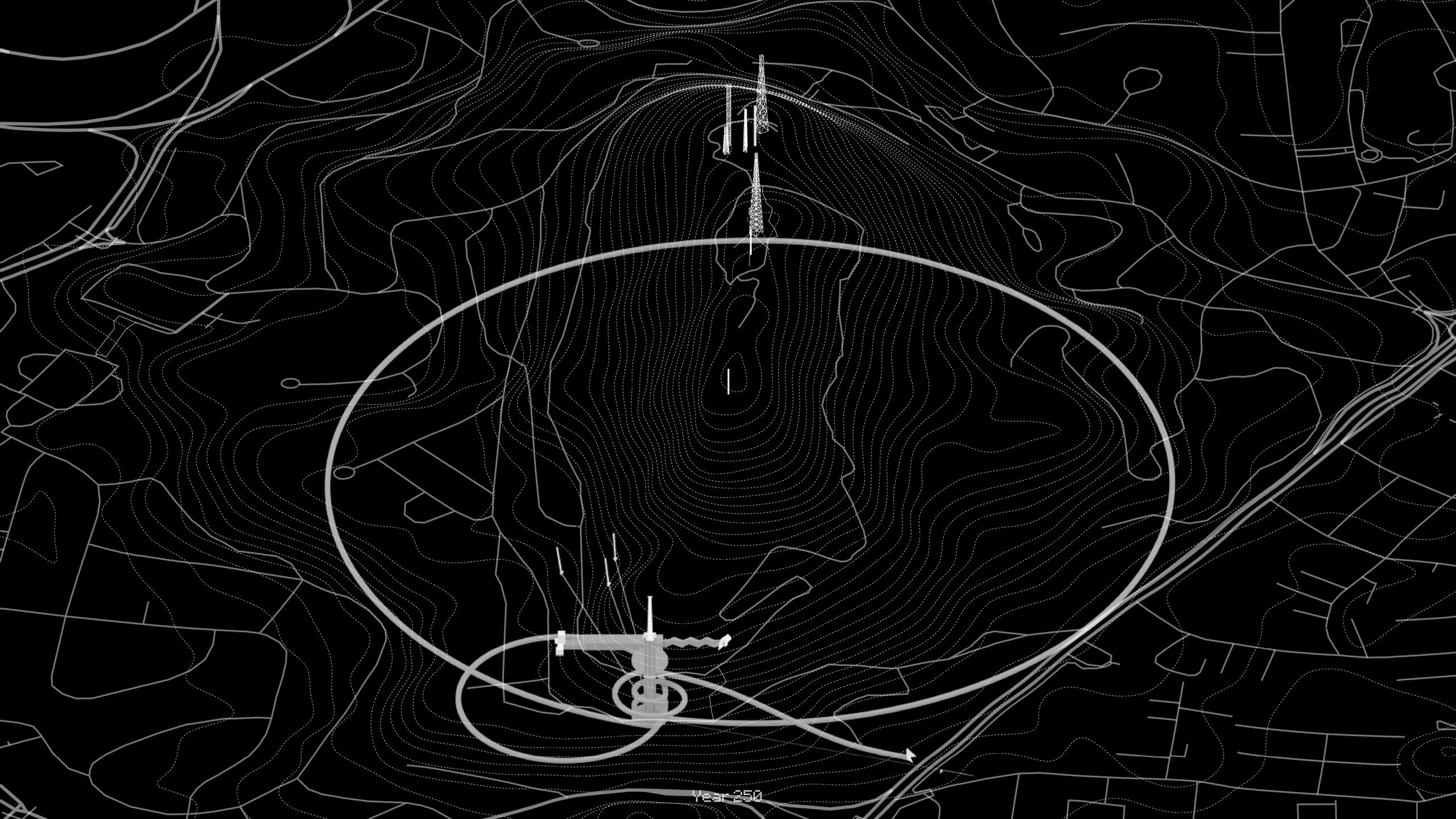

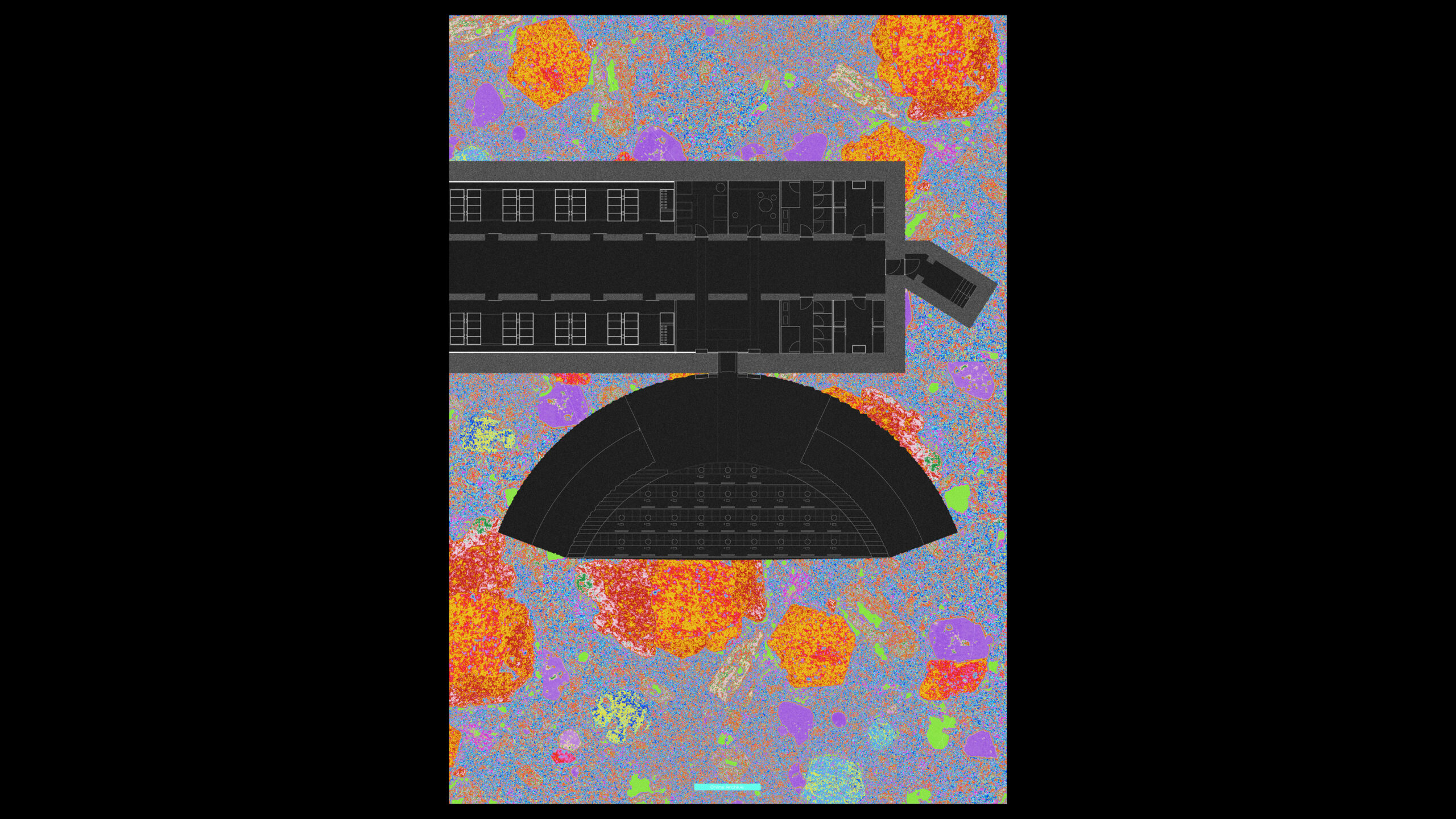

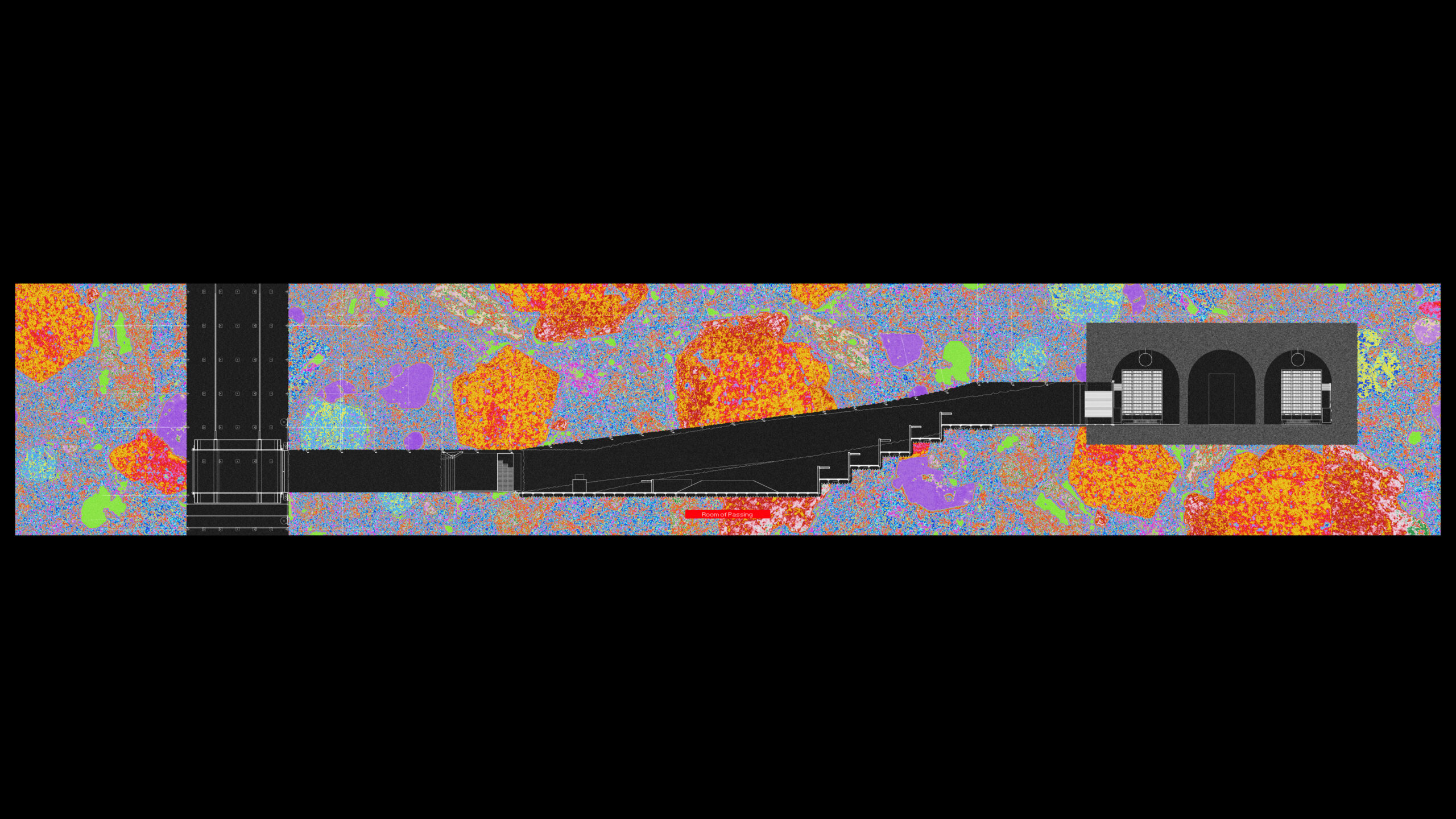

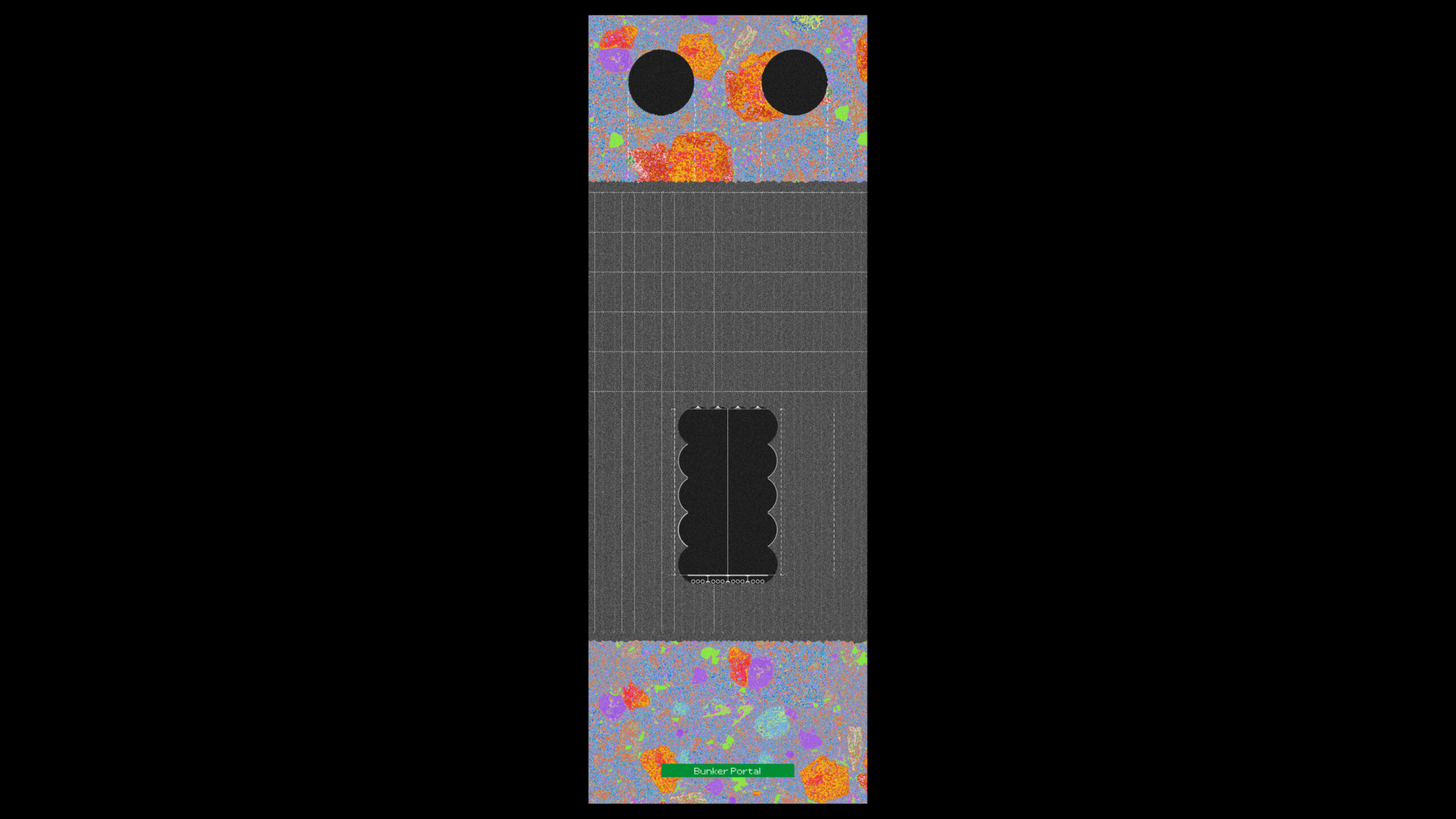

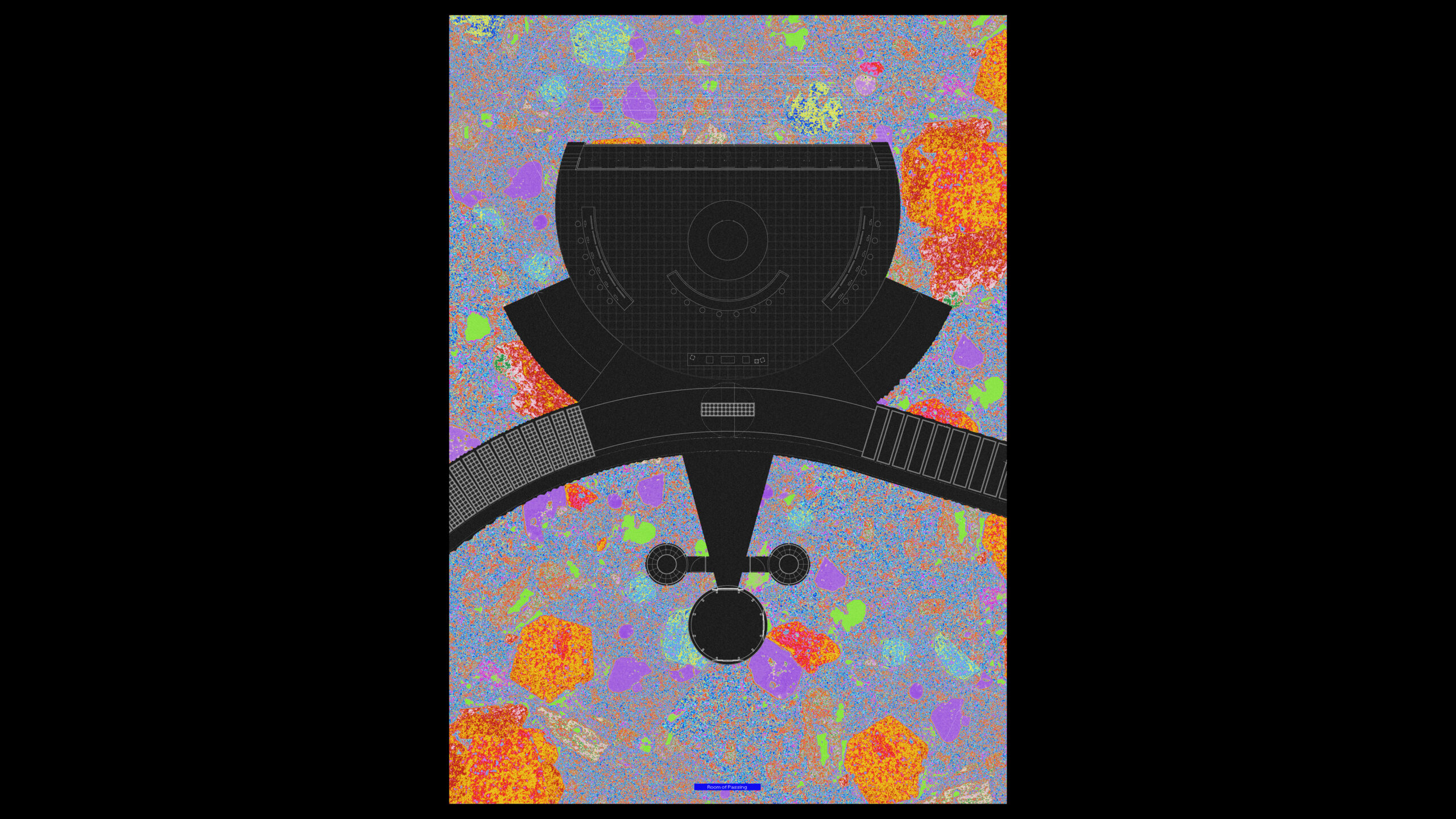

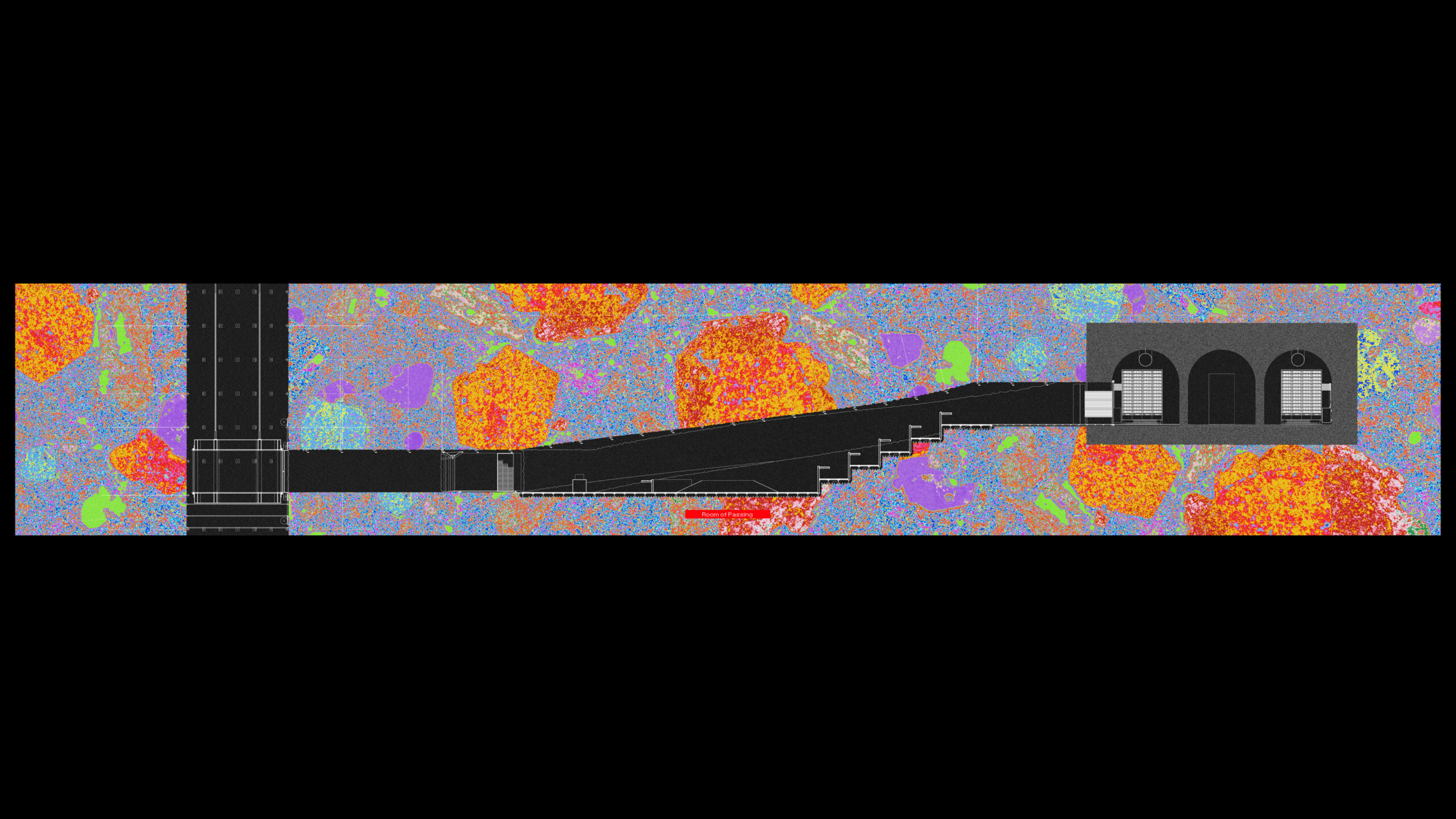

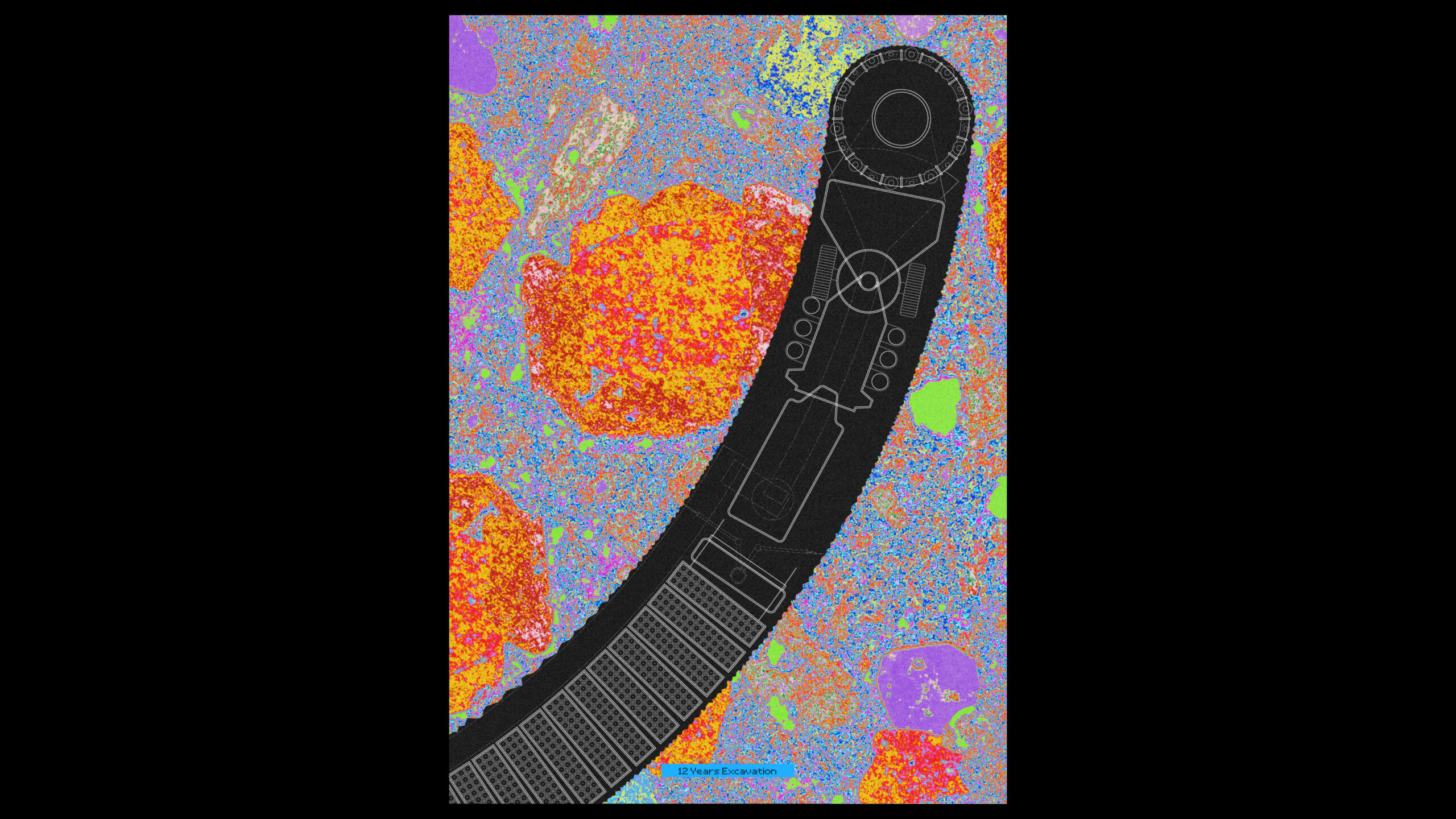

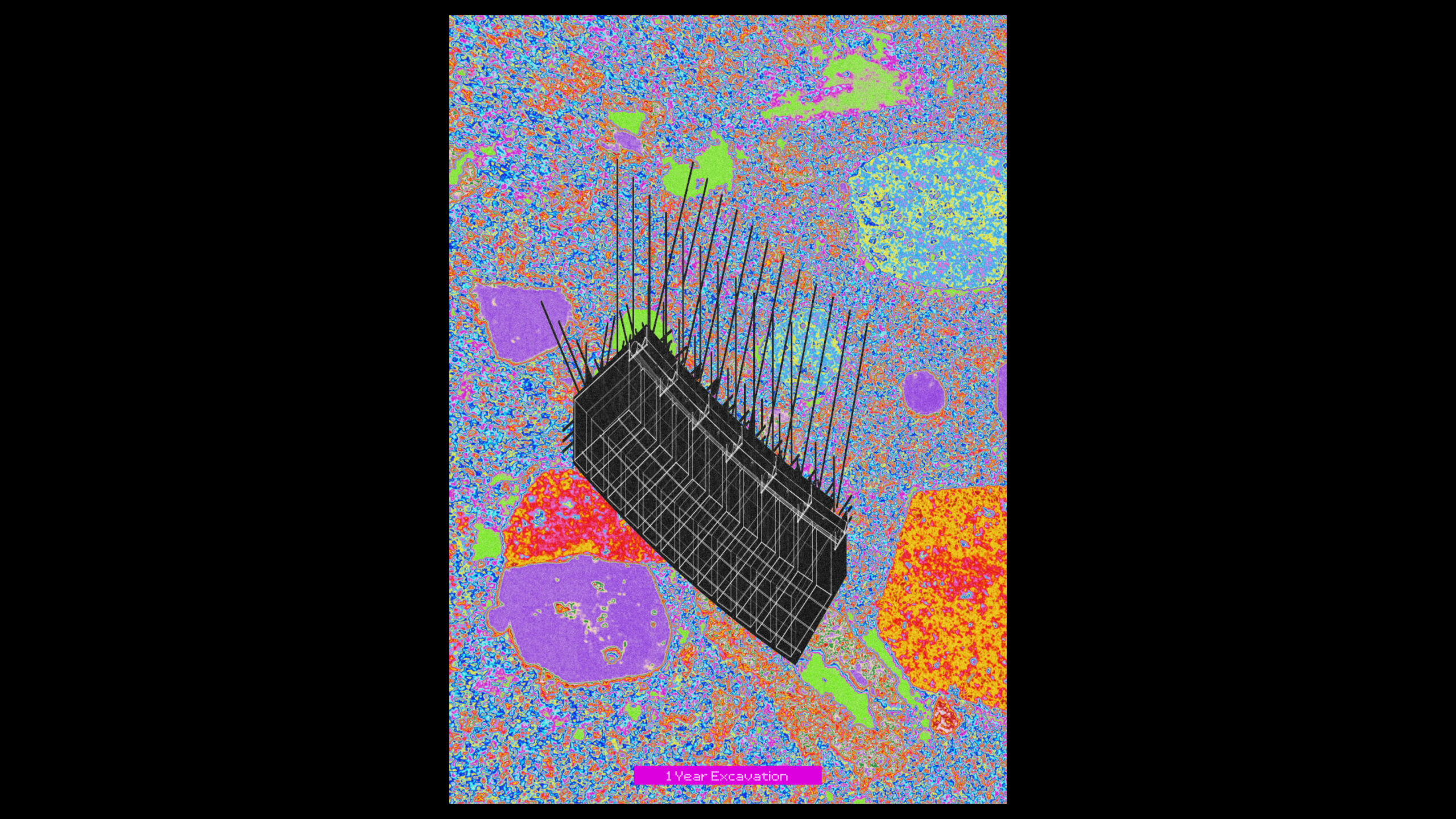

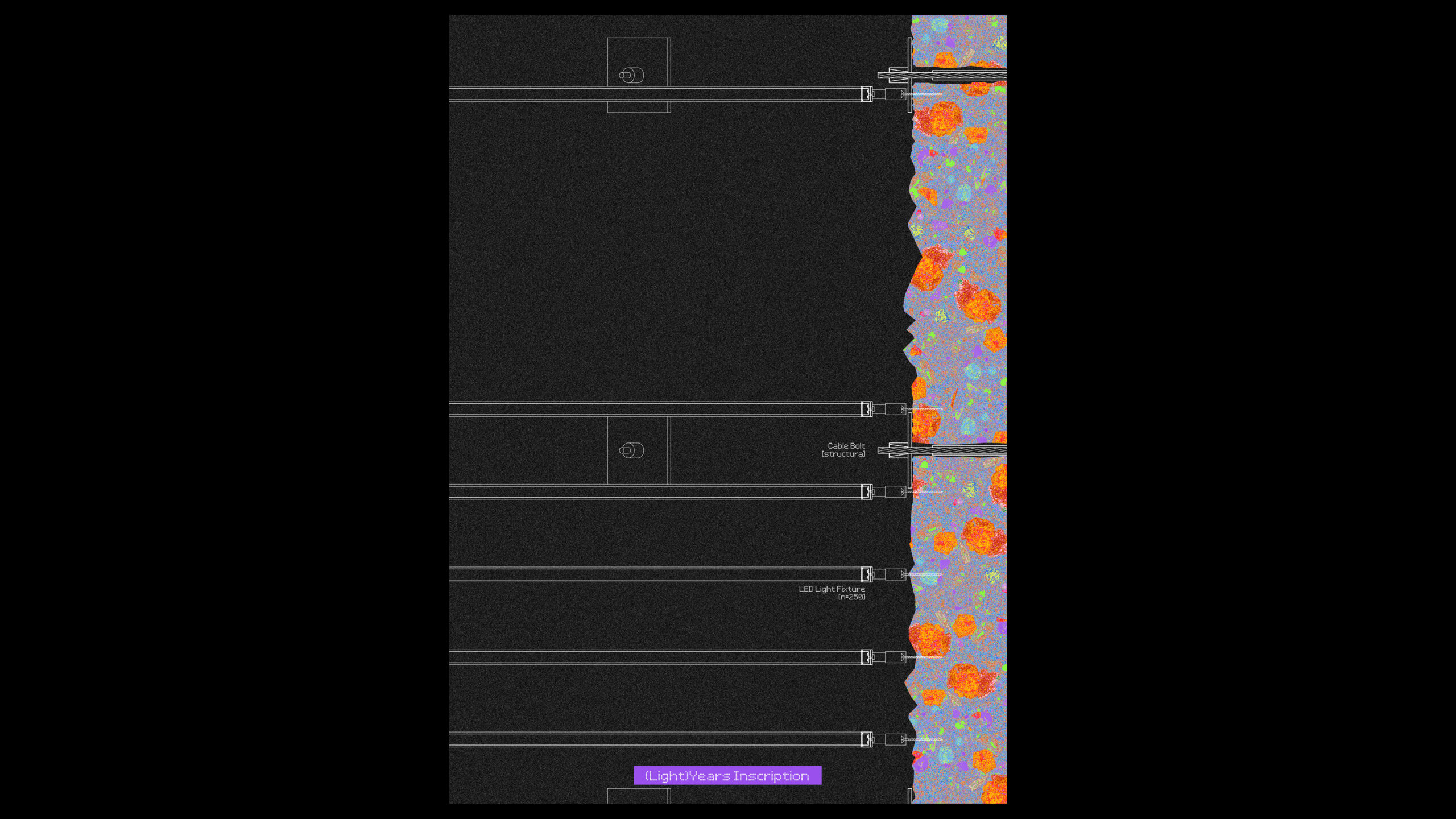

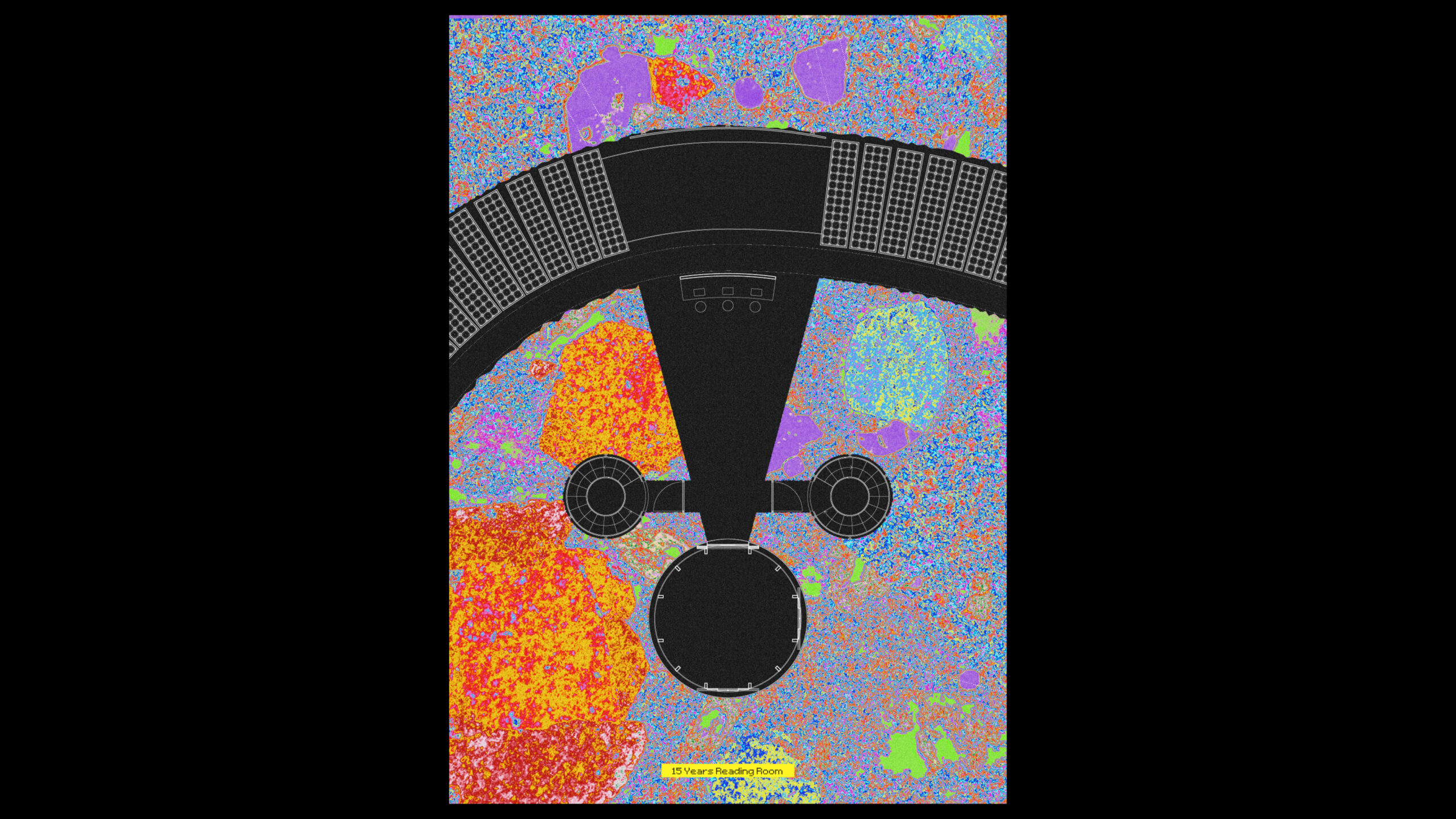

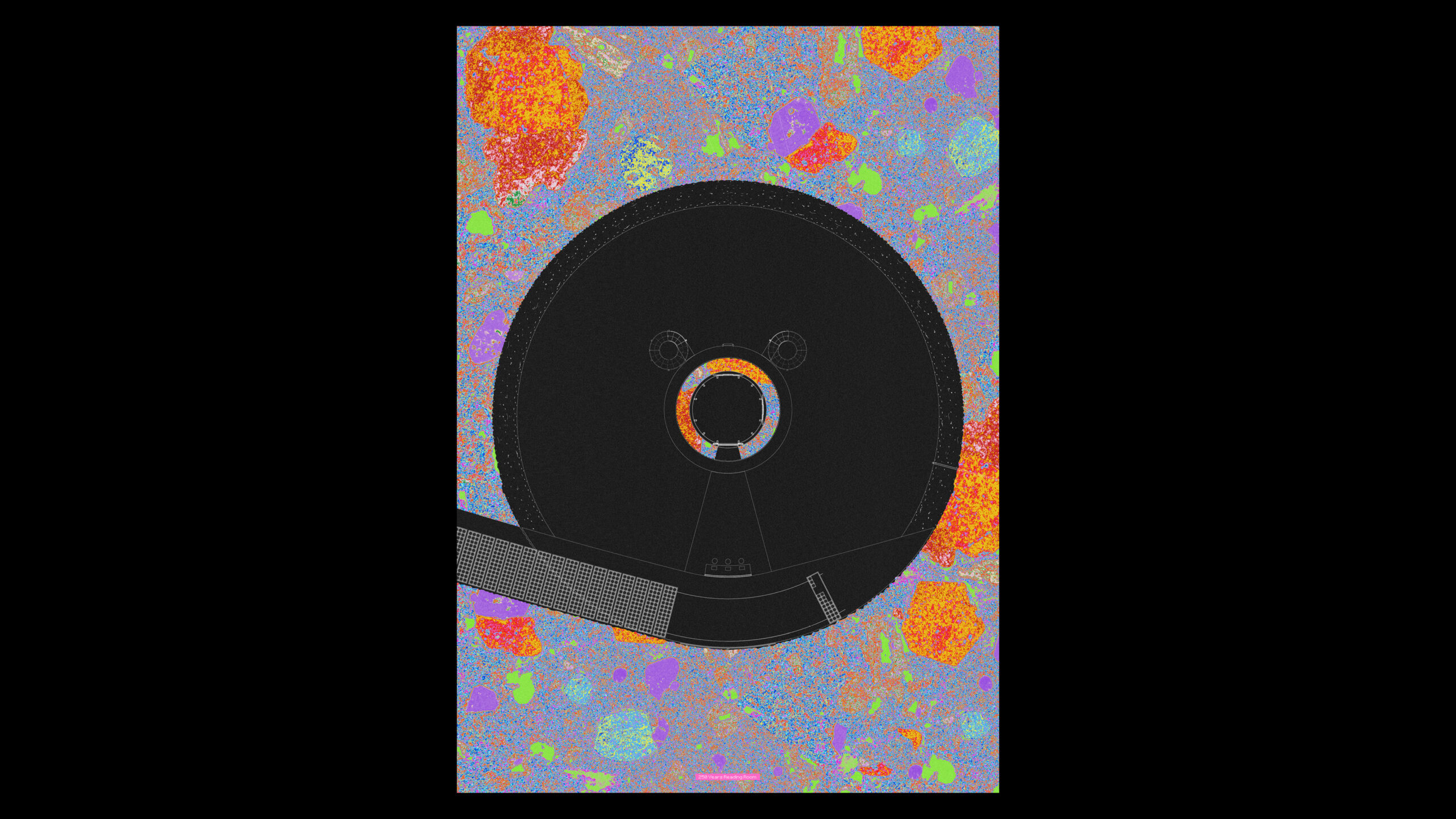

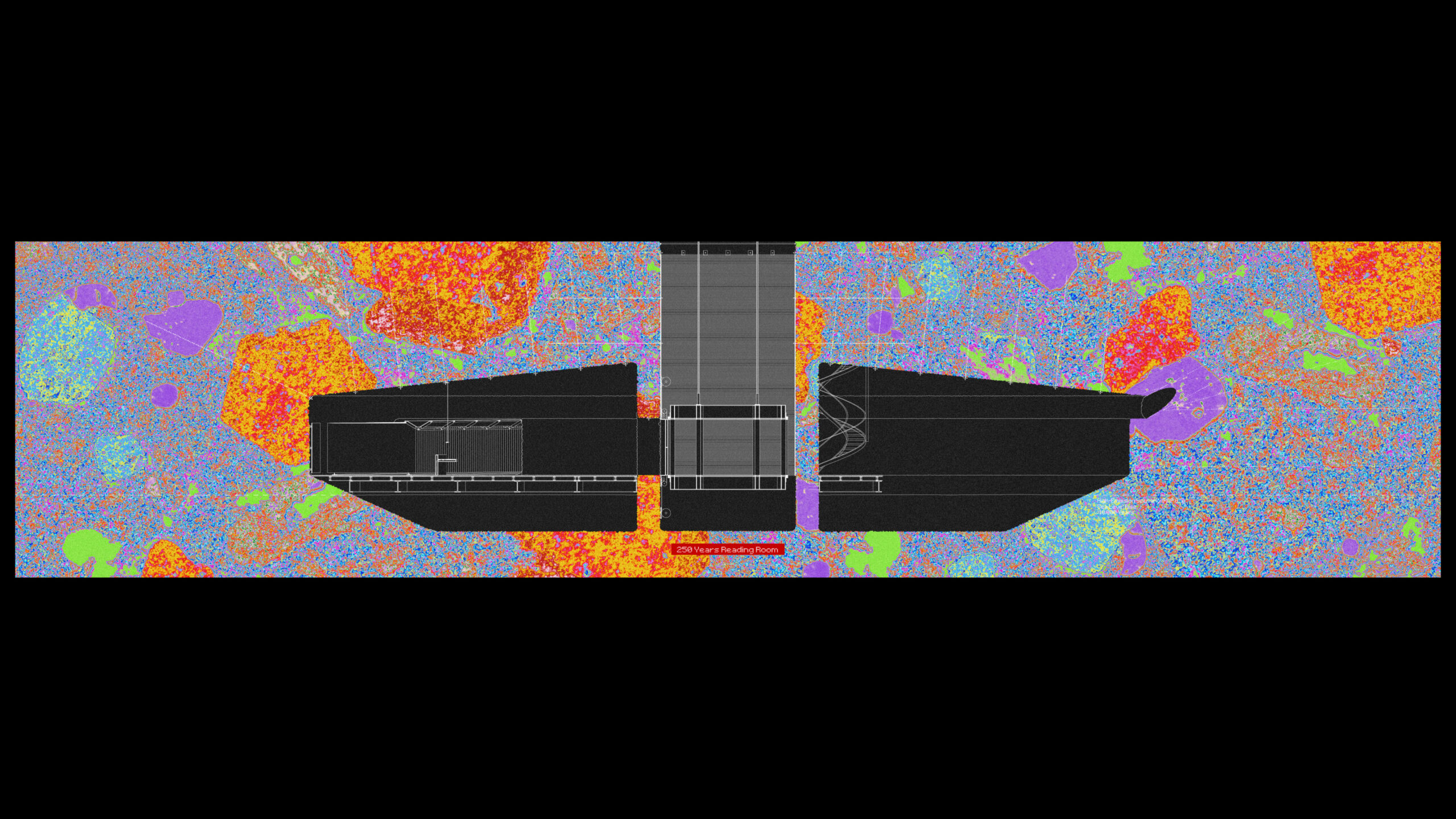

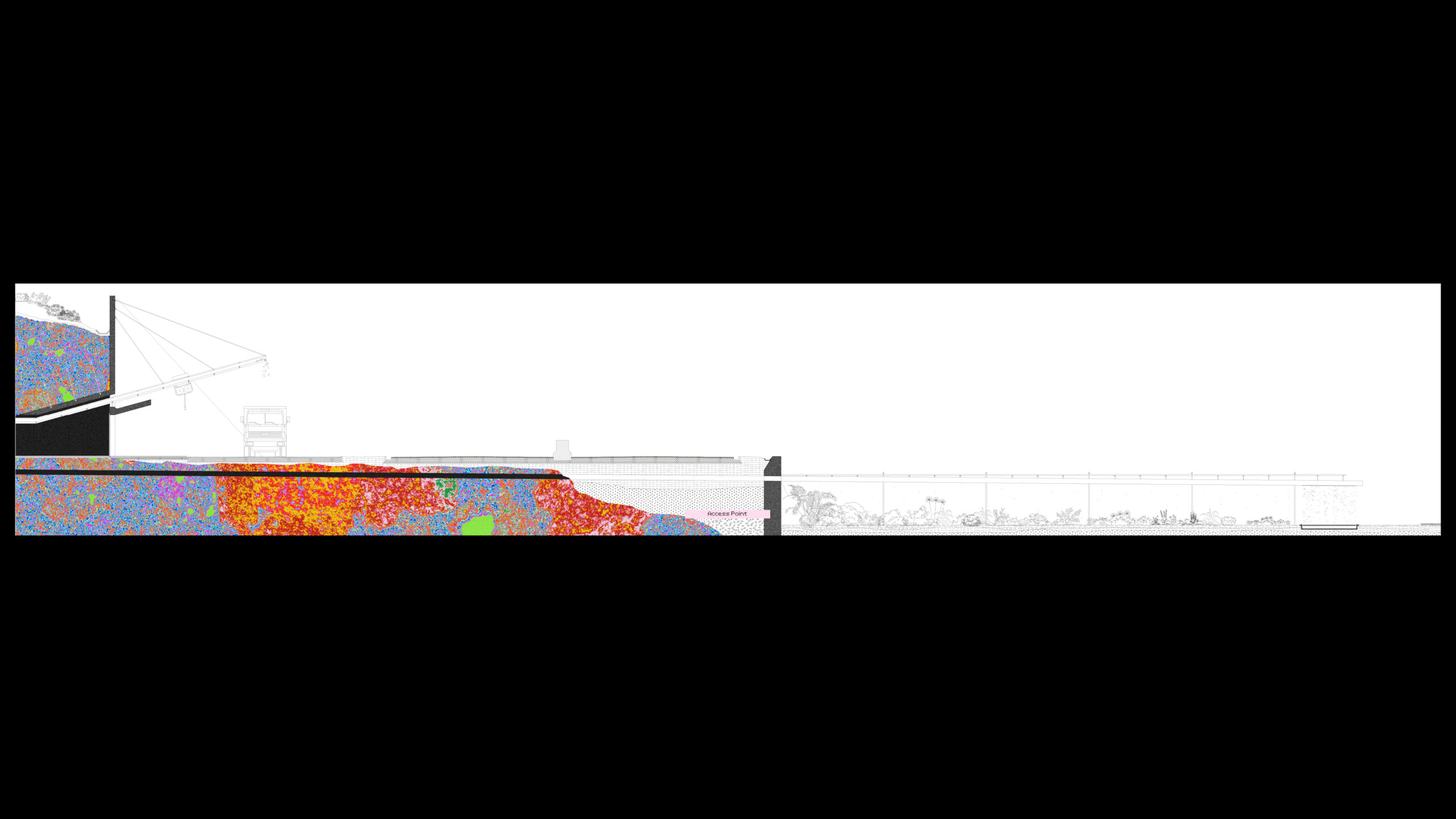

Starting from the existing situation, the SOUTHCOM bunker is to be re-purposed as the secure online layer of the archive. From this point on, in the first year, excavation work is to be completed setting up the main functional elements of the institution. An access tunnel is constructed from the access point on the Panamerican Highway whereby the mobile miner machine makes a loop towards the bunker, scratching its surface, circumscribing the later Room of Passing. Vertical shafts for circulation and ventilation are excavated from the top of the hill, with Reading Rooms constructed at the depths of 15, 69 and 250 years. From this point on, the continuous excavation of the Archive storage tunnels can begin. Given the annual excavation cap and the tunnel profile, the speed of excavation is set at 14.8m per year. From the Room of Passing, the machine dips down in a loop, arriving back to the first Reading Room at the depth of 15 years. Then, a second loop is spun, re-connecting with the vertical shafts at the Reading Room of 69 years. The size and extent of the loops is determined by the available topography of the hill, itself significantly altered by previous extractive operations, thus inscribing the material conditions of the context into the operational temporalities of the institution. Eventually, the final, long-term loop is completed, arriving in the last and deepest Reading Room at the depth of 250 years.

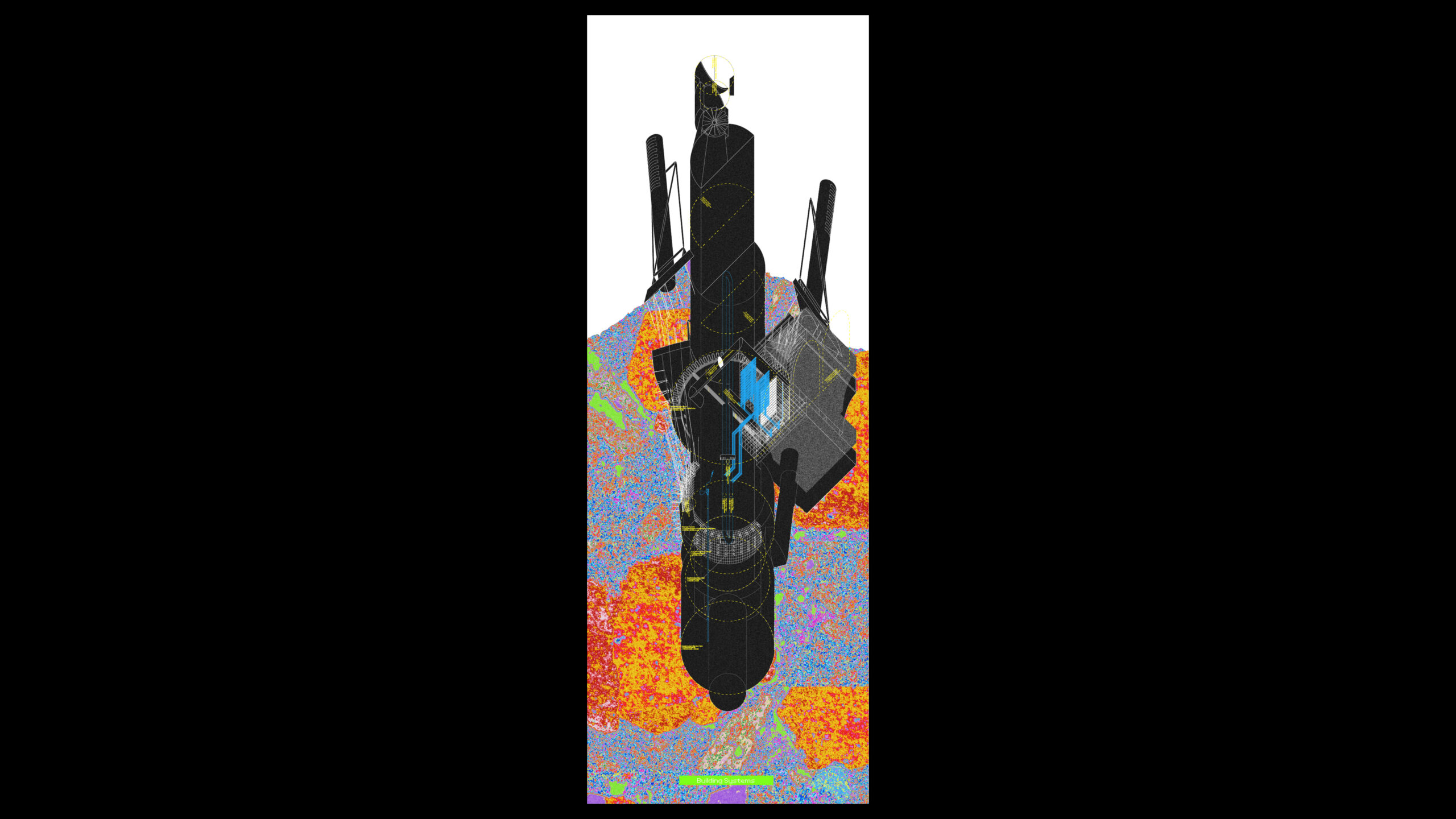

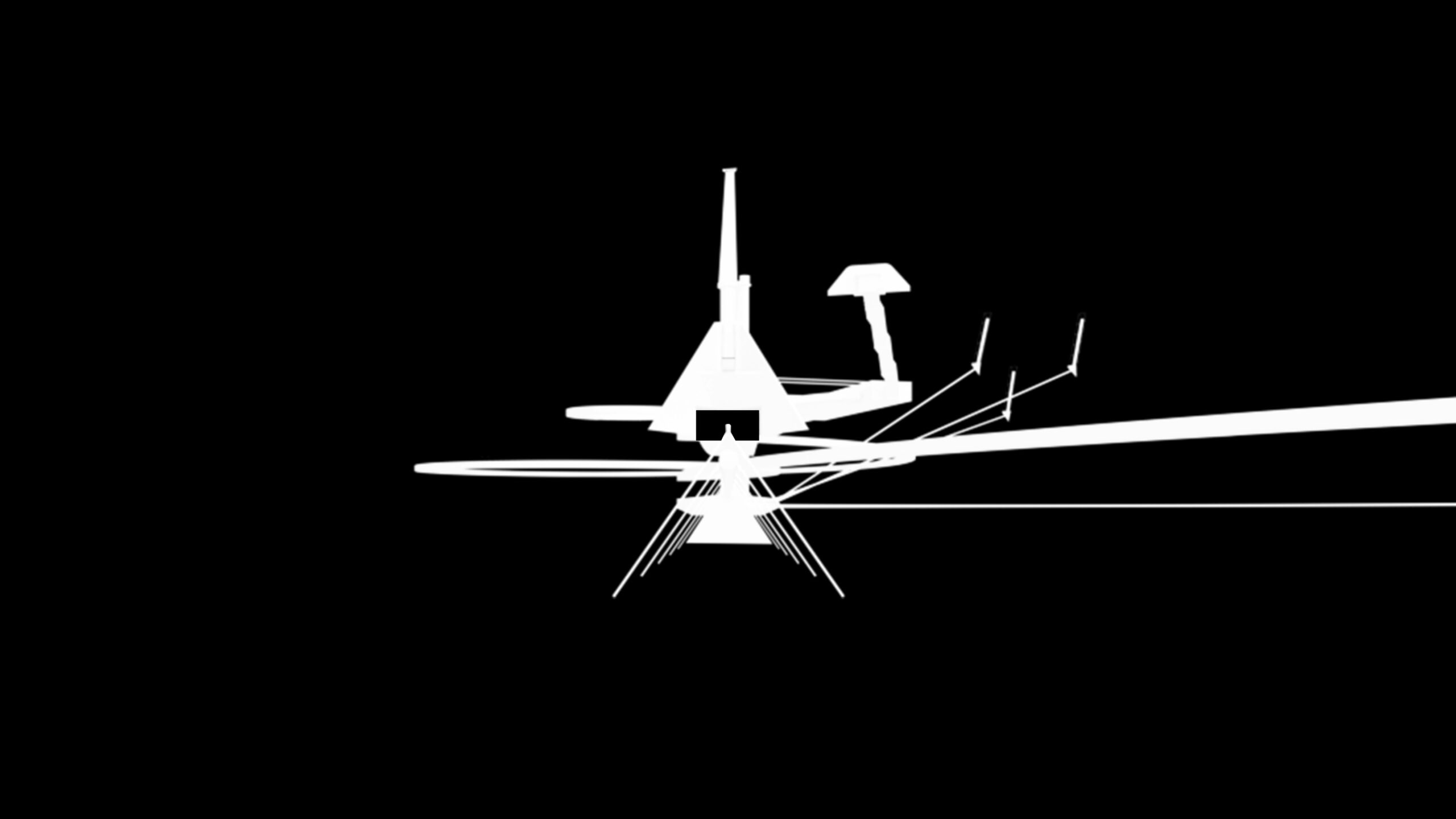

Despite its expanse below ground, the Archive leaves only a handful of traces on the surface – the wind tower and ventilation shafts – which complement the existing assemblage on the hill, while being located exclusively in sections previously scarred by the quarry.

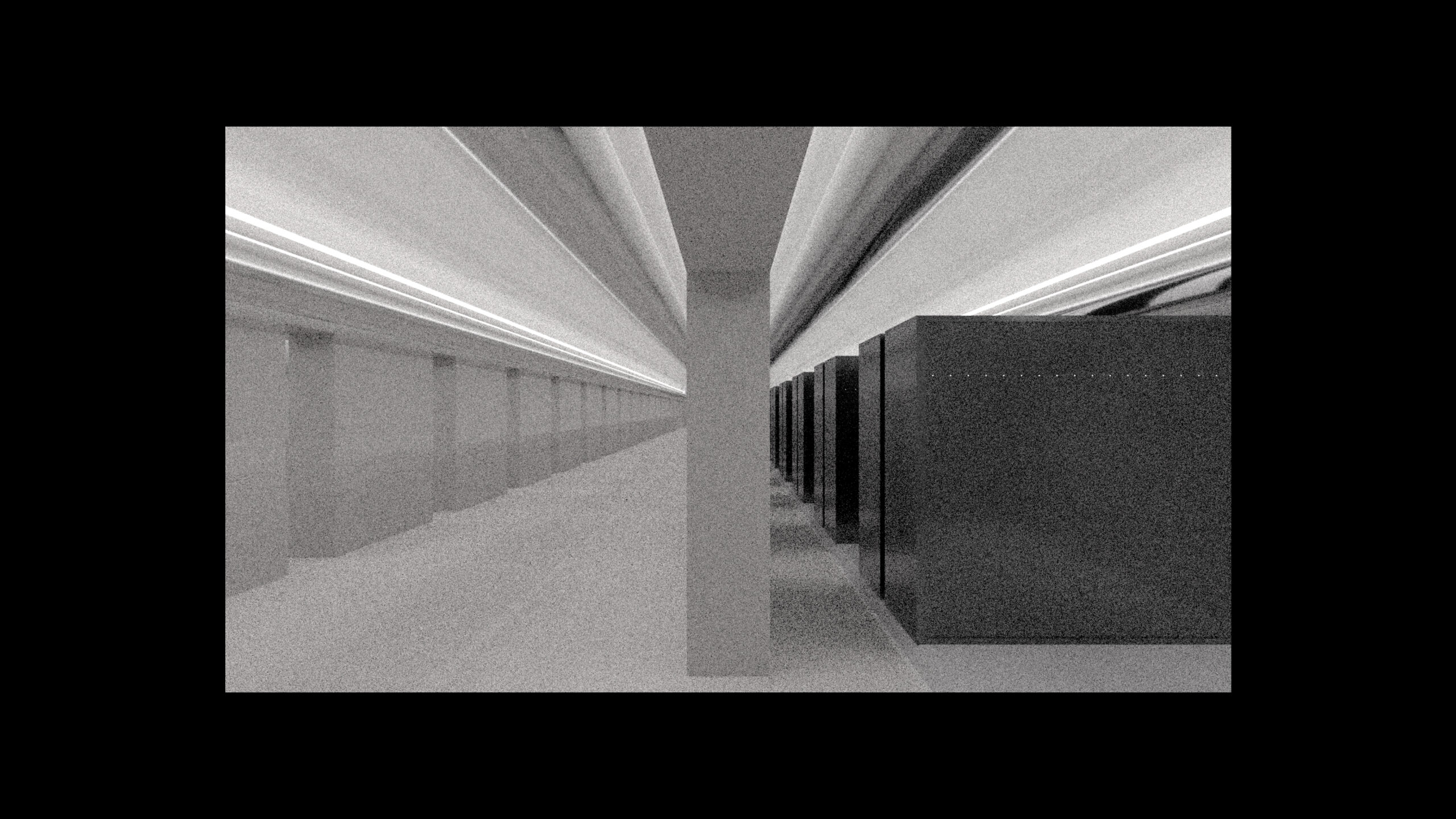

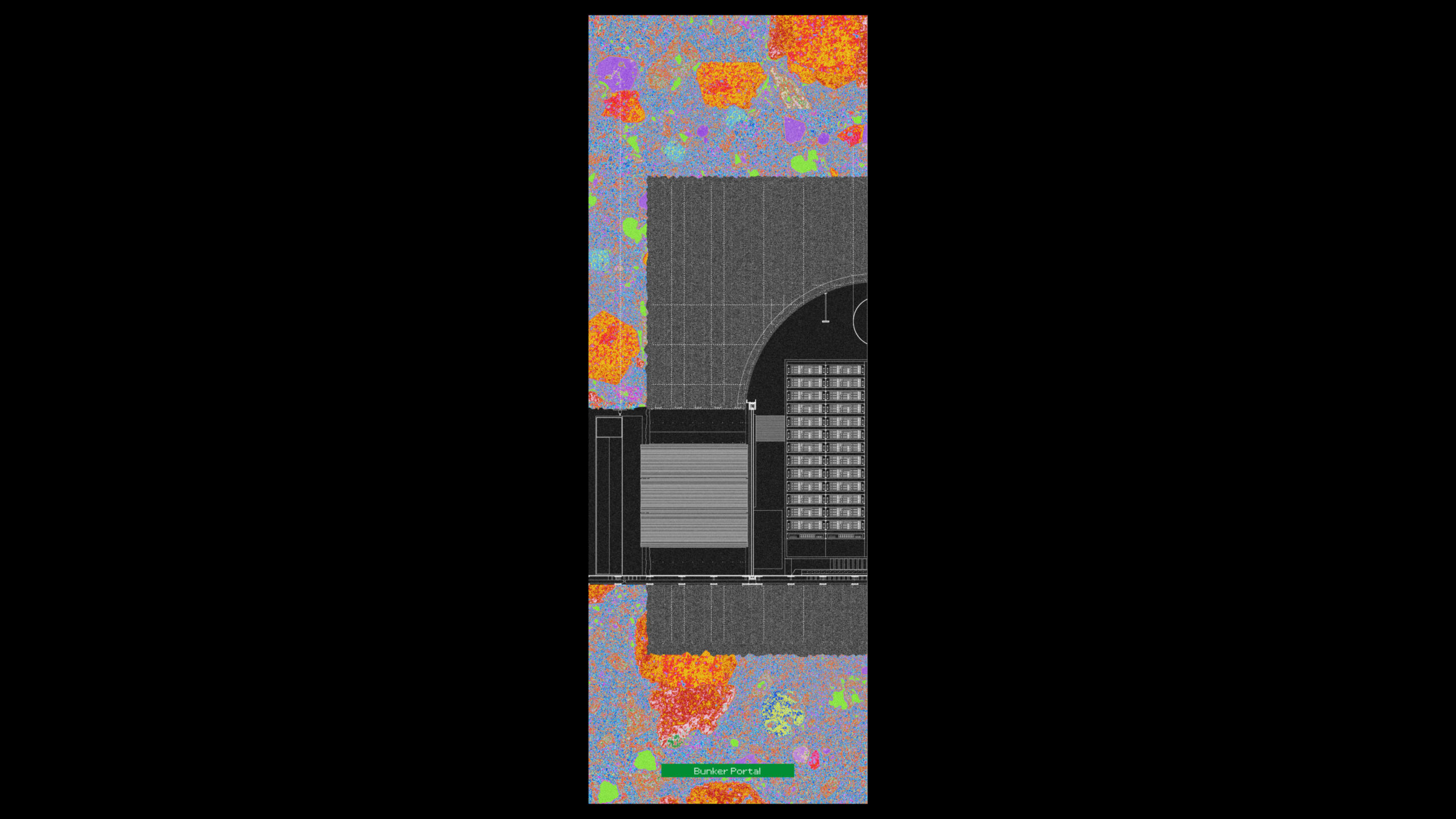

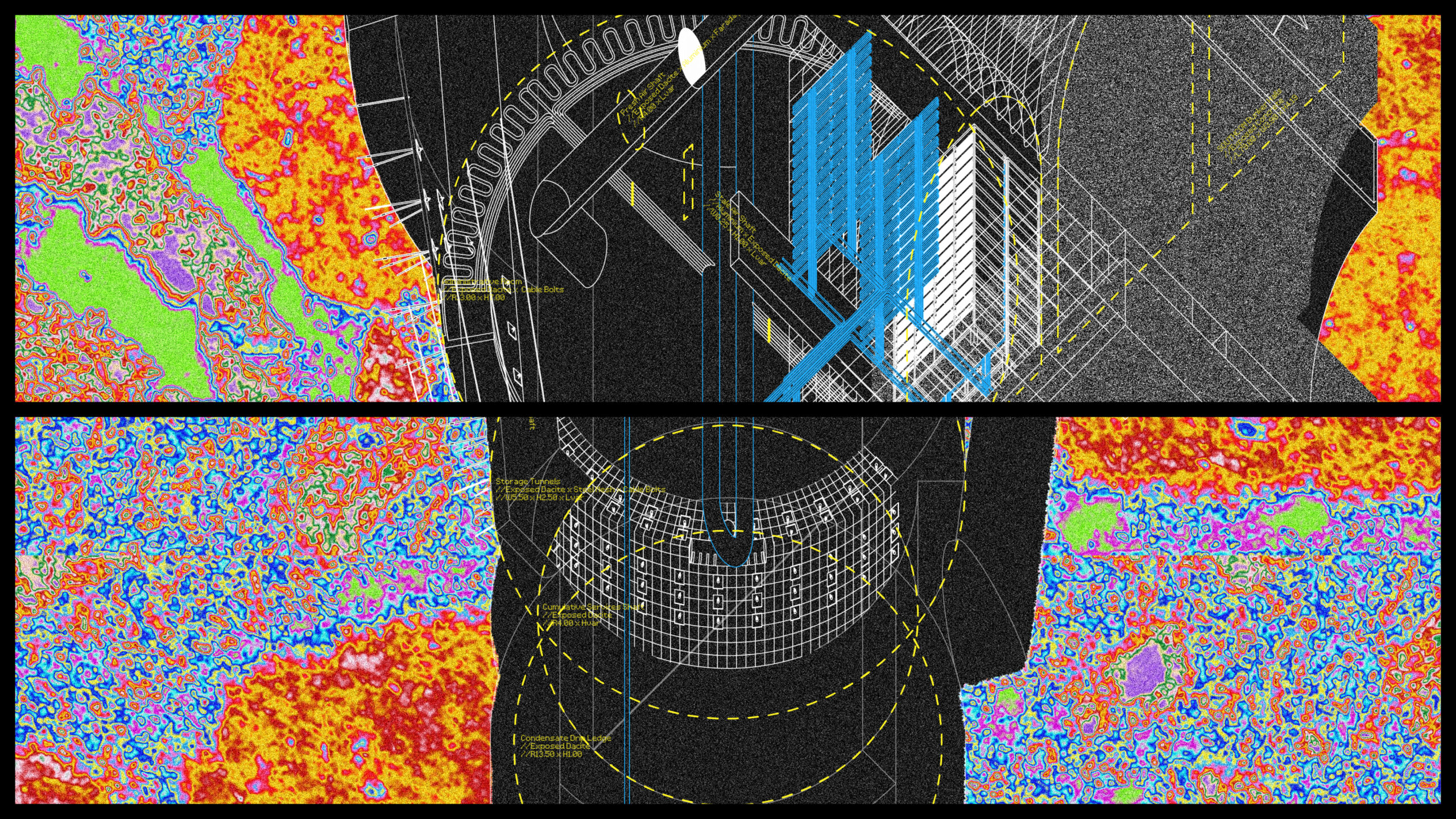

Moving through the Archive, one starts with the former bunker which now becomes the home to server racks, securely shielded from possible impacts and particularly potential Electromagnetic Pulses (EMI)[36] by the faraday cage created through the rebar in the bunker’s shell.

The bunker connects to the excavated part through a cut in its shell which as many other parts of the structure is determined by its construction technique – in this case drilling.

Through this connection, one arrives in the Room of Passing, where data from the realm of the online, flickering and malleable present passes into the offline, cold and tangible past. Here, decisions on procedures, protocols and contents of preservation are being discussed and determined. At the same time, just behind the plenary space, consciously presented as its focal point, sits the production table where data from the online archive is written onto media that is to go down into the storage. In this way, decision-making and production are not relegated to separate domains but rather co-exist and contaminate each other’s operation.

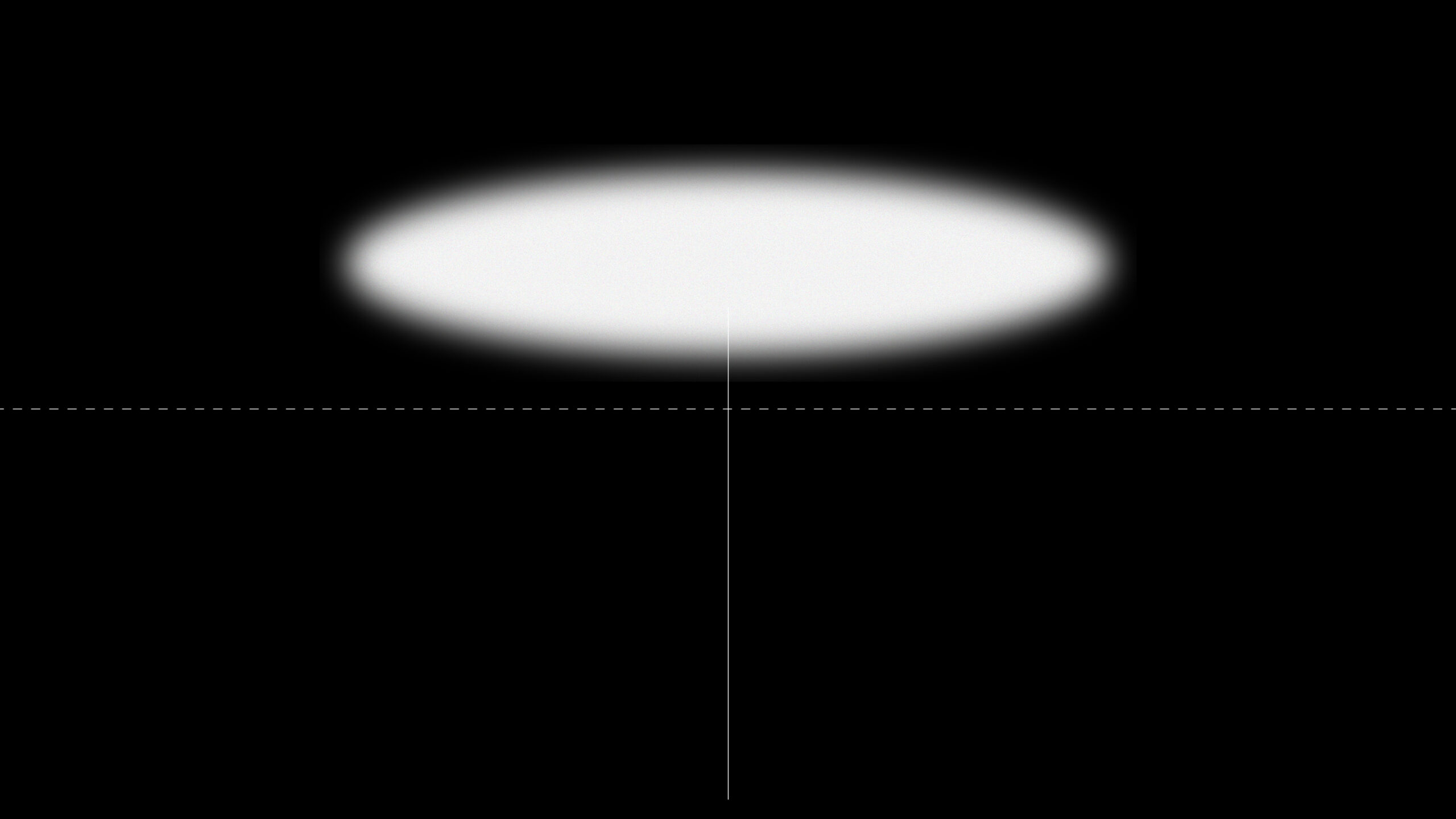

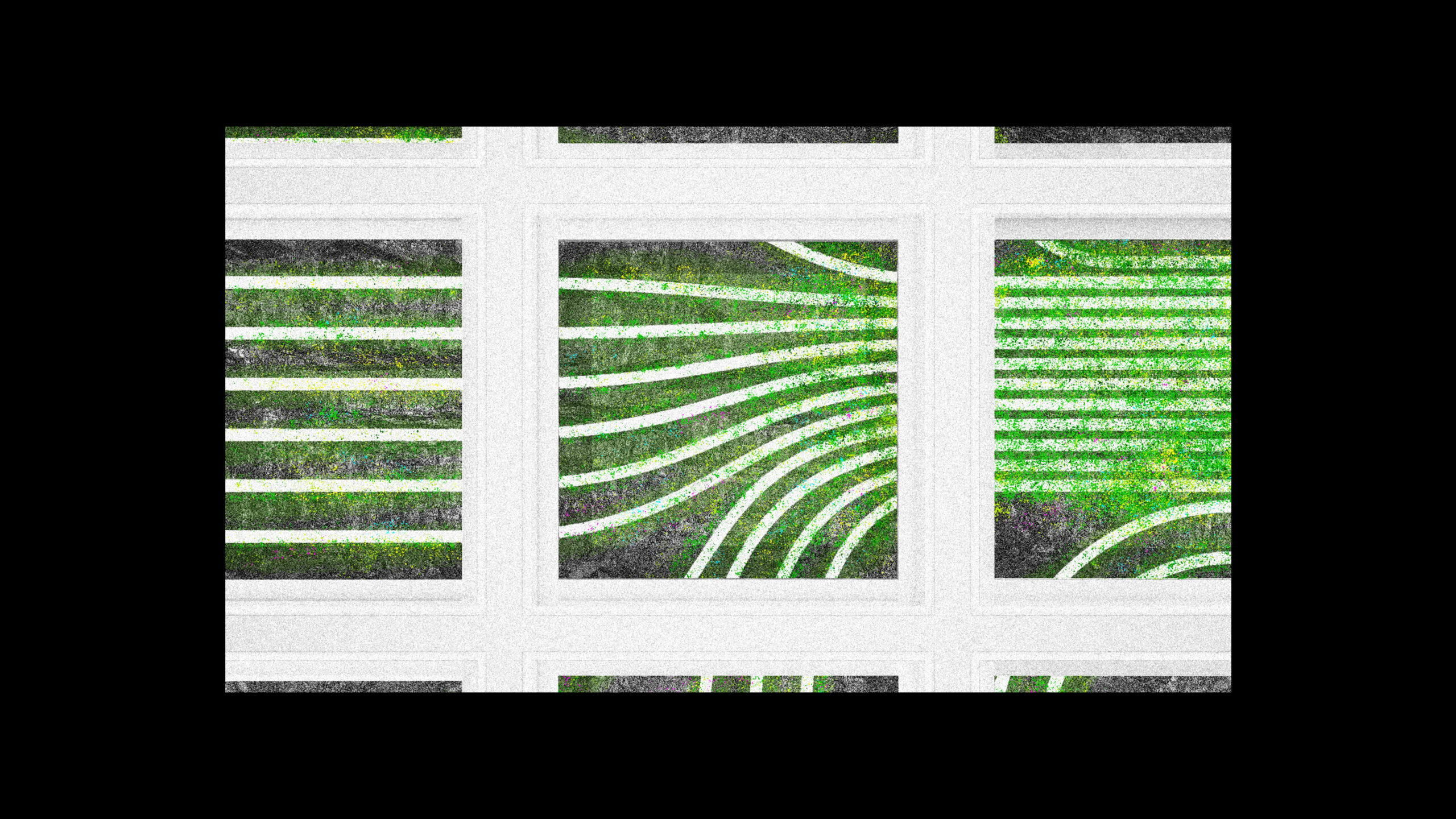

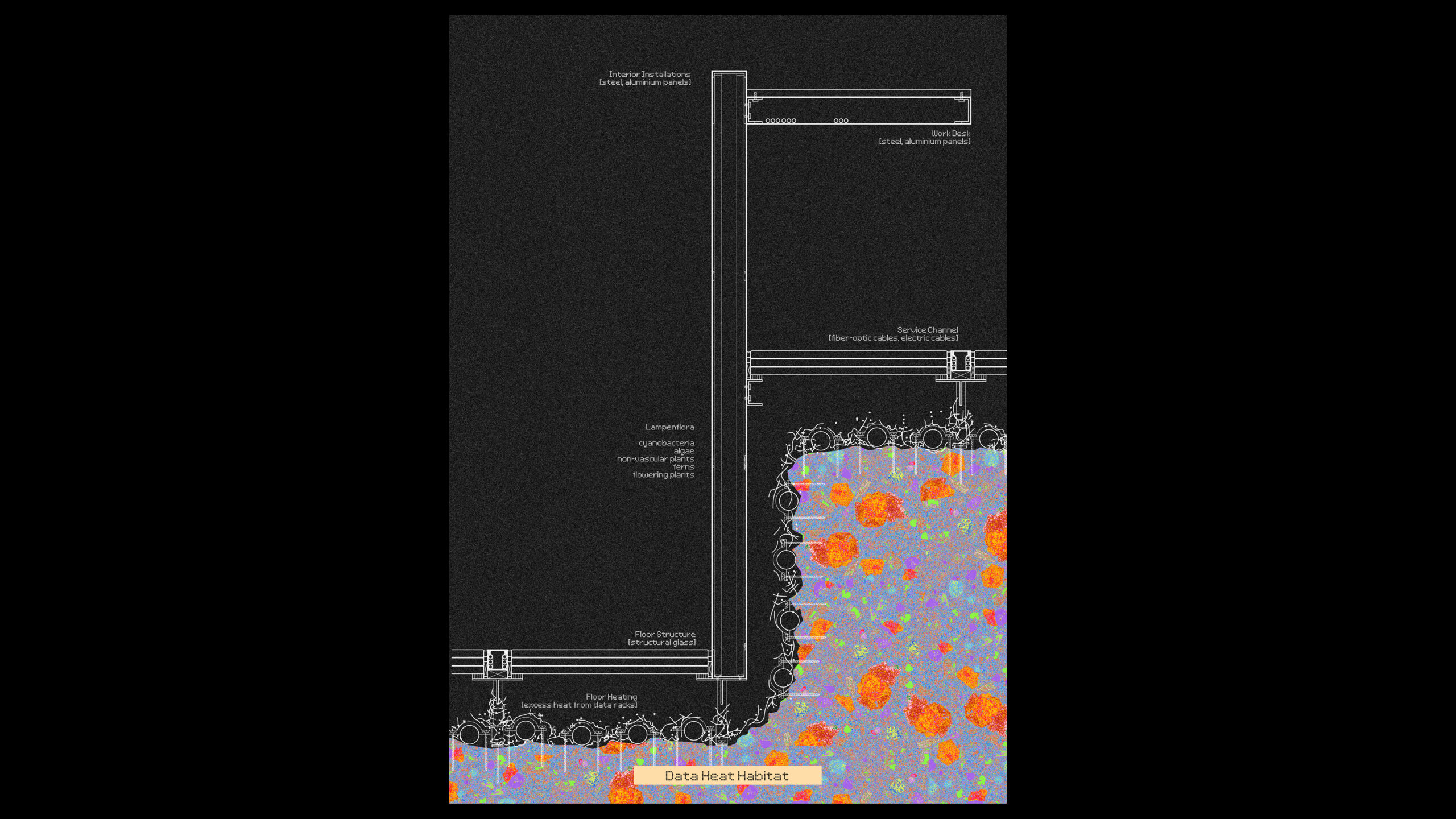

As the cold rock floor of the Room of Passing is used to cool the server racks inside the bunker, excess heat and constant light will become breeding ground for a phenomenon called Lampenflora. Algae, cyanobacteria, moss and other organisms will flourish on warm, lit rock surfaces. While commonly countered by preventive measures, here it is to be cared for and exposed beneath a glass floor, highlighting the entanglement and co-production of digital infrastructures and biological systems.

The storage tunnels starting from the Room of Passing, are being continuously excavated by a mobile miner machine, with canisters filled with data sliding down behind it. The storage rate, coupled with the excavation rate, amounts to 2 million petabytes per year, using optical discs as the medium of storage for the initial phase of operation.

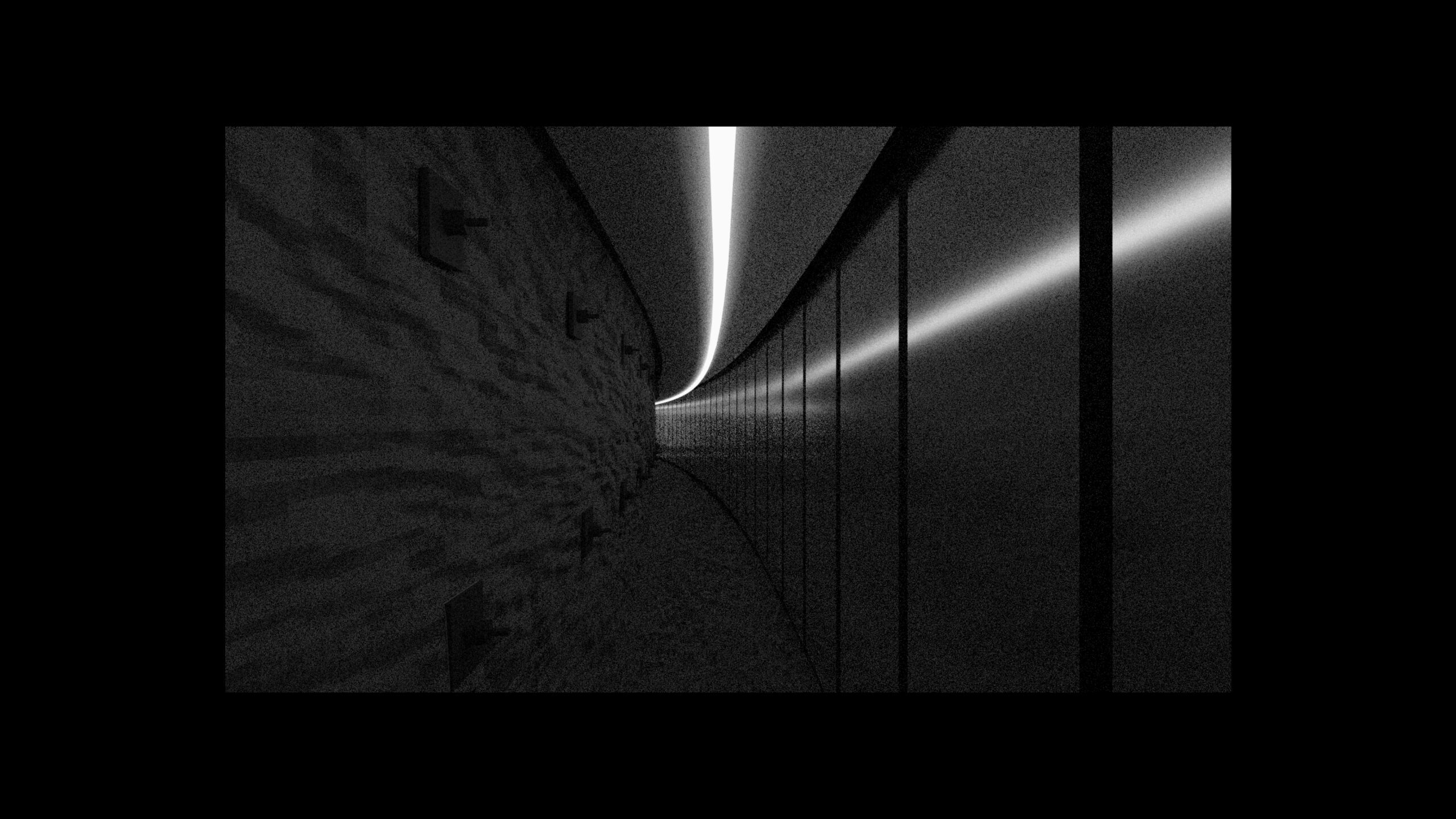

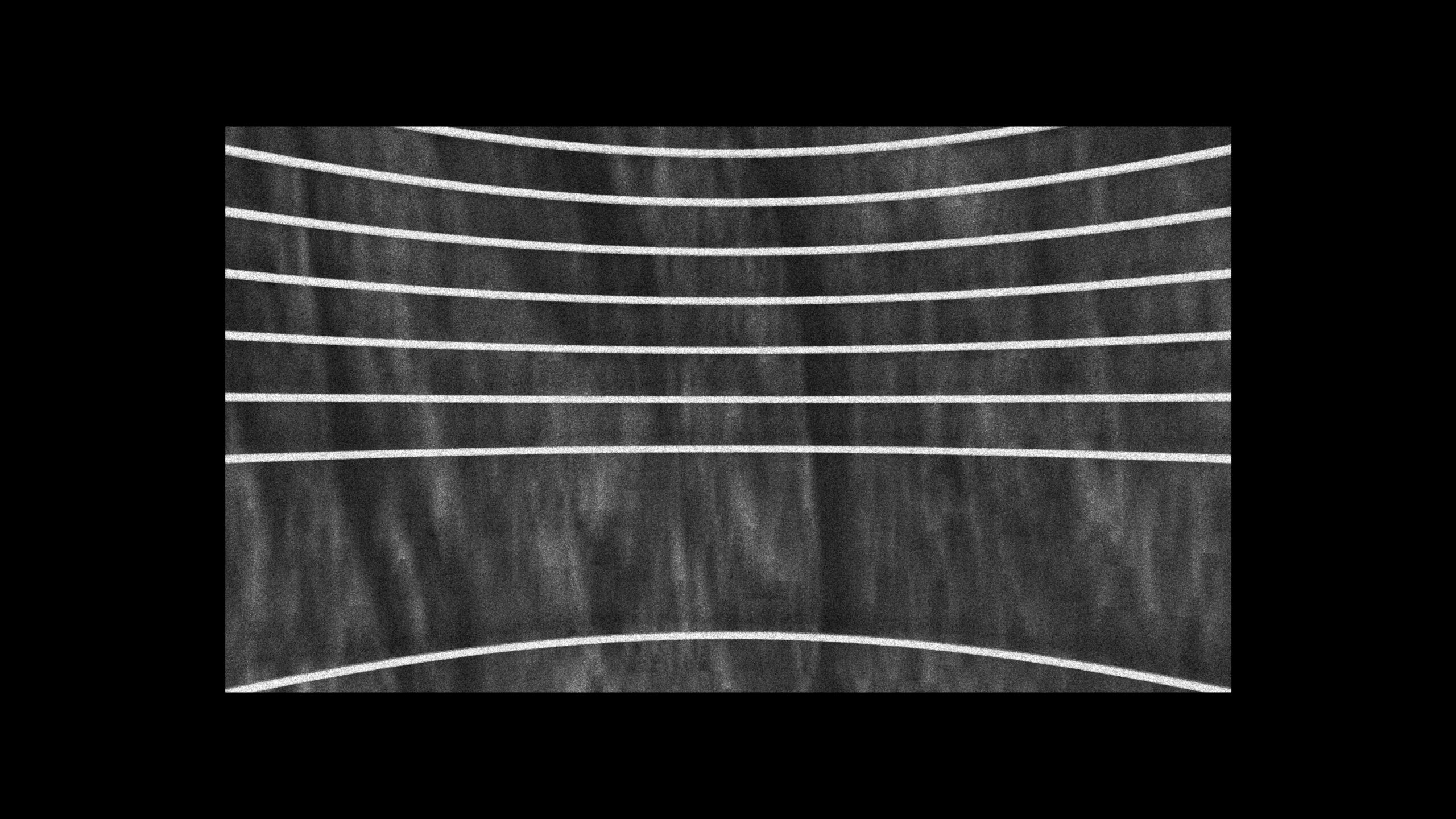

In the main lift shaft, as the length of tunnels relates to years one travels through the archive, lights are mounted corresponding to years and depth passed on the journey through the shaft, spatialising the temporal relations within the institution.

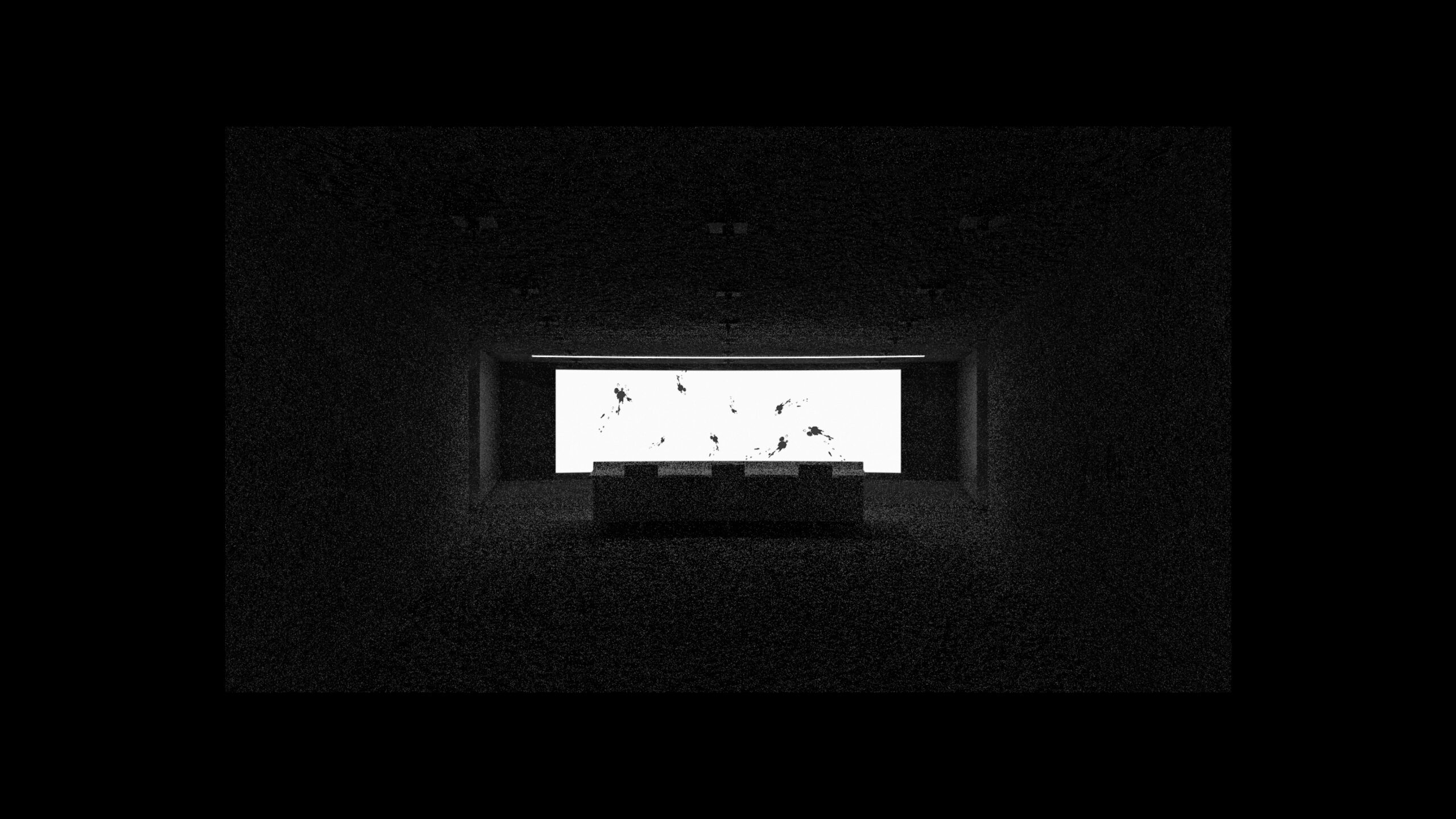

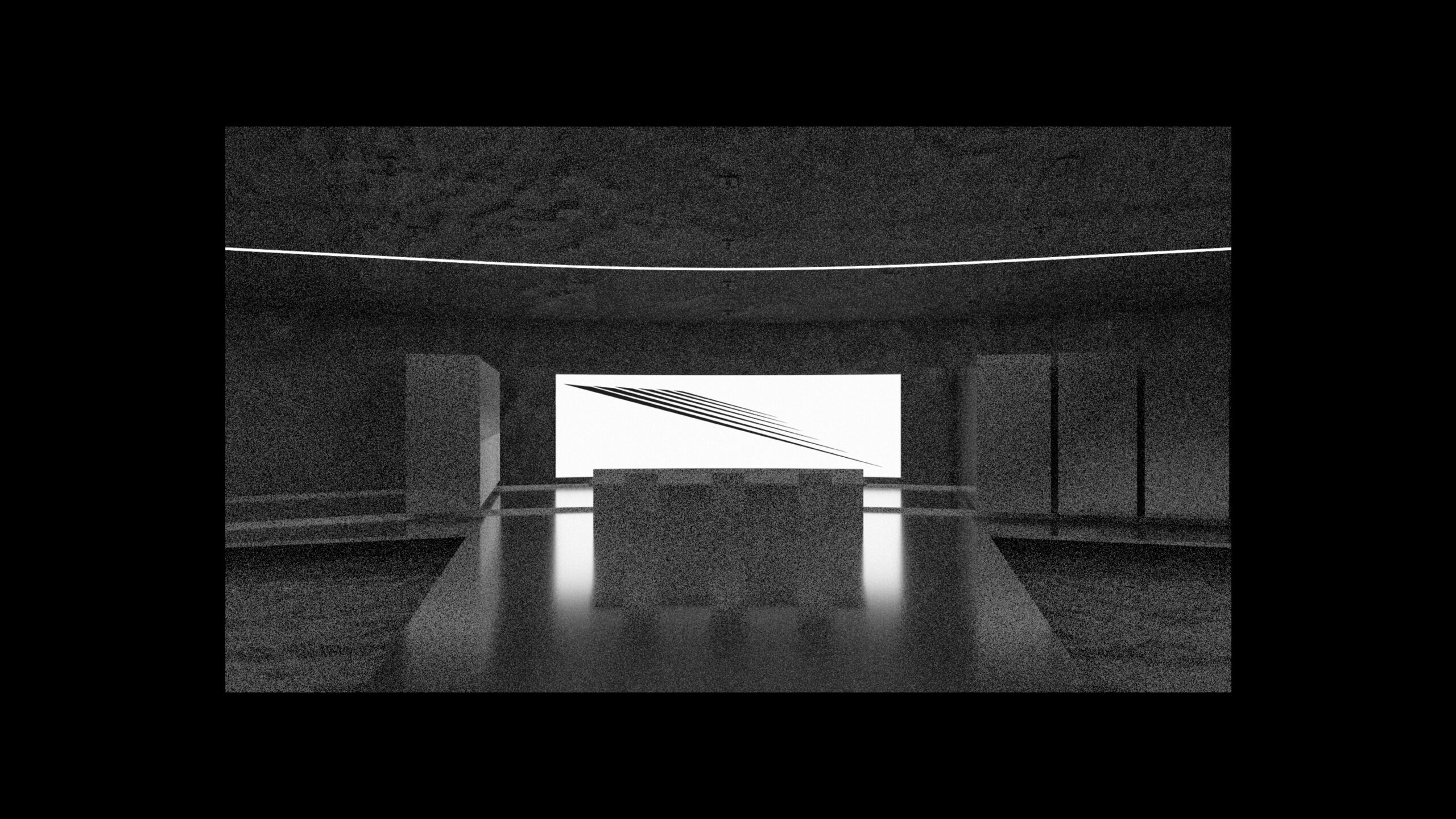

Located at points at which the loops swing back from their oscillations, the Reading Rooms present moments of critical engagement and inspection of content stored 15, 69 and 250 years ago.

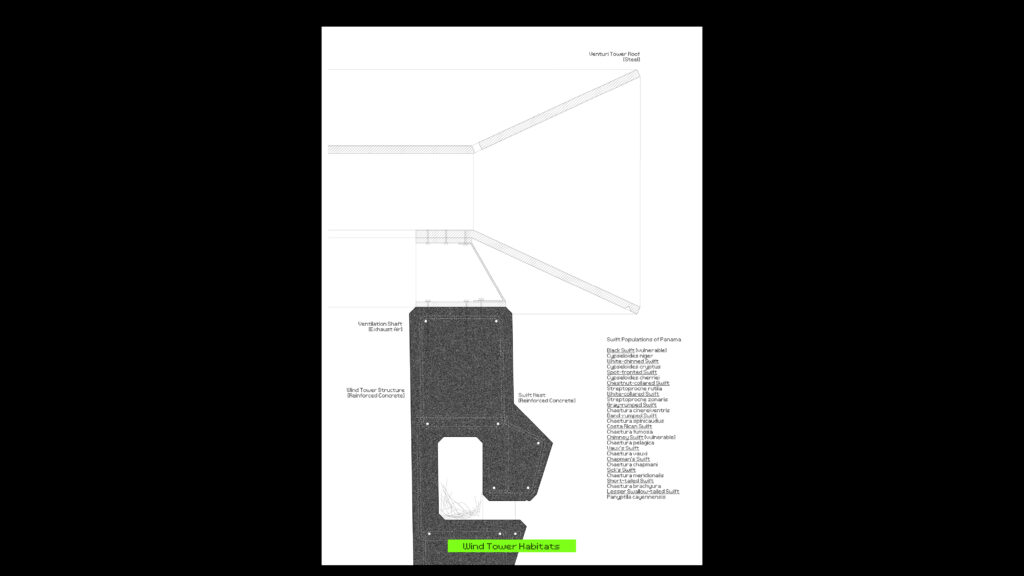

The building systems are consciously intertwined with the geological condition. For instance, low temperatures of the rock surface are cooling the server racks as well as the fresh air drawn in to ventilate the underground spaces. Traveling through the ventilation shafts that face the main wind direction, the hot and humid air cools down – condensing into water on the rock surfaces, trickling down to be collected in a basin at the bottom of the structure. Complementary to it, the Venturi Roof at the top of the wind tower creates a continuous draft, aiding the removal of exhaust air as well as the intake of fresh air, completing the cycle. Through the enmeshment of archival systems with geological and climatic conditions, the storage capacity and operation of the archive start to become readable through a variety of material flows and media.

Sitting at the lowest point of the archive, the third and last Reading Room is a space for re-examination of content placed into the storage 250 years ago. Once the shelves descend all the way down, they are emptied and read, ascending back up for re-negotiation of repeated archival or fall into oblivion. Furthermore, the Reading Room is where the water condensing from the ventilation shafts fills a basin that sits at the elevation of a 25 metres sea-level rise prediction for a high-emission scenario, currently estimated to be achieved in 10.000 years. [37] In this way, the archive, located above that remains safe for at least this period of time.

While the Archive is a leviathan underground, its moments of surfacing are rather delicate. For instance, at the access point, where excavated rock leaves the hill, a fountain carrying overflow water, condensed inside the Archive, comes up to nourish life, where once the former well provided water to the people. The wind tower, at the same time, houses a habitat for swifts, a locally endangered bird species that depend on Ancon Hill as a critical island of biodiversity among expanding urban sprawl.