PANAMA CANAL ZONE

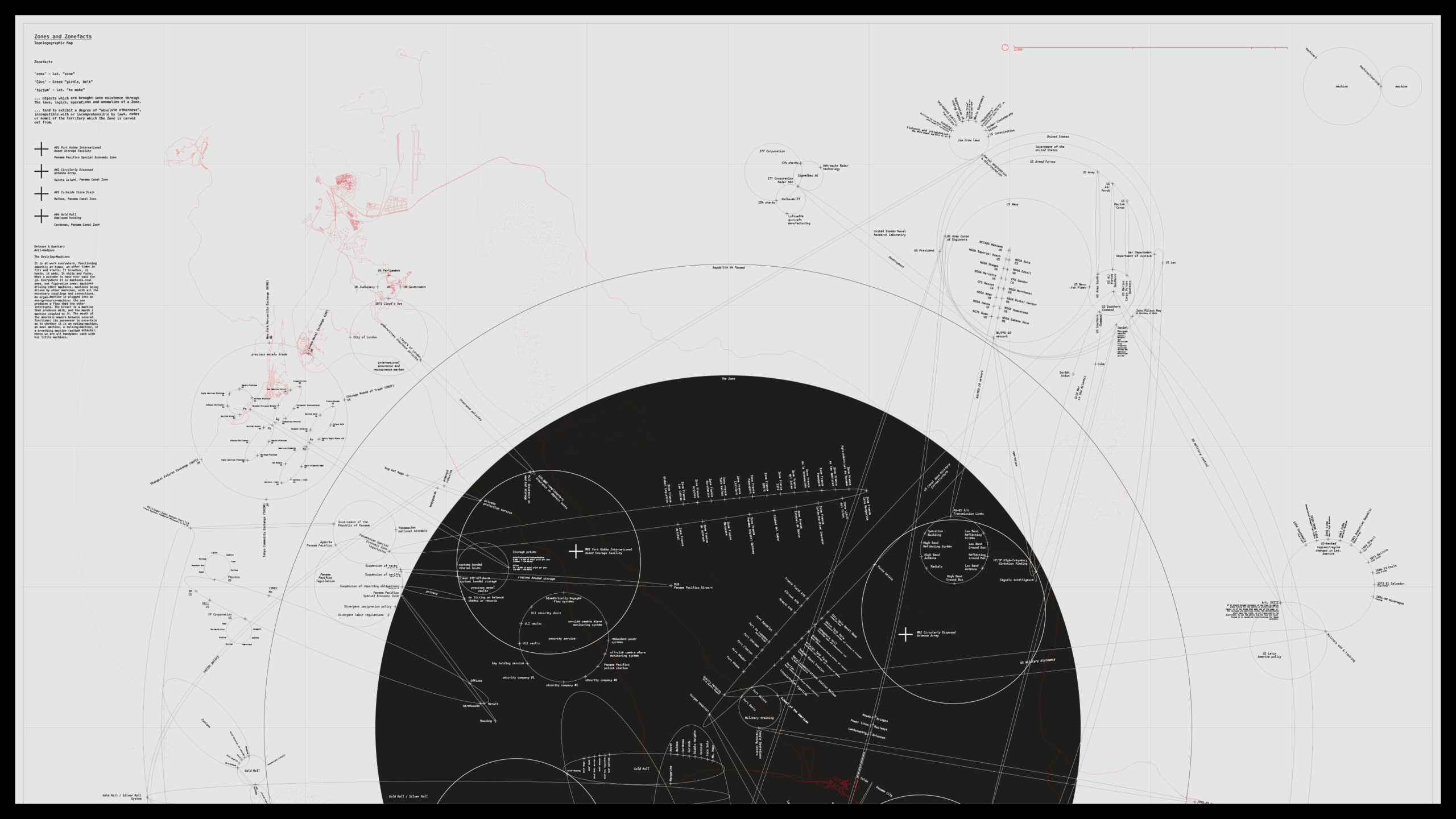

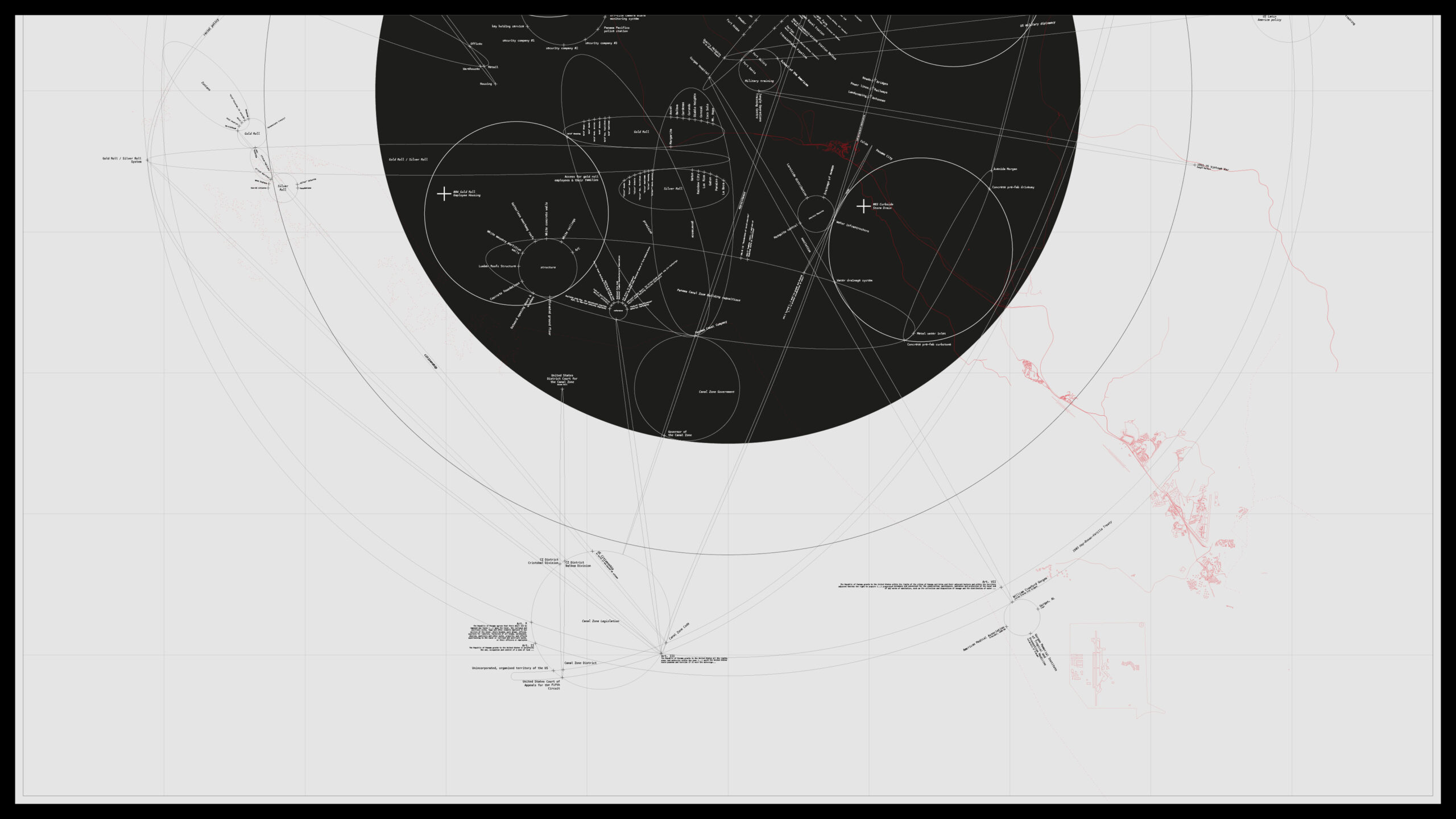

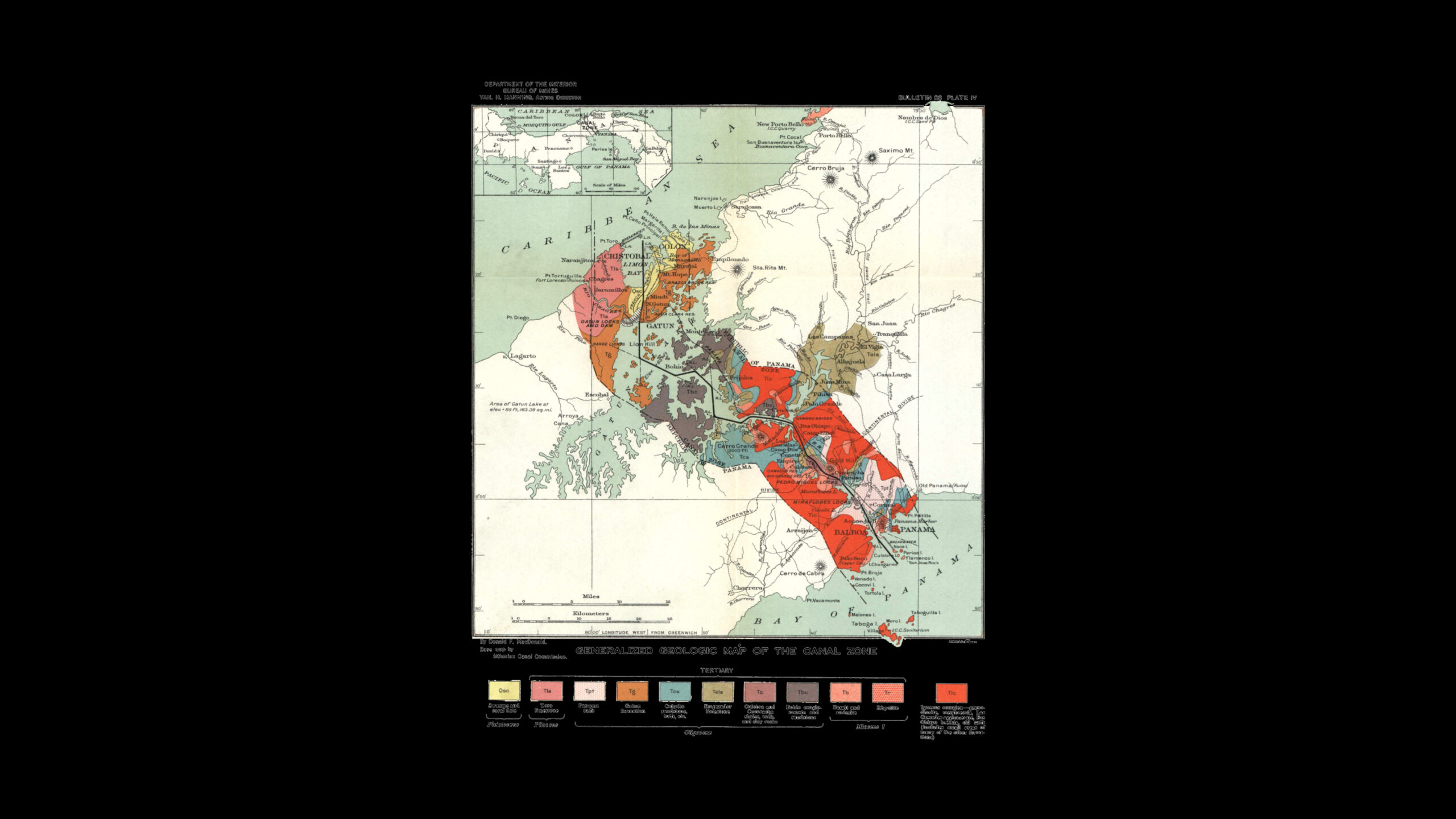

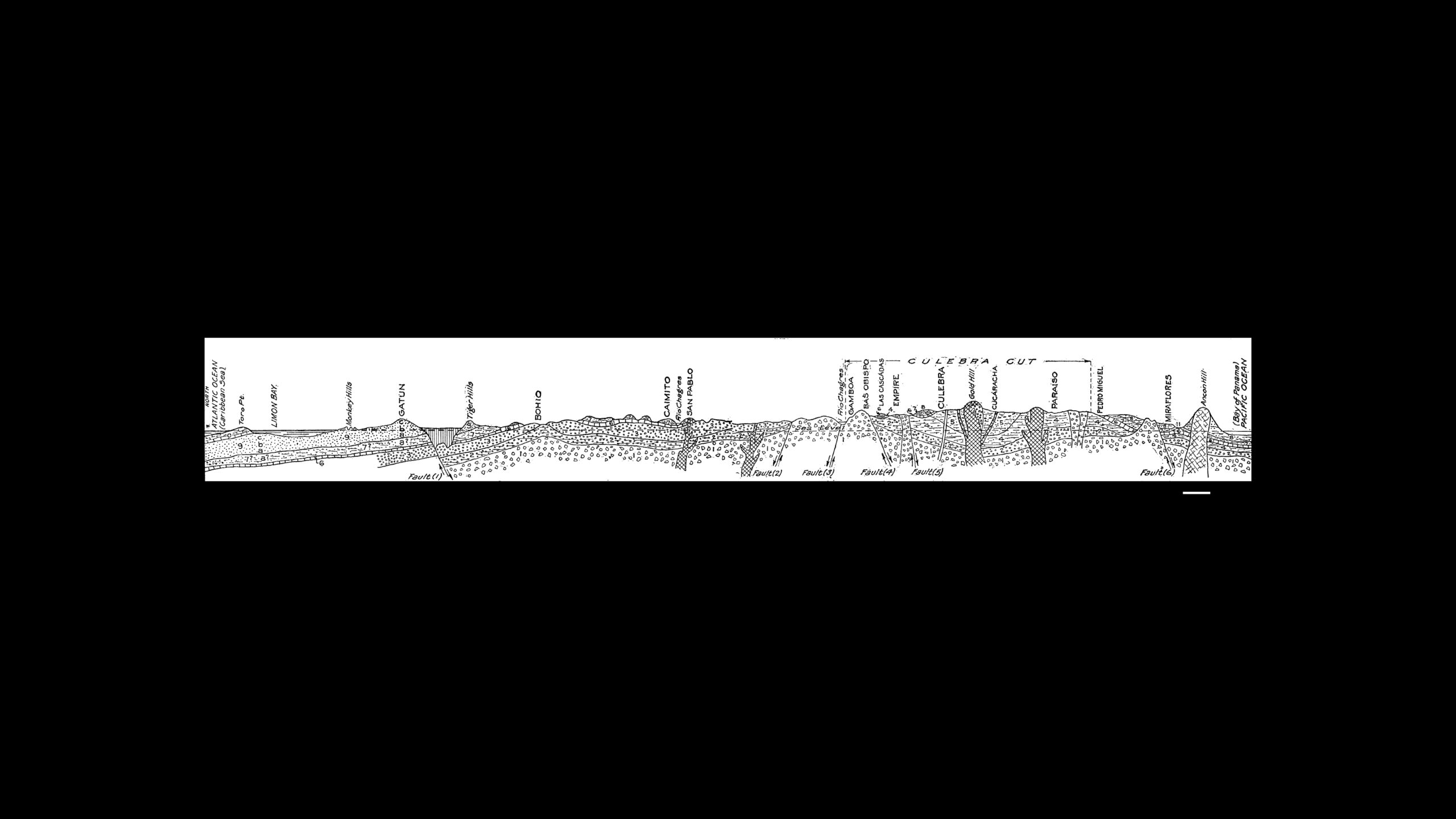

Beyond the political and conceptual significance outlined above, the Panama Canal Zone – a stretch of land largely defined by an offset from the navigational line of the Panama Canal by 8 kilometres – is problematised as an infrastructural issue from the outset. It is an almost diagrammatic application of cartographic abstractions onto a territorial reality which inevitably collides with a series of obstacles that challenge its idealised geometry. In order to accommodate the resulting tension and produce a reliable and controllable space, it relied heavily on a system of strategically developed and complementary infrastructures around which life in the Zone was organised.

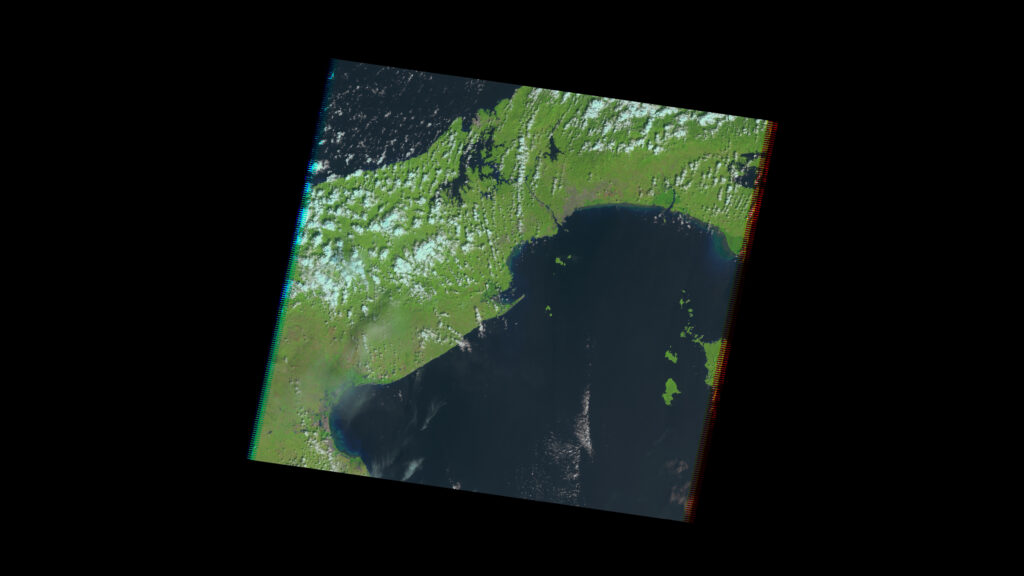

Legible from space as a strip of strikingly lush forest amidst expanding urban landscapes, today, the roughly 60 kilometre stretch of land that separates the Atlantic from the Pacifc ocean at its narrowest point is dotted with remnants of the former Canal Zone. While some of them become modern ruins, slowly absorbed by the rainforest, others undergo curious transformations that adapt them to a post-militarstic reality. Forts and airfields at both sides of the entrances to the Canal; training grounds for the School of the Americas[27] on the shores of Lake Gatun; radar stations rising the dense tree canopy; countless barracks, towns, shooting ranges, hangars to house the military and civilian personnel alike; but also roads, railways and pipelines criss-crossing the territory are all traces of a world that is no more – and yet so ever present.

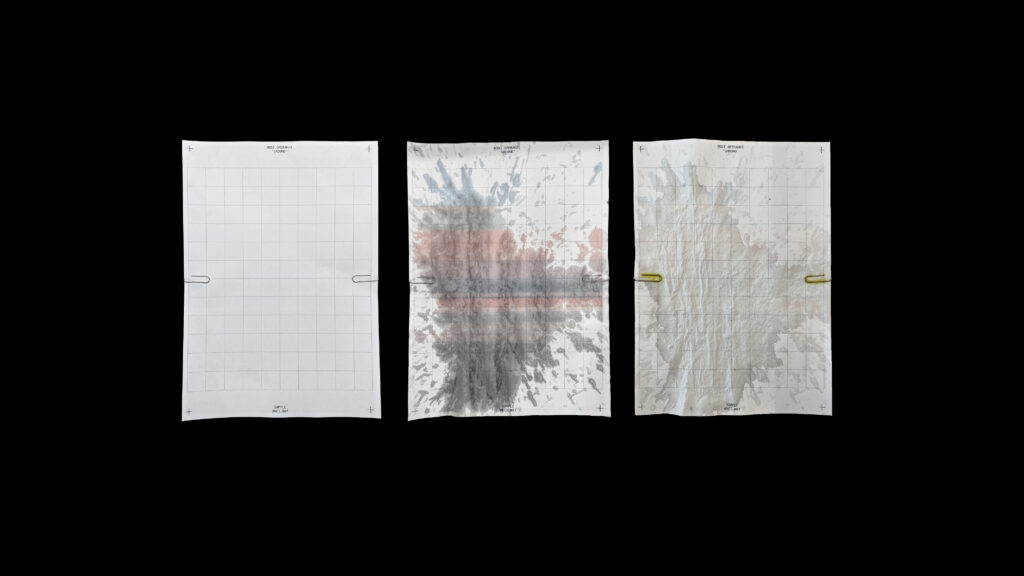

With the Zonian community mostly repatriated to the contiguous United States and US military withdrawn outside of the newly (fully) sovereign Republic of Panama, it becomes more difficult to interpret the modi operandi of the territory fundamtentally structured by forces no longer present. To address this, as suggested above, it becomes generative and insightful to examine the implications of the Zone through engaging with its spatial products and the relationships which they form. This way, a close reading of only a handful of objects produced by the workings of the Zone can reveal a lot about the operational complexities involved in their establishment and maintenance. In this way objects such as an International Asset Storage Vault located in one of Panama’s Free Trade Zones, established in a former air force base, reveals a lot about special tax and legal regimes, entanglement with international insurance and precious metal market. An abandoned circular antenna array surrounded by mangroves on the coast ties in with global military logistics of surveillance and information gathering as part of a larger Cold War effort on planetary control. Something as seemingly banal as a curb-side storm drain, through its adherence to specific imported standards becomes an entry point to colonial ideologies of ‘civilising missions’, while the ruins of former ‘Gold Roll’ employee housing unpacks complex politics of racial segregation and control.

Looking closely, one starts to see how the appearance of a Zone reveals its underlying logic by means of its spatial products. Having erupted, introducing an otherness in the immediate sense, over time and past its actual operation, it re-shapes the ground in which it landed, bringing a new topography into the territory, organised by and around the objects it has produced. The paradigmatic eruption of absolute otherness, elaborated above, then becomes a productive conceptual framework through which such an investigation can take shape.

Following such a notion both literally and metaphorically, one place clearly stands out that is both home to many zonefacts – products of eruption – as well as being one itself – Ancon Hill.