DEFINING THE TERRITORY

The fundamental aim of architecture is to define intentional boundaries, shaping space against an apparently chaotic backdrop. It is, at its core, a practice concerned with imposing order, mediating the relationship between human intervention and the natural environment. With the introduction of the term urbanization, Ildefonso Cerdá introduced a paradigm shift in spatial thinking, challenging the traditional urban-rural divide, which capitalism had already begun to erode. He states: ‘[capitalism] is a vast swirling ocean of persons, of things, of interests of every sort, of a thousand diverse elements that work in permanent reciprocity and thus form a totality that cannot be contained by any previous finite territorial formation such as the city’.[10]

This perspective encourages a broader conceptualization of space, shifting from a geographically defined landscape to one that is volumetric — a complex assemblage of political, ecological and ethnographic forces constantly in tension. The landscape, therefore, is not static; it exists in a state of flux across different scales and temporalities.

Pier Vittorio Aureli expands on this idea, arguing that urbanization has fundamentally blurred previous spatial and social dualities: ‘[urbanization] has blurred for good some of the dualities upon which previous subjects built their world, first and foremost the distinction between public and private, and, subsequently, the triad labor-work-vita active. Oppositions between work and otium, private and public, inside and outside cease to have any meaning, as the spaces we live in become increasingly hard to label as belonging to one definite sphere: work mingles with living, private with public, production with reproduction’.[11] In this view, the landscape is an abstraction — both a symptom of artificiality and capitalism. It consists of forms with indeterminate and adaptable content, where abstraction holds an aesthetic quality — a promise of imagination and malleability.

If abstract landscapes are a fusion of multiple volumetric entities, their ability to transform and evolve must also be acknowledged. More importantly, they should be open to anticipation and participation. Umberto Eco’s concept of the open work supports this perspective: ‘every performance explains the composition but does not exhaust it. Every performance […] offers us a complete and satisfying version of the work, but at the same time makes it incomplete for us, because it cannot simultaneously give all the other artistic solutions which work may admit’.[12] Eco argues that one interpretation should never nullify another. For the purpose of this argument, his reasoning is understood as a proposal for multiple readings of our environment, made possible by simultaneous interpretations.

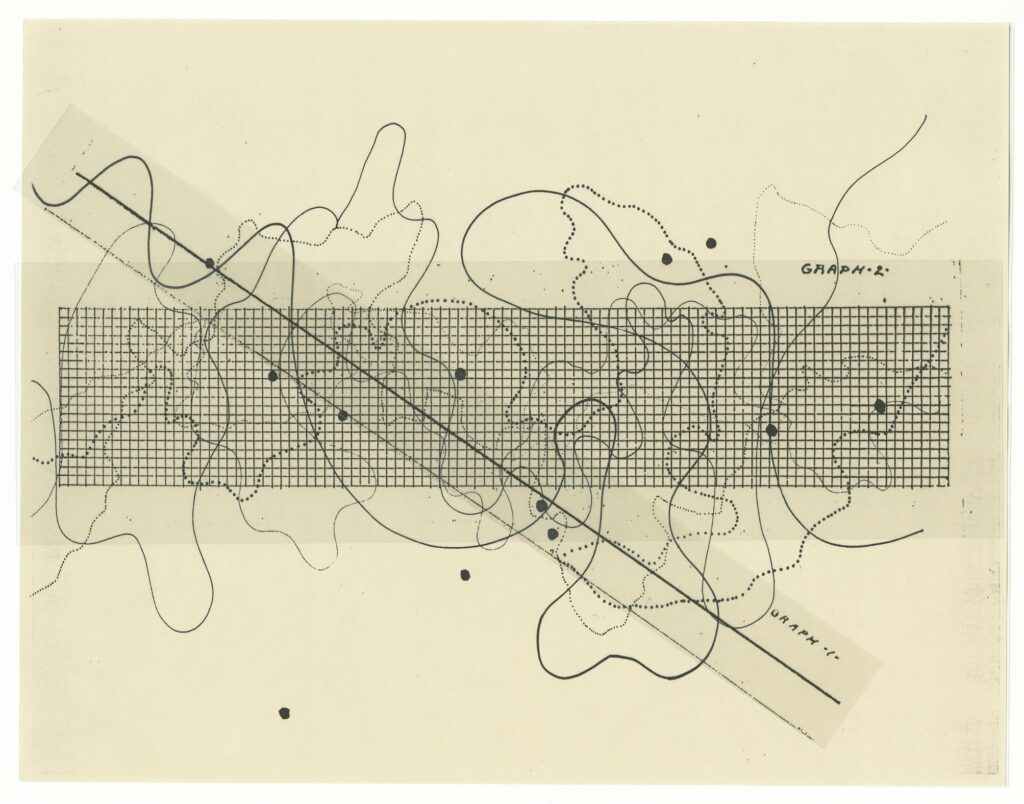

Many of these ideas are already present in contemporary theory and artistic practice. John Cage’s notation systems for musical compositions, for example, were designed to enable ‘the ability of a piece to be performed in substantially different way’.[13] The 1958 illustration for Fontana Mix demonstrates how a single composition could be experienced in multiple ways, shaped by the interactions between performers and the unpredictability of their actions. Silence becomes as important as the produced sound, and the notation relies on performed actions rather than fixed representation. If we extend this analogy to spatial metamorphoses, we can view landscape phenomena as actions — the very essence of territorial practice. Landscapes are not merely objects but dynamic entities, constantly redefined by human and non-human interventions. This perspective aligns with Indeterminacy as a conceptual lens, enabling the identification of specific spatial practices that shape our perception of space. Indeterminacy not only helps dissect complex territorial practices but also reshapes the way we perceive and engage with them. Thus, it is crucial to define the systems, infrastructures, and apparatuses that constitute the ‘totality’ of territorial practices—they are the actors in an ongoing spatial performance.

The environment can be understood as a network of interrelated systems, where each element contributes to an evolving spatial order. Here, Álvaro Domingues’ interpretation of Transgenic Territory becomes an essential reference: ‘the landscape is a work-in-progress combining elementary materials and processes that generate, arrange and encode the complex structures and systems to which they belong’.[14] Every element of the landscape is in tension, constantly shifting between states of stability and transformation. Indeterminacy, in this context, is not an anomaly — it is an inherent condition of space itself. By embracing this perspective, we gain a deeper understanding of territorial dynamics, allowing us to engage with landscapes as open-ended, evolving entities rather than static environments.