OPERATIONS IN THE DARK

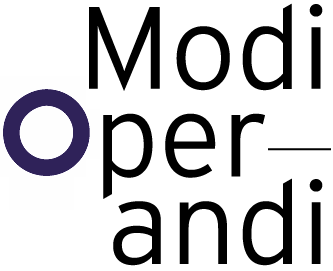

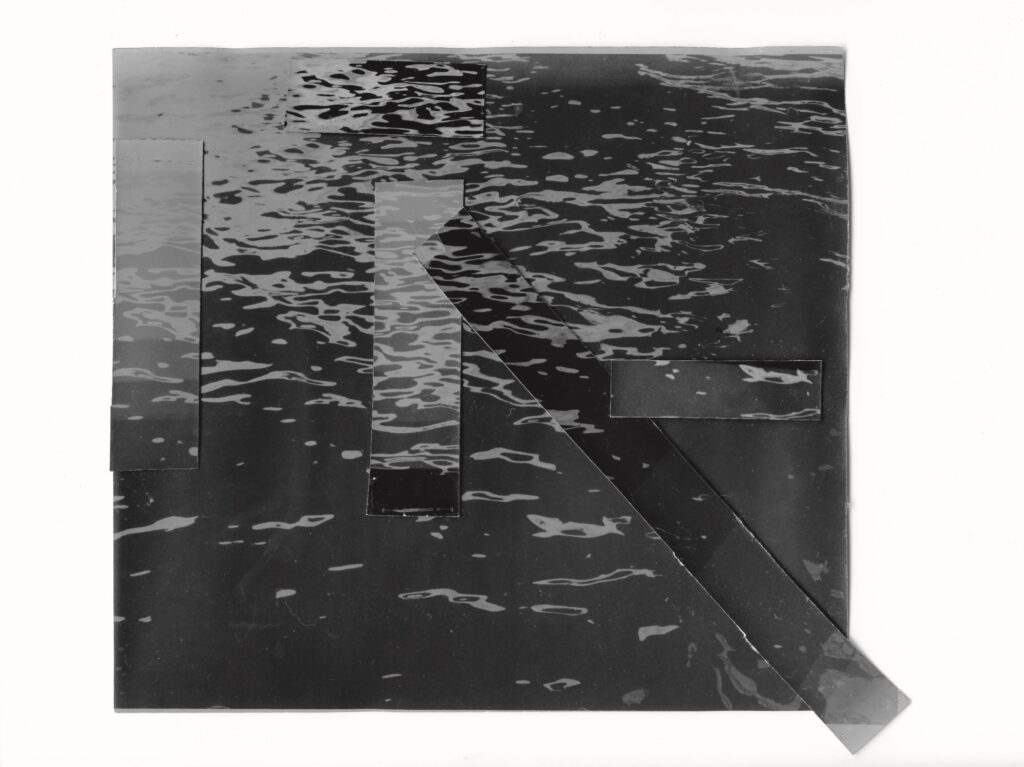

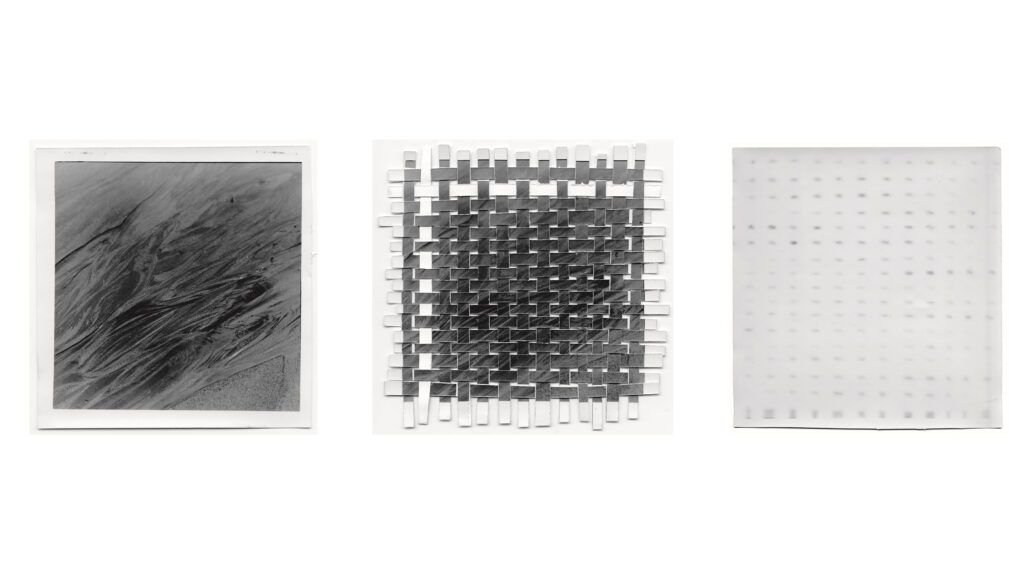

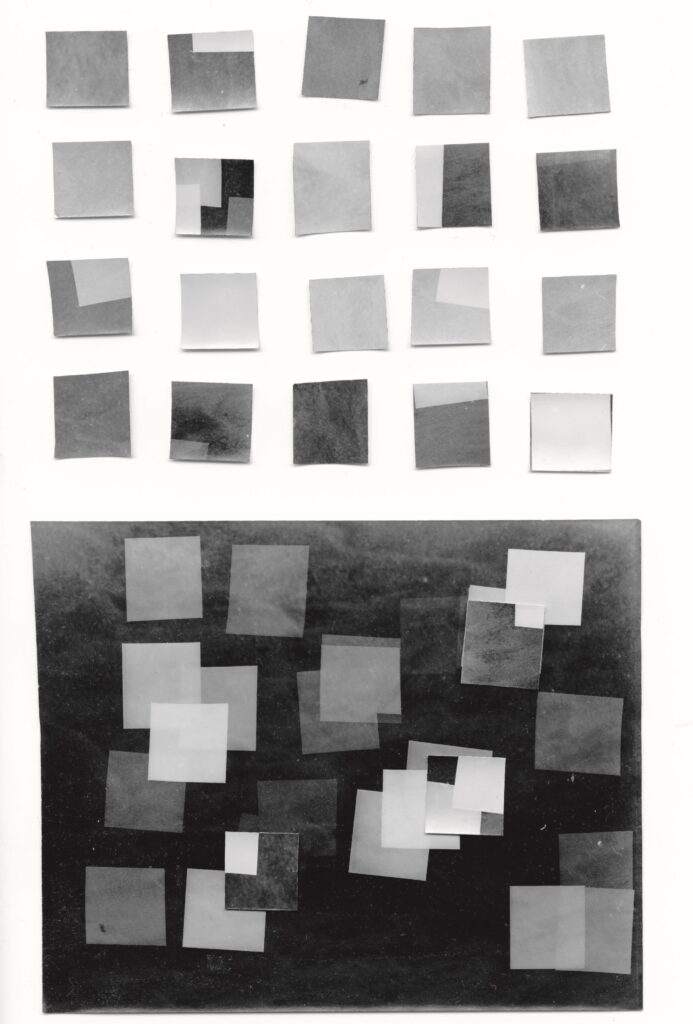

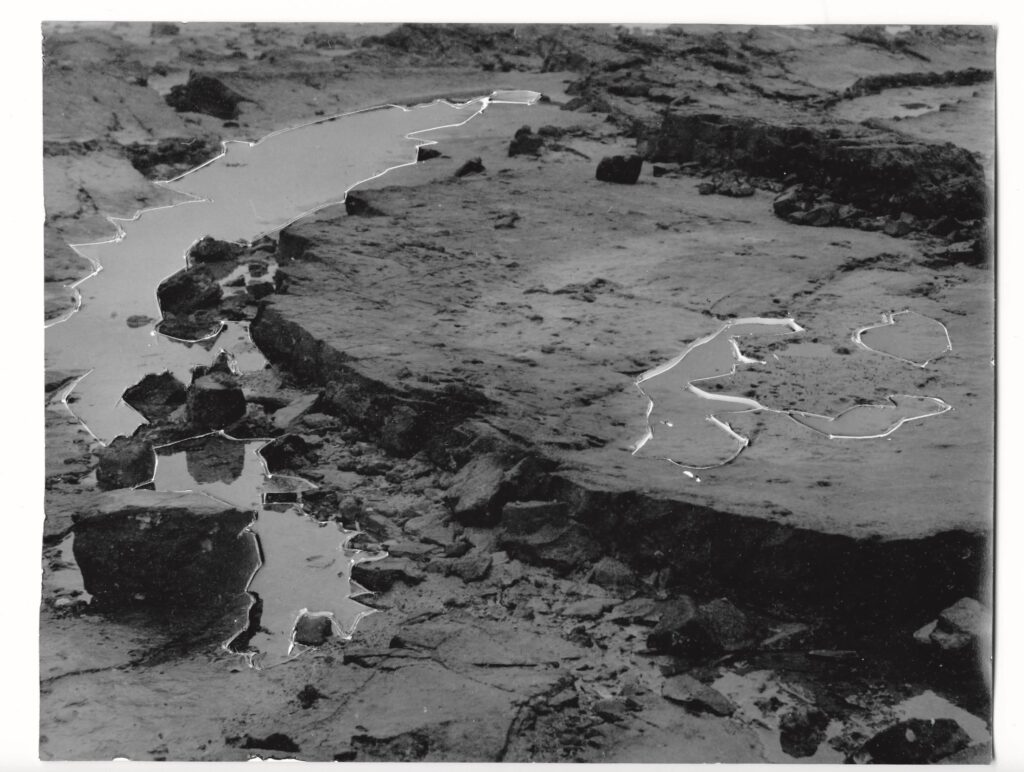

After developing the photographic negatives, the darkroom was used to create prints on silver gelatin photo-sensitive paper. These dark room enlargements were created as a set of photo mappings of the site. A series of operations were carried out in the dark in order to generate new understandings of the site, the image, and their relationship. These photo mappings applied non-conventional print making techniques that necessitated operating on the photo-sensitive paper as a model material before its exposure to the image – this meant working on the paper in the dark, making cuts, rips, and weaves and eventually typing. This enabled a series of errors to emerge, that were consistently more interesting than the actual intention of each work. The error’s compositional strength emerged from a practice that requires incredible control – all light must be eliminated from the room, exposure times are fixed to millisecond increments, photosensitive papers carry different properties that respond differently depending on the negative image itself, developing chemicals are diluted and measured accordingly and held at particular temperature, meanwhile the paper’s exposure to the image is timed and then it goes through a measured procedure of three chemical baths. One sixtieth of a second in Panama at f8 aperture, followed by (in the Netherlands) 9 minutes of developer, rinse, and 5 minutes of fix, and then in the dark again, fifteen point five seconds at f4 aperture and 45cm, three minutes of development, thirty seconds in the stop bath, two minutes of fixer, and the lights come on to reveal an image, or a black piece of paper. As a novice in the darkroom, making mistakes was easy, but too many could cost the work entirely – five hours in the dark room could yield a single image on A6 paper. The minor error, the ‘almost perfect’ emerged as those instances where the truth of the process shone through and yet the control over the system was enough that the intention was clear; of course as a viewer you never know what is accident, and what is compositional choice, and when operating in this logic that line is blurred for the author as well.

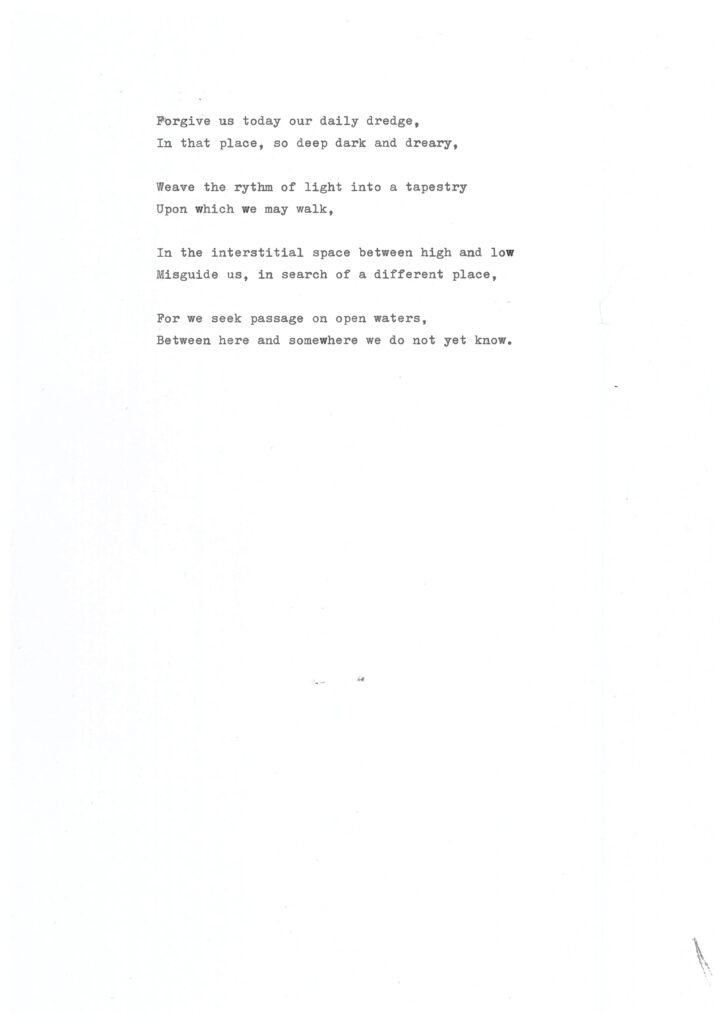

As this series progressed it became clear that there was a distance between the image produced and the site it seemed to represent. My experience of Panama is represented by the frame of the photo and the sixteenth of a second that I was physically there. When compared to the five hours spent with that frame in the dark (at home) it is clear that the experience of the image is distinct from my experience of Panama – and yet they are reliant on each other. There is therefore inherent in the analysis an element of fiction – a Panama imagined retroactively and spoken about within the limits of a clinical (photographic) frame. A challenge to the frame in the context of the pacific waters; an idea that the site is a fiction which I can no longer experience; and operations that were carried out in the dark and relied on projection and light; pulled the project further and further from the safety of shore, and out to sea.

In doing so questions emerged that focused on navigation – how to know where one is going when there is a perfectly flat horizon in 360 degree vision, and how to navigate in the dark? It also required an understanding of technologies of boat building and other floating structures, and pertinently, it caused an investigation into the histories of the global measure.